COP 26: End the Cynicism and Denial – pt 1/2

The global elites call for technology and market “solutions” they know will not reach the necessary targets. They are condemning human society to its demise. A mass movement to demand real solutions is urgently needed. Patrick Bond and Paul Jay discuss the climate crisis on theAnalysis.news.

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to theAnalysis.news. In a few seconds, we’ll be joined by Patrick Bond; we’re going to talk about the upcoming COP26 [2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference] and how technology is going to rush in and save the today or not. Be back in just a second. Please don’t forget the donate button, subscribe button, share button, all the buttons.

Governments and corporations around the world are fully aware of the danger of the climate crisis. They are not lacking information or education; it’s all out there. Yet, as the General Secretary of the United Nations has just said, their leadership is far from what’s needed to avoid hitting one-point-five degrees warming within 15 years and close to three degrees. He said, I think his number was two-point-seven or two-point-nine by the end of the century. And from what I know and from what climate scientists are saying, that’s a very conservative estimation of what’s likely coming. In all likelihood, at the very least, we’re on track to hit two degrees, perhaps as soon as 2050.

When you look at the kind of extreme weather events that take place at two degrees, that should be chilling. No pun intended. Like I said, any relatively informed people know all this, including the political and economic elites. So how can they keep avoiding the reality of the danger? Of course, they might think they’re rich enough not to be so affected, but I think it’s more. They believe that technology will come and save the day and that the phasing out of fossil fuel can wait or be done much more slowly than climate scientists are calling for, or maybe not at all.

The tech they are relying on mostly is carbon capture from the atmosphere and enabling hydrogen production, which is supposed to be clean energy. Well, if it works, I’m all for it. In fact, let’s keep burning coal and whatever. We’ll just wash the greenhouse gases away. The problem is, as far as I can tell, layman reading of what’s out there; there’s just no evidence that this technology works, at least not at the scale needed. Yes, there’s some carbon capture and sequestration that does seem to work, but nowhere near the scale it would take to deal with what’s coming. So are these elites in denial? Or maybe I am.

Now joining us to discuss the upcoming COP26 is Patrick Bond. Patrick is a political economist and a professor at the University of Johannesburg Department of Sociology. He’s not a climate scientist, but as a political economist, one of the best-informed people I know on climate science. He authored The Politics of Climate Justice, based on South Africa’s hosting of the 2011 U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change Summit, and has written extensively on the politics of the climate crisis. And he joins us now from Johannesburg; thanks for joining us, Patrick.

Patrick Bond

Great to be back with the Analysis. Thank you for having me.

Paul Jay

So maybe I’m the one missing it because clearly, the elites are not very alarmed by the situation. Yes, [Joe] Biden had better rhetoric than the Democratic Party administrations have had in the past. And John Kerry is running around saying the kind of things as much as one could hope from a John Kerry. But even if Biden passed his plan without a Joe Manchin throttling his neck. And we got this great image up on the website now of Joe Manchin looking like a professional wrestler with his hands around Biden’s neck.

But that’s almost overstating what the Biden plan was because the Biden plan was very reliant on carbon capture and nuclear-generated, maybe not as much hydrogen in the Biden plan, at least that I read. Anyway, I would assume you agree with me. If it works, if it could be done at a scale, then great long live capitalism. You saved the day. But am I missing something here?

Patrick Bond

Well, just that the associated costs of technology we also have to factor in. And so there are very interesting movements, Indigenous people’s movements, and scientific critics from within the technology community who are asking some very good questions about all of this. Let’s call them false solutions because they’re proposed, along with markets, offsets. Technology and markets are often put together in the sort of same— we call it ecological modernization philosophy, as saviours, as ways to internalize a system’s externalities or to identify the more advanced forms that allow for internal reform of a system.

