The Fed Attacks the Working Class – Robert Pollin

The Federal Reserve is trying to increase unemployment and strip U.S. workers of the small gains in bargaining power they have achieved in the aftermath of the COVID economic lockdown. Robert Pollin joins Paul Jay on theAnalysis.news.

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to theAnalysis.news. In a few seconds, we’ll be back with Bob Pollin to talk about inflation. Don’t forget, there’s a donate button if you come over to the website. If you’re on YouTube, hit subscribe. If you’re on all the podcast platforms, the best thing is to come on over to our website. One, it’s where you can make a donation, and two, you can get on the email list. I’ll be back in just a few seconds.

A recent article in the Economist points out that, quote:

“In August 2020, Jerome Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, described a shift in central bank’s policy framework. “The economy is always evolving,” he noted. “Our revised statement reflects our appreciation… that a robust job market can be sustained without causing an unwelcome increase in inflation.”

Two years later, the article quotes Powell as saying:

“Without price stability, the economy does not work for anyone.”

Well, we know what that means. That means raising interest rates to fight inflation. That’s me saying that, not the Economist. The article continues:

“Globalization served as a gigantic shock absorber from the 1980s into the 2010s, noted Isabel Schnabel of the European Central Bank, such that shifts in demand or supply were easily met through corresponding adjustments to production rather than wild swings and prices. Now that flexibility is at risk.”

The article continues to explain that with “the pandemic lower population growth, including in low wage areas of the world like China and other places, and aging, there will be less labor available.” So, quote, “workers may thus enjoy more bargaining power in the future, spurring wage growth, and make life harder for inflation-fighting central banks.” I guess we should get out our violins for the poor central bankers.

Now, joining us is Bob Pollin. Bob is co-founder of the PERI Institute, the Political Economy Research Institute in Amherst, Massachusetts. He’s an author of the book he co-authored with Noam Chomsky titled Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal: The Political Economy of Saving the Planet. Thanks for joining us again, Bob.

Robert Pollin

Really happy to be on. Thank you, Paul.

Paul Jay

So what do you make of that quote from the Economist? They kind of say what you’ve been saying. The issue is, how are we going to deal with inflation? Meaning, how are we going to suppress wages?

Robert Pollin

Well, that is exactly what they’re saying. Let’s suppress wages. I would say their diagnosis of the cause of the inflation being centered on wage increase and wage increase being the result of workers getting too much bargaining power is misplaced. On top of it, their broader analysis that the bargaining power of workers is resulting from slower population growth and the breakdown of globalization, I think, is not correct.

I think that there have been workers who have gotten more bargaining power as a result of coming out of the pandemic because we have these huge stimulus policies in the U.S. and the other advanced economies. That put a floor on the economy, and it led to an increase in employment. That’s good. That was good. I mean, the stimulus policies were really unequal. There are a lot of bad things about them, but they did manage to prevent a depression. If we had a depression, we wouldn’t be talking about inflation; we’d be talking about deflation. We’d be talking about increasing unemployment drastically, wages falling, and incomes falling. We would be talking about debt defaults and the financial markets in tatters. That did not happen. For all the bad things we can say about the stimulus policies, that didn’t happen.

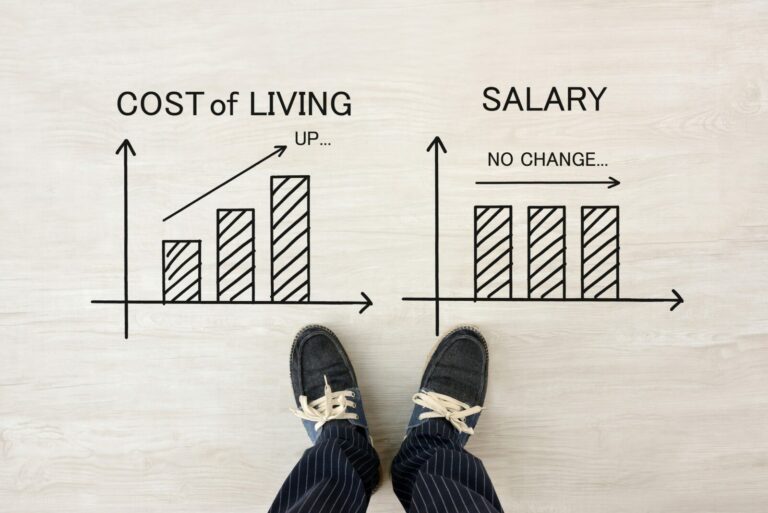

Workers did get some modicum of increased bargaining power such that in the U.S., the wage and dollar terms went up by about 5% over the last year. That’s the average. At the same time, inflation is 8.3%. So workers’ wages haven’t kept up with prices, even if we say that there has been some improvement in wage bargaining. So that’s the real context, the broader context in terms of workers getting more bargaining power; if we look at over the last 50 years broader context, workers’ wages are no higher than they were 50 years ago