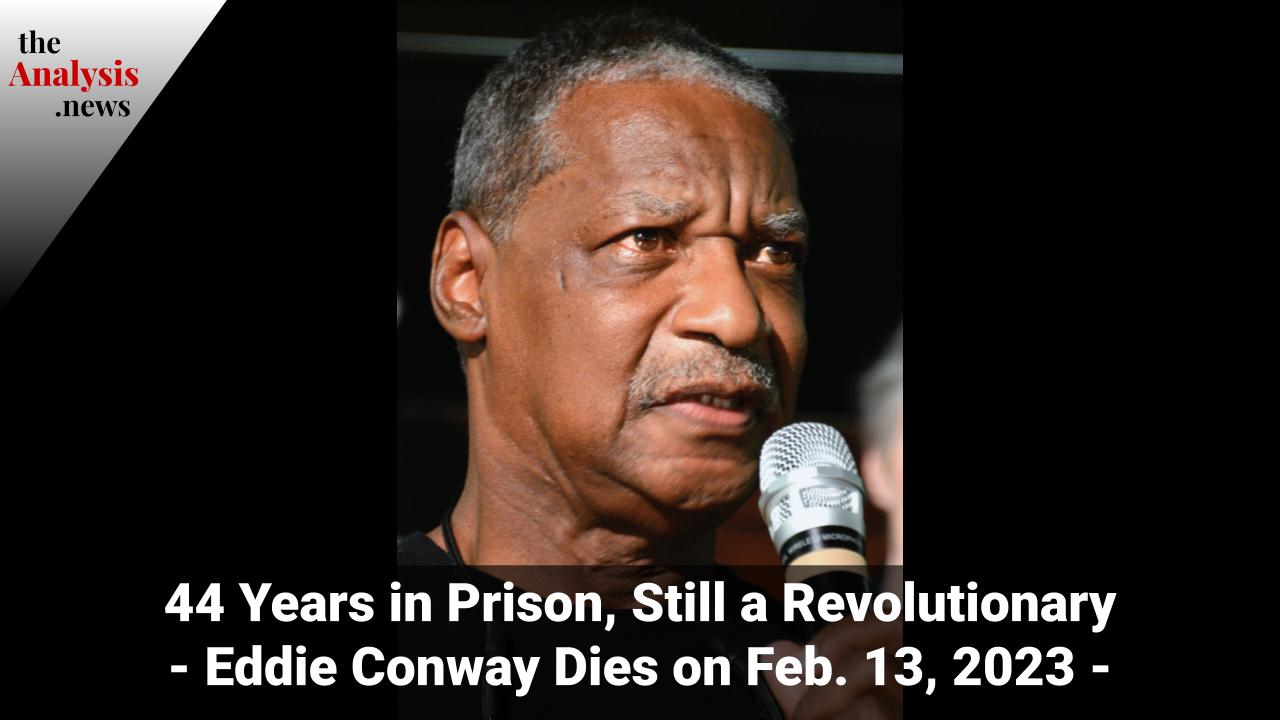

44 Years in Prison, Still a Revolutionary – Eddie Conway Dies on Feb. 13, 2023

Eddie Conway, a fearless fighter for working people everywhere, died on February 13th. Eddie was a Black Panther who was unjustly imprisoned for 44 years. In his honor we republish a series of biographical interviews hosted by Paul Jay, first released in 2015.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. Eddie Conway was lieutenant of security for the Black Panther Party from 1968 to mid 1970.

…

Incarcerated in 1970, Eddie served nearly 44 years in prison after being convicted of shooting at two police officers. (One, Officer Donald Sager, died.) He was released six months ago today.

…

He declared his innocence ever since his arrest and points to the absence of any direct evidence, his inability to secure a legal defense of his choice during his trial, and the extent to which a jailhouse informant–I should say, a notorious jailhouse informant’s testimony was relied on by the prosecution for his conviction. While incarcerated, he earned three college degrees, organized a literacy program, and ran an education and conflict resolution group for gang members, although–to use word Eddie’s words, street organizations. He continues now in Baltimore to work as an activist, and we’re pleased and privileged to have him here in the studio.