Now there was one of those that have been tried to make the system work on its own by correcting its imperfections. And that was the ozone hole growing because of chlorofluorocarbons that were coming up. And in Montreal in 1987, that technological fix, which was to ban the old CFCs [Chlorofluorocarbons] and replace them with HCFCs [Hydrochlorofluorocarbons], so that’s for refrigeration.

Paul Jay

So who’s in denial here? Am I in denial of the technology, or they’re just in denial of the whole thing?

Patrick Bond

Well, Paul, the opinion that technology can fix problems is sometimes correct. And when there have been terrible crises like the AIDS [Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome] crisis, we certainly saw our compatriots in South Africa and across the continent, in the south, U.S, and other places turn to technology. To antiretroviral medicines. And we’ve turned to technology for COVID vaccines. So we’re not against technology.

The question is, is it socializable? Can we make it more generalized and give it better access, and does it work? The big question we’ll discuss now, but also, what are the side effects? What are some of the costs to, for example, a green economy that might be based on rare Earth minerals or hydrogen cells that might come from very contested mining sites where Palladium and Rhodium and the Platinum metals group are already subject to intense contestation? Or in the case of highly reflective paint. These come from sands on our coastline in South Africa. Some of the best ilmenite; the titanium dioxide they use in highly reflective paint that we want to paint on top of roofs, maybe on streets to stop heat Islands in the cities.

These also are partly contested in the two major sites in South Africa. Plenty of assassinations, including even the CEO of the local Rio Tinto subsidiary here.

So lots of intense battles going on. As well as big questions as to whether, for example, if you plant an artificial forest, a timber plantation in order to sequester and to draw in carbon. You then set in motion many other ecologically destructive activities. Water will sink. You’ll have a green desert where biodiversity is destroyed. And then, of course, you cut that forest, or it goes down in a forest fire, and all the carbon is released again.

These are some of the, let’s say, false solution aspects of technological fixes. And then you put together technology in the markets. You’ve got an ideology which is called ecological modernization, and it’s to sort of a way to manage by using tech fixes and markets as tools. If you’re a technocrat, you’re in the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, for example, or the United Nations, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. And in many cases, they are endorsing these and funding them without regard to their social impact. Or, let’s say, climate justice.

And that’s where I think there’s a wonderful debate to be had between two very different philosophies. One is just business as usual. Let’s sink some of the carbon that’s up there, find creative ways to sequester it. On the one hand, we can keep going business as usual and make profits out of these 100 trillion-dollar economies. A Canadian, Mark Carney, who is a Bank of England Governor, is really trying to get capitalism to bring in the technology and bring in the markets and the financing to make it all work.

On the one hand and on the other would-be activists who are really pushing for justice. Indigenous people, feminists, the youths. And they’re basically saying cut consumption. Cut these emissions, but partly because of the wealthy in the world, people in the global north, like myself in Johannesburg, we have to address our excessive consumption and the overproduction problem in the world economy. These are the broad terrains of an excellent debate. And regrettably, in Glasgow, we’ll hear the one side, which is silver bullet tech fixes and the magic of the markets.

Paul Jay

Let’s just parse this. So let’s forget climate justice, the justice part for a moment anyway. Let’s forget that mineral extraction comes with certain dangers and the other issues you raised. Let’s say those are collateral damage, necessary collateral damage because organized human society is at stake, so we have to do it anyway. From what I’m reading and getting, not being any kind of scientist in this, at the very best, that if there was a massive, massive investment in carbon capture and sequestration, which I can’t even say properly, it might hit 20% of what’s required, maybe.

Without very serious phasing out of fossil fuel, you can’t deal with the 80%, and maybe that 20% is even unrealistic. But let’s even give them the 20% within the time frame that we’ve got. Am I wrong about this in terms of the justice of the extractive industries or not? It still just won’t work in any kind of urgency we have.

Patrick Bond

Yes, I think the reason it works, and there are some pilots that are being touted in some fossil fuel corporate circles, is that when you can take this carbon, you sequester it, and you store it. Actually, the storage is often to pump more oil and gas out of particular sites where there are residual reserves that need that extra pressure. So we’re already looking at the abuse of the concept. But then again, in a country like South Africa, most of my electricity in this laptop comes from coal-fired power, about 85%.

There is a desperate need to explore this, according to our elites who want to keep the coal-fired power plants running as long as possible, and they haven’t been able to. And the other element to it is that it requires a great deal more energy just to sequester. Up to 20% more energy goes into carbon capture and storage just to scrub and clean the areas that emit CO2[Carbon dioxide] and then find somewhere stable to put it underground. When we’ve seen large concentrations of CO2 underground a Lake in Cameroon, for example, and they come out, they explode.

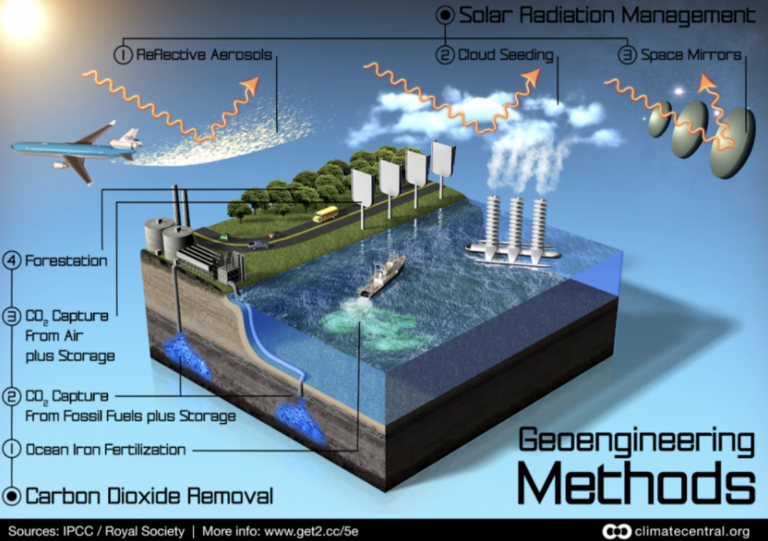

Well, the effects are catastrophic. Several thousand died in that particular incident. I think in a general sense, we’re very unsure about the technology and its safety. And that really goes for a variety of other geoengineering false solutions. The other one that’s being experimented here in South Africa is to go into the area around the Antarctic, just offshore of South Africa, to drop iron filings in the ocean, which would sequester, which would pull down CO2 because it would create algae blooms. And as they sequestered the CO2, they would grow heavier, and they would sink to the bottom. That’s another theory that’s being tested.

Another which we haven’t seen here so much, but it’s been tried in Europe, and a few places, is to put aerosol, often SO2 [Sulfur Dioxide] into the atmosphere as sort of a screen to keep the sun from pounding down as hard as it has in many parts of the world. So a sort of false solution of just putting some sort of umbrella up there. Another one would be the extent to which sequestering plants, CO2, that is, through photosynthesis you draw on the CO2, and the plants create oxygen. Could that be improved by geoengineering?

And so probably the most ambitious and touted of these geoengineering false solutions is to have genetically modified plants that can not just be a few inches but actually a yard deep. And in San Diego, at the Salk Institute, a very talented biologist named Joanne Chory is actually succeeding in some early pilots in getting this CO2 sequestered. But then you’d have to kind of blanket huge chunks of our rural areas to do so. And the question of whether the soil and its nutrients will really react okay on a large scale, but that is another big, dangerous question.

Similarly, with making—

Paul Jay

Why dangerous?

Patrick Bond

Well, it’s dangerous because we just don’t know what the extent of widespread geoengineering is. So we have various United Nations meetings that address this, and they, of course, would take it because of pressure from scientists who are very worried about this kind of Frankenstein or Dr. Strangelove approach. They would take a precautionary principle to avoid these. So there are conventions on biodiversity that have really said we don’t want to see more geoengineering. We just don’t know what will come out of this.