Thanks very much for joining us.

EDDIE CONWAY, FMR. BLACK PANTHER PARTY MEMBER, BALTIMORE CHAPTER:

Thanks for having me.

…

JAY: And we’re pleased and honored to have you here in the studio.

CONWAY: Thanks for having me here.

JAY: So I should have said as well you are the author of a book. It’s called–I have it here–it’s Marshall Law: The Life & Times of a Baltimore Black Panther.

…

I feel like we could do about 15 segments of interviews here, your history is so rich and it’s such an important learning experience for people that are trying to change the world today. I didn’t, in your introduction, say that you were a revolutionary, and as far as I can make out, you still are. You’re someone that wanted transformational change, and, to use your words, you put your body on the line to do it. But what struck me most in reading your book–and I’ll tell everyone honestly, I have read most of the book, but not all of it–but the theme that I think comes out most strongly for me is the fight to maintain your humanity. And it wasn’t just a fight in prison. It’s a fight that happens out in the community as well. I guess it’s a more intense fight in prison. But the force of this society’s culture, this politics, economics, it’s very dehumanizing.

Your book begins with your childhood experiences and becoming aware of the extent of systemic racism and white supremacy. Talk about some of your early events that formed the way you came to look at the world.

CONWAY: Well, I think probably the initial thing that happened was when I was in the fourth grade. I attended a school on Mount and Riggs street. A hundred and thirty-two it was named. And we put on a play for Christmas, and we didn’t have an auditorium, and we were allowed to go across into the white community to their elementary school to use their auditorium, so that our family members could come and see us act in the Christmas play.

JAY: This would be about 1954 or ’55?

CONWAY: Yes, somewhere around there. Huge school. It was impossible–you could have set almost our whole school into their auditorium. And, I mean, the science lab, outside track, swimming pool–I mean, it was devastating for, like, a little eight-year-old.

After that, coming back into the black community and going back to that school, it damaged us so much we acted out that whole year. In fact, I failed the fourth grade as a result of that experience. I think that was my first contact with institutional racism in Baltimore.

JAY: You grew up initially in a community that was mostly black, but then you moved to a community in downtown Baltimore, but it was still mostly white.

CONWAY: Yes.

JAY: And then you start to see white people started to leave.

CONWAY: Yeah. Yeah. As a matter of fact, that experience was kind of extended to us moving to East Baltimore. We moved to East Baltimore, up around Preston and Milton Avenue, and there was very few black families in the community at the time. And within six or eight months, white families were fleeing the community right and left. It basically became an integrated community, and then, eventually, an all-black community.

And the encounters that we had during that period was, like, really negative and hostile, people not wanting us in the community. And it was–obviously, that was a more adult-like experience, because I was at that time a teenager, and we still had the segregation and racism in the city.

…

JAY: Here’s a quote from Eddie’s book about that period.

Baltimore is south of the Mason-Dixon line, and in 2011 is probably more Southern than Mississippi in 1962 in terms of segregation. But there was always the safety of numbers back then. Up until my early teens, my parents kept me away from those places where black and white intersect and sometimes conflict. My parents tried to hide the reality of second-class citizenship, so they never talked about the violence of the South, beatings and lynchings. So I was forced to figure out some things myself. And by that time we were living among whites, and now they were the minority.

As you become a teenager, you write in the book of getting involved with some of the activity of young people, which was striking out in anger against those conditions. What kind of stuff?

CONWAY: We obviously–at that age we there were no gangs, but there were groups of guys that would hang together. It wasn’t an, officially, gang. So you might want to call them crews or something like that, or just neighborhood gatherings. And we would come in contact with other neighborhood gatherings that–they weren’t gangs. That West Side Story thing is bogus, probably, right? But there were conflicts at the edge and the borders of our communities between us and them around the use of the baseball fields.

JAY: This is black and white.