Paul Jay

A lot of people I know that are very serious about the climate issues are very supportive of what I guess is a kind of geoengineering, in a way, except it’s very natural, which is regenerative agriculture and making use of the soil and animal poop and such. Is that not one of the solutions?

Patrick Bond

Oh, absolutely. I would very much go with food sovereignty and agricultural stewardship that is very much outside the current corporate model, which includes a lot of genetic modification that I wouldn’t call geoengineering. I would call that agroecology. Soil scientists have really taught us that the nutrients in the soil are the critical factor. And as we’ve used pesticides and fertilizers, especially fertilizers that are very carbon-intensive. And as we’ve had these factory farms that have been very destructive for animals and for plant life. The potential to do that must be really emphasized, especially food sovereignty, given the injustices in the food system. The need for localized food systems so that we aren’t transporting food these massive distances. There may be one useful aspect of the UNFCCC [[United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change] process.

It’s actually more in the E.U., the U.K., and the U.S. I would call it an imperialist protectionist instinct, and it’s called a carbon border adjustment mechanism, which will look at the carbon intensity of the goods that are coming into, especially the rich Western countries. And what they’ll do is say, well, maybe we should be protecting our industries. And this is one new gimmick climate tax that will essentially allow our sort of Trump-type white working-class voters to say, okay, well, our jobs are being protected, and climate is the reason we’re able to put a tax on a carbon border adjustment mechanism.

The dilemma there is that will hurt third world workers, and the industrialization in the third world will be much slower if these taxes on long-distance or high carbon outputs like we have here become serious. And I think the only justice that would allow that would be that if the climate debt that the Northern countries and the BRICS countries, Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa. Three of those are among the top four of the historic emitters, and what they can do as they put on carbon border adjustment mechanisms as they CBAM other countries.

Well, they should be taking the revenue stream from that and paying their climate debt. And that would be one of the debates about whether we can rejig markets. The UNFCCC isn’t quite there because they’ve been under pressure from big corporates not to mess with, say, a carbon taxation strategy. They would rather be a banker-run carbon taxing or trading scheme. The emissions trading of Europe, of California, parts of Canada, and now in China and a few other places, and at best, a carbon tax that is not particularly creative, the kind that got in 2018 [Emmanuel] Macron, and in 2019, [Lenín] Moreno in Ecuador into such trouble with the French Yellow Vests and the Ecuadorian uprisings. That kind of carbon tax, which is often reactionary, is something we should definitely avoid.

But I think creative taxing to address how much carbon is involved in trade, long-distance shipping, air transport and then try to price that in. That would be one of the useful ways, and I would say ecological modernization techniques like technology that we could socialize with could play a role. But climate justice is still going to be critical. We can’t sort of leave it because it is really an important question. Where do we get the lithium that Elon Musk, the richest man in the world from here in Johannesburg and with his Tesla and his attempt to have big batteries, well, he’s really digging in? He endorsed the coup in Bolivia in 2019, and that’s the kind of, let’s say, external damage that goes with tech fixes that we have to address. The green hydrogen with the platinum and group metals here will be hotly contested and the ilmenite.

And I think all over the world, we’re learning about the dangers of a green economy that has new kinds of extractivism hardwired into it, where there will be resistance and contradictions and very serious socio-ecological and economic costs.

Paul Jay

So if you take carbon capture as one piece of it and it seems to be the major piece of what the Bidens of this world are imagining, and the science does not seem to support it as a solution, at least as I say, within the time frame needed. Then let’s get to hydrogen. Is hydrogen a real alternative, even if it requires some controversial, dirty, damaging extraction? But even that, is it possible on a scale, and let me say, is it possible to produce it with sustainable energy on a scale needed? Because even if it’s effective switching to hydrogen, is it really possible to produce it in a clean way within a timeframe that’s needed?

Patrick Bond

This is the challenge. For example, Sasol, which is a former state-owned company that was set up during apartheid to try to avoid the sanctions on oil against the racist government in South Africa. And so Sasol is host to the number one point source of CO2 emissions in the world, a city called Secunda, where they squeeze coal and gas to make liquid petroleum. And now they’re trying to be green, and they’ve moved a lot of their assets offshore to the U.S. as they privatize to Lake Charles, wherein Louisiana, they’re a big part of Cancer Alley with a big cracker.

But I think the main thing about them, they’ve come back now and said, we want to be green. And their CEO, Fleetwood Grobler, has said we’ll put huge solar facilities with concentrated solar and create this hydrogen reaction using our local inputs for the hydrogen cells, the platinum group metals. And so that raises a couple of questions. Well, where would they want to pilot them? Do these work? And the answer is for trucking and buses. So for some of the heavy transport sector activities where ideally, we would really have moved a lot of this road-based, especially trucking of containers from the highways onto the rail system and use solar and wind to power trains, that would be ideal.

But as a second-best, I think putting hydrogen cells into our buses and into our trucks would be an interesting pilot. And then you ask, can it be done on a wide scale? And then, as I just did, question whether a private company really is the right way to experiment and to bring things to scale. Their agenda, to get about a 30% profit rate in hard currency. It’s going to require a great deal of squeezing our facilities here to get that kind of profit rate that their investors demand.

But more importantly, what is their record? They are, I think, trying to pretend they’re going green because this is part of the so-called net-zero strategy of Sasol and many other big fossil fuel companies and other industrial companies that want to say we will find some technological solution and markets through offsetting and emissions trade, to pretend that our net by 2050 is actually zero. And that’s where a great deal of climate justice watchdogging and good scientific watchdogging are going on. To ask, we really don’t need any emissions. And the net-zero is really not zero. And we really need a genuine commitment to zero emissions.

If you look, for example, at the way China is beginning to roll this out, you’ll often find with their centralized companies their centralized policymaking, they can do it more quickly and at scale, of course. And I just haven’t seen that happening in an impressive way. For example, in the way that they began to make that big switch to solar and to wind. So I’m a little bit skeptical, knowing this company a bit too well to trust anything that comes out of their CEO’s mouth.

Paul Jay

So as you said right at the beginning, it’s not like you or I are against technological solutions; actually, far from it. I think it would be wonderful if there was a technological solution. I know back during the [George W.] Bush administration, there was talk about going to the moon and getting hydrogen, and if they could do that, well, then wonderful. It’s a clean way to get it and problem solved. Although, they seem to have stopped talking about that. I haven’t heard this thesis recently. But the bottom line here is even if and it’s an enormous if, I’ll say it again, maybe this technology deals with 15%, 20%.

And that’s being, I think, from what I know, wildly optimistic that it could actually deal with 15% or 20% of the problem. But whatever the geoengineering piece of this is, and at least from what I know, I don’t rule out all possible geoengineering solutions, which I know some of my friends do. But I certainly am in favour of investigating, spending some money looking. And some of the climate scientists who I think are quite real leaders of the field in terms of the IPCC[Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] reports and who have said that we are on track to hit two degrees by 2050.

They also say there will have to be a geoengineering component of the solution. But whether you agree on that or don’t agree on that, all the scientists I know of say you got to phase out fossil fuel, and you got to do it urgently. And that’s not happening. And as I said in the beginning, the elites know all this. We’re not saying anything that’s informing anyone who wants to be informed doesn’t already know.

So what’s going on in their heads. And it seems to me what’s going on in their heads is what the economist, I believe his name is [William] Nordhaus said, and he won a Nobel Prize. He says that it’s okay to stabilize temperatures by the end of this century at four degrees. They believe, they the rich, the elites of the world, can live in a world of four degrees. And if the peoples of the Southern Hemisphere get fucked, excuse me, well, there already are. So what’re some more poor people in the Southern hemisphere. The rich don’t care about poor people in the Southern hemisphere now. Why should they care more about them at the end of the century?