CONWAY: Black and white–around the use of the baseball fields or football fields, etc., even to the point–and it’s probably not good to say this, but even to the point of young black people taken away material things from young white people as they passed.

JAY: Like bicycles and so on.

CONWAY: Bicycles, bats, gloves, skates, radios, things that they brought through our community that we didn’t have. And I guess we kind of had an understanding that those things should have been things that we should have had and didn’t have for whatever reason, and, to a great degree, that probably white people were responsible for that. And so we did take those things back through force, violence, interaction, etc.

JAY: So this idea that there’s something fundamentally unjust growing up black in Baltimore, by the time you’re a teenager, that’s clear to you? I mean, and clear to you not just in sort of a–in a somewhat political way.

CONWAY: It’s clear–I don’t think we understood the politics. We understood the oppression. We understood that we were treated differently in our community. Friday, Saturday, Sunday nights, the enforcement agencies in our community treated us differently. They didn’t bring us home. I mean, it wasn’t a case of officer-friendly. It was always a case of either putting us in the trunk of a car, or taking us somewhere and hitting us upside of the head, or just intimidating us. So we knew that and we knew what the general presentation was, that these are your friends, these are people that are supposed to look out and serve and take care of you, and that wasn’t our reality in our community. So we knew there was something there. But we also knew that anytime we ventured outside of our community, we had negative encounters, either with other community people or law enforcement, etc. So we knew that there was something seriously wrong there, even when we went downtown, say, for instance.

JAY: Your father, if I remember correctly from the book, worked for the city?

CONWAY: Yes.

JAY: And your mother worked?

CONWAY: No, actually, she didn’t.

JAY: She didn’t.

CONWAY: Yeah.

JAY: But you’ve got a stable income.

CONWAY: Yeah.

JAY: And you write that you were poor, but you never wanted for food and basics. But what were the politics? What was the conversation at home about why things were the way they were?

CONWAY: Well, I don’t think we–and I’m speaking now as a young teenager discovering girls, hanging out, partying, running in the streets. I don’t even think I paid too much attention to the conversations that were taking place in the house. And I’m pretty sure there was, like, hostility, and I’m pretty sure there was some anti-white kind of attitudes that would take place in the house among the adults. At some point, I think, probably not then, but earlier, I think we had lost some uncle in Korea and there was not any compensation for his loss. The family was devastated by that. So there was always some things going on in the background. But there was a party Friday night or there was a party Saturday night, or we wanted to go and hang out in the movies or something. So I didn’t really have an interest in that stuff and missed most of it quite honestly.

JAY: So we’re talking into the late ’50s and then the very early ’60s. Baltimore didn’t look the way it looks now. I mean, I heard you talking to a mutual friend of ours, Marc Steiner, what it was like when you got out of prison and actually saw rows and rows and rows of boarded-up housing. And some people call these–some of the communities look like they’d been war zones or something. But that isn’t what–growing up here, that wasn’t what it was like.

CONWAY: Yeah, communities were actually intact. There were people throughout the community from different class levels–middle class, working class, even some close to upper-class people lived in the community. You had doctors, you had lawyers, you had garbage men, you had street hustlers, you had teachers, you just had regular people going to work at Sparrow’s Point, and they were all mixed in in a space in the community, including the person that might own the store down the street or the person that owned the bar. You know, up the street there might be a Cadillac, down the street there might be a Volkswagen.

But there was never any abandoned houses. I mean, there might occasionally be a vacant house where somebody’s moved out, and somebody might move in there in a week’s time. So seeing the city with the houses boarded up, some of the houses decaying and collapsing, empty lots, all of that’s shocking to me, because I’ve never seen any place that look like that.

JAY: Yeah, just to remind everybody–

CONWAY: I mean, it’s a city of decay.

JAY: –Eddie was in jail for 44 years, so he hadn’t seen the city for all of that time.

CONWAY: Yeah.

JAY: By the time you’re getting to be 15, 16, are you angry at the injustice of it?