And I think in terms of the message that people need to get, it’s not a lack of information here. It’s not that the elites need to be educated, and it’s not every member of the elites, too. I would say there are some that actually do get the problem and have some level of social consciousness, but the majority, it’s a straight calculation. Me, my kids, my family, my wealth will do okay in a world of four degrees. And that gives us time to sort out the technology. Am I wrong here?

Patrick Bond

No, you’re right. And we’ve seen some very disturbing instances of a sort of strategy of personal insulation and greed. We’ve seen it with the vaccine imperialism, in which, say, the Canadians ordered five times the number of citizens, whereas Africa is still about 4% vaccinated. The desire to hold on to the intellectual property rights that Angela Merkel, the former German Chancellor, and Boris Johnson have shown absolute dogmatism in the World Trade Organization in those negotiations. Or the way in which the rich got super-rich during COVID and all of our efforts to promote a build back better, a more rational and perhaps nationalized system of health financing or health care or mutual aid systems or subsidies to ensure that people had good work.

Aside from a few countries where movements were at least strong enough to get some of those gains, mostly, this kind of story is the Elon Musk’s and the Jeff Bezos’ soar in their wealth and their ability to insulate and to do as you say, to think only of themselves, to go to the moon, maybe they want a planet B if they think that’s possible. But I think the big dilemma is will we get our movements to work together? And one of the critical things is that the capitalists have told their workers that the climate crisis is going to be a crisis for them because of the transition to the decarbonized systems of energy and transport, agriculture, production systems, disposal, even consumption, those will be adverse for workers.

And we obviously need to say to workers, there can be a different way about it. We can make a job-rich, just transition in which subsidized jobs and care jobs, the mutual aid feeds into caring for the planet, not just for our families and our communities. And I think that’s the critical thing left out of the UNFCCC because it’s such a topdown process and hasn’t involved particularly strong inputs from the labour movement. Likewise, the other areas of social injustices against Indigenous people that we’ve been seeing and say in the U.S. and all over Latin America than fighting back against major extractor systems or pipelines.

The youth, especially the next generations who said to our generation, you’re really treating us with total disrespect, which is absolutely true. As you said, it’s really about the ability of the particularly high emissions group, which is the world’s top 10% and particularly the top 0.1% who are private jetting it around. They really are not thinking about future generations, are they? Gender is another critical area, along with race North-South, in which the United Nations has been extremely weak, maybe giving some tokenistic support. But it’s where the C.J. [Climate Justice] movement for many years since the late 1990s has come up and said, we are the constituencies who have indigenous solutions to problems who don’t want to be on a Western materialist mode of consumption. That is part of the problem behind the high levels of per capita consumption in the north.

We want to actually have a different way of doing things, and that voice has been very limited because of the power. Often it is said that the three dirty words in the UNFCCC, which put a block on anything to do with justice. Those three words are the United States Senate because it means that anything that we try to get codified by the biggest historic emitter will be vetoed by, if it’s 50 or 52, depending on West Virginia or Arizona Senator, whatever that ratio is, it just means that the likes of John Kerry or Joe Biden, long term U.S. Senators don’t have either the courage or the political will to push it through.

And I think at the level of the base in society, we haven’t got enough social shaming of those U.S. Senators and of the elites more generally in these countries, including South Africa. And that’s what our job is. And one of the dilemmas is whether the UNFCCC will continue to retain any credibility and provide any hope for the rest of the world to say, well, aren’t the elites going to do something at least in Glasgow? Would they do it in Cairo next year and a little resort near Cairo for the COP27?

These are questions which I think Greta Thunberg has given the very best answer to last month, which is blah, blah, blah. This is really all we’re getting, or that James Hansen, the great climate scientist. When he was asked about the Paris Climate Accord, he said one word, a scientific assessment; it’s bullshit. He used two others: a fraud, a fake. And I think that delegitimization of what the elites are doing with their excessive hopes in technology. By the way, they’re not talking that much about markets, and the obvious reason is that the markets are rewarding, the oil and the gas and the coal, and it’ll get even worse as the winter sets in in the north, with the prices skyrocketing here in South Africa, as we try to stop coal mines, the export price went from $40, $38 I think at the very bottom in April 2020, up to $230 recently.

So we’re really looking at the return of coal. That’s really the danger, which is capitalism is in no way setting itself up to solve the problem. It’s making it worse by incentivizing yet more fossil fuel extraction. And I think that’s the dilemma. Whether the elites will continue this tech fix fantasy and market strategies, which are already haywire and carbon markets depend upon financial markets, which depend upon quantitative easing to bubble up financial assets way beyond their real value so that we could have a crash the way we did in the European Union emissions trading scheme in July 2008 from €35 down to ultimately €8, and then down to €3, and then in April 2020, similar crashes that correspond very closely to bubbles in the world financial system.

And we’ve certainly got the worst bubble in world history still building now with quantitative easing. And that means, I think, Paul, one of the questions are climate justice forces around the world in their blockadia modes in different micro settings, with the youth with extinction rebellion, very militant, sort of direct action against the elites. We’re all asking, will Glasgow be a site where those of us who are critical of these elites will get more momentum or like after Paris, will they scam the world into saying, oh, well, now the deal is going to work, and I think that’s our big question for the next couple of weeks as Glasgow takes off.

Paul Jay

I think one of the things that have to be done is that there needs to be a massive mobilization à la the civil rights movement, but especially in the States where Republicans are strong, where a lot of fossil fuel is based. And I don’t mean primarily a bunch of urban white kids need to go to pro-Trump States, because in every one of these pro-Trump States, there are a lot of people who are already organizing, who get the climate question, who are ready and willing and try their best to talk to their neighbours.

And they are organizing there. But they don’t have resources. And the Democratic Party, they look at a congressional district or any race, and they say, can we win it or not? And if they don’t think they can win it, they don’t give a damn what happens in that race. So they don’t fund the candidate. They don’t do anything to help fund organizing in between elections. If there are any funders out there, whether they’re foundations or others, get focused on funding the progressive climate activists who already live in these States, who can talk to their neighbours and who can really organize and help people get trained on how to organize and combine that with the messaging of what a just transition looks like.

I keep saying over and over again in these climate interviews I’m doing, it’s not beyond me because I get why Biden isn’t focusing on just transition, but it’s a crime that they’re not. Because if you combine resources for organizing and running in elections in these pro-Trump fossil fuel States, anywhere from Texas to Pennsylvania, you name it, combine that with the promise that no fossil fuel worker directly or even people who indirectly earned their income through fossil fuel will lose income; they’ll get subsidized.

You combine that messaging with that kind of local organizing. It could help, I think, change the politics to a large extent of some of these States. And I know there’s all kinds of cultural issues, but I was on a plane recently flying from— I was interviewing Daniel Ellsberg, and I was flying afterwards from Berkeley to L.A. And I’m sitting next to this guy who, it turns out, is an anti-vaxxer, and I’m sitting right next to him. But anyway, he’s very pro-Trump on everything but climate. He says, no, I do get climate. He lives in California. He sees what the heck’s happening. And I actually think the climate issue may be a very vulnerable piece within the psychology and identity of the pro-Trump forces. So I think this is something that’s really got to be in the mix of the planning and conversation, which has to be done really urgently.