CONWAY: I’m not sure consciously that–I mean, I knew there was injustice, but at the same time, I guess my desire was, to be honest, to have fun, to party, to enjoy life, and to try to see if I could find a way to make a life for myself. So I was looking forward to becoming independent, looking forward to becoming self-sufficient.

JAY: But you’re getting involved in some kind of nutty stuff.

CONWAY: I’m getting involved in all kinds of nutty stuff. But I’m not getting involved in nutty stuff because–one of the things is I dropped out of school. I dropped out of school at 16. I was already working then, and I was guess I was operating under the illusion that I was doing well. I had a job, I had been working since I was 13, so by the time of 16, I was pretty secure in the sense that I could get the stuff that I wanted to get, I could buy the things that I wanted to buy, and I made a decision not to go back to school. I was really having fun. And my mother confronted me and basically–.

JAY: “Fun” means partying and–.

CONWAY: Yeah, fun, partying, enjoying hanging out, etc. And my mother confronted me and basically said, like, if you’re going to live here, you’ve got to go to school, you’re going to have to finish school. And I’m like, okay, well, I got a job. I don’t have to live there. I’m moving out.

And so at 16 I moved out, and I moved into a living arrangement in which we had a three-story house, and it was about six of us. And right away I discovered that all of the fun that I was having had something to do with Mom and Pop paying the rent and them buying food and them paying for the electricity. I didn’t realize all of that stuff had to happen. And I couldn’t stay up [till] three o’clock hanging out with my buddies and partying, even though we had a house, we had a three-story house, and it was, like, wild parties in there all the time. I had to be in the bed at ten o’clock because I had to get up at five or six o’clock in the morning and go to work, because you can’t keep a job if you’re partying all night. So I had discovered the hard way that all the partying and all that stuff was–kind of, like, had to go on the back burner and it had to be kind of like a weekend warrior with that and I had to take care of myself. But a lot of my friends continued to do wild stuff.

JAY: Yeah. In the book you write about one of the guys getting involved in a fight with some New York drug dealers and some shooting takes place.

CONWAY: Yeah. And that stuff eventually continued to happen to the point where I realized that, well, okay, I need to–people were going to jail. The house was being raided. Things were happening. And to me it was like, okay, I can’t continue along this path, because if I do, I’ll end up in jail.

JAY: Right.

CONWAY: Yeah.

JAY: Are you at this point in your life conscious, at a conscious level, of this idea of systemic racism, white supremacy, that there’s something basically unjust the way African Americans are dealt with in America?

CONWAY: No, I was completely apolitical, apathetic, didn’t give a darn, for use of a better word. I didn’t actually care. I was still enjoying life. I was still doing stuff. I mean, I knew, I was fully aware that there was problems. The civil rights movement was in its heyday or better. The civil rights bills were coming up.

JAY: [crosstalk] we’re now into the early ’60s [crosstalk]

CONWAY: Yeah, we’re in the early ’60s, so, you know, the March on Washington, I mean, all of that stuff was taking place. There was radical talk going around from Malcolm X, etc. You know.

JAY: So it’s in the air, but–.

CONWAY: It’s in the air, but we’re having a wonderful time in this house.

JAY: But you decide things are getting out of control, the house, and you’d better do something, and you join the U.S. Army.

CONWAY: Yes, and I decided that it was time for me to relocate. Yes.

JAY: Here’s another quote from in Eddie’s book. And by the way, this book’s available in all the normal places people buy books.

I was ready to serve the nation, Eddie writes. There was no place I would not have gone, nothing I would not have done at that point for the good old U.S. of A.

What did it mean to be American to you? What was Americanism?

CONWAY: Well, at the time I thought that we all had the opportunity to advance, to move forward, to make progress. I kind of felt like, okay, well, maybe I dropped the ball dropping out and partying, etc. Maybe I could pick the ball back up, reengage.

JAY: You write that you still believed the American dream.

CONWAY: I still believed that the American dream was possible.

JAY: For black people.

CONWAY: For black people. For all people, in fact. And I just–I really–I guess, looking back, hindsight now, I guess I really thought that whatever wasn’t happening correctly was my fault. You know. I blamed the victim, so to speak. It was like, okay, well, I’m just not putting forth enough; I’m not going–I should’ve went to college, I should have did this or I should have did that; given a better effort, I could do better, and I can make it, I can survive. And toward that end, I think, I looked at the American dream as the reality that would change the world.

JAY: So that starts change for you, and I think in the next segment–.

…

So that dream started to shatter for you when you were in the Army. What happened?

CONWAY: Well, I think initially one–being gung ho–because I was when I went in the Army, I was gung ho. I–.

JAY: And you joined the Army in ’64?

CONWAY: Yeah, I joined the Army in ’64, and I went through the training, I went through the advanced training. And I end up in Europe and I end up as a medic.

JAY: In Germany.

CONWAY: In Germany. And they put me in a unit, and there was 25 people in the unit. There were three black guys and 22 white guys. And one of the black guys was a sergeant, and one of the black guys were a private. And, of course, I was a private myself, right? And the first thing I realized was that there was just a tremendous–and for the first two weeks–tremendous amount of racism in the Army. Every single day, the two people that were selected to go on KP–that’s duty–or to dig ditches or to pick up garbage were the two black guys, me and the other guy. And it happened every day for, like, two weeks. And at some point it stuck to my craw, so to speak. And the one morning they came out and they said, like, we need two people from each platoon. And as they were going up the list getting the black guys from each platoon, before they got to my platoon, I yelled out in the rank, which is, like, a no-no, “Let Conway do it.” You know? Because I knew they was going to pick me anyway. They’d been picking me for two solid weeks, you know? And so it shocked the whole formation, because, like, soldiers don’t do this. You know, you stand there, you’re at attention, and you keep quiet, they give you an order, you go do it. You know. So I’m, like, rebelling right there.

So, in fact what they did was they took me to the company commander’s office and said, well, why did you do that? Why are you doing that? And so I explained and I said, look, I’ve been here for two weeks, and every single day–there was 25 of us–every single day, only the two black guys get picked; none of the white guys have been picked I’ve been here. What kind of fair deal is that? And it was from that point there that, one, they started leaving me alone, but, two, I started looking at the environment and realized that the structure of the Army itself was Southern white sergeants that didn’t have any other way of getting a job and had no other way of being professional.

JAY: Clan meetings.

CONWAY: Yeah. And pretty much what–they were taking in, there was a huge influx of blacks then, but it was like they were preparing for Vietnam. They knew Vietnam was going to happen. And it was just sucking in black guys and kind of, like, programming them to get ready to be cannon fodder. And it started dawning on me then that, well, there’s a problem here in the Army. And I started working to kind of, like, with the other brothers, and we started–by ’65 we were organizing–it was just like they were organizing in Vietnam and so on–against the racism.

The clan was there in full-hooded body. They were holding meetings and whatnot. And so, eventually we decided to find out where they were holding their meetings, and we went and we beat the shit out of them, for the want of a better term, you know, because they were, like, putting little lynch–lynching symbols on the wall and stuff like that. You know. And so, in the day, because of their sergeant and their–the sergeants and their support system, they pretty much ran the Army bases. At night, we ran the Army bases.

JAY: In the next segment of the interview, we’re going to talk more with Eddie Conway about how he went from someone who, in his words, couldn’t care less to someone who became a fighter. In fact, that would become the defining thing about his life, I would say, the fight for the defense of his humanity.

Please join us for part two on Reality Asserts Itself with Eddie Conway.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

“Marshall “Eddie” Conway was an American black nationalist who was a leading member of the Baltimore chapter of the Black Panther Party who in 1971 was convicted of murder of a police officer a year earlier, in a trial with many irregularities.”

thank you Eddie for your courage and your beautiful spirit. I learned so much from you. Peace.

Thank you Paul, for theAnalysis and TRNN the window to the world through which we learned of the legendary Eddie Conway.