Patrick Bond

I think you’re right, and if we can look at, say, California, where Gavin Newsom felt a little bit of pressure, but not yet enough because, of course, his opponent was to the right in the recall election. But the kind of pressure that the forest fires, the droughts, the terrible conditions in California represent while [Gavin Christopher] Newsom continued to issue offshore licenses. And this is the great irony that even in what would ostensibly be the most advanced and progressive state for doing just transitions and subsidies for solar and wind, you still have an addiction by some of the power elite there to the traditional fossil fuel sectors, which have especially funded Trump, but also the Democrats.

And I think that might be why this electoral terrain is very difficult to work this issue, and we’re going to have to keep being in the streets. But being with pilots that will show workers all around these deindustrializing and sort of McJob type sites like West Virginia, that you can go from coal mining into something that’s just as much more creative and healthy, restoring the pipelines of Louisiana into something that instead of spewing carbon would be something that could be a removal process. All sorts of options exist in South Africa.

A million Climate Jobs booklet has been circulating for more than ten years to try to work, say, metal workers to get their heads around, not just producing high carbon luxury automobiles for the export market, but public transport or to move away from smelting and into something much more creative with their skill set in industrial sites. So these are some of the big challenges. And if we don’t do that to have community labour, gender, Indigenous and especially youth coming together with an environmental program, then it’s our fault.

It has happened. Major changes occurred. And I think the social shaming that, for example, went with Black lives Matter on Confederate statues in cities like Richmond, Virginia, meant a dramatic change occurred in consciousness and in politics. And that gives me hope, as did the change in the 1980s about companies making profits here in apartheid South Africa. Suddenly divestment came up. So it’s encouraging. For example, Paul, even a Harvard University endowment fund, was able to make that divestment decision very recently with enough pressure from the enlightened bourgeoisie of the United States.

So that’s social shaming. Fourteen trillion dollars of funds are now divested from fossil fuels. It’s moving. But yes, we need to make it move much faster. And I think again, the question coming out of the Glasgow meeting is, do the elites have any purchase on saying, leave it to us. We’ve got a strategy, or must we pick up the baton and really move with a much greater force against these leaks? I think it’s going to be more of the latter because I don’t see any way that the major challenges in Glasgow, which include, by the way, forcing companies to leave their fossil fuel underground and declare them unburnable carbon stranded assets and to deal with climate finance, not for profiteering by the likes of the Mark Carneys, who just want to blend public and private finance and make a high rate of return when the interest rates in the U.S. may be coming up, but they’re still too low for his financial friends.

And I think that’ll be the big terrain of struggle here, whether the south gets to, but the point which was typically ignored, that climate reparations are due and that the climate financing gimmicky the $100 billion a year Hillary Clinton promised really isn’t acceptable in its current form, high priced loans or conditions or ways that the private sector can get in and make these kinds of venture capital type profits.

Paul Jay

So we’re going to keep talking with Patrick in part two. So, for now, this is the end of part one. Please don’t forget to donate and subscribe and sign up on the email list, and we’ll be publishing part two the next day or two after we publish this, which will all be almost right away. Thanks for joining us, Patrick.

Patrick Bond

Thank you.

Paul Jay

Thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news.

END

I would like to suggest a guest for the Analysis: William Rees, who has a video on Youtube lecture titled The Enigma of Climate Inaction – On the Human Nature of Policy Failure. William Rees is a Canadian population ecologist and developer of the “ecological footprint”. I recently discovered him, and I’m impressed with his wide knowledge on the core issues associated with environmental degradation.

I’ve been kind of avoiding coverage of COP26 about as much I have been in past years as I have not really noticed much difference between previous COPs.

The thing I noted this year is that a child that was born during COP1 (1995) is now 26 years old. Imagine all the world-shaping things that have happened in the last 26 years.

As an example, Jeff Bezos started Amazon in a garage about 10 months before COP 1 in Berlin. Google showed up three years later. Also to remind that the WTO officially commenced operations in Jan. 1995. There’s probably a Charlie Brown football image in there somewhere.

Not trying to be a total downer – there’s really a lot of good stuff in those 26 years, just the COP process has maybe not been as productive as it presents itself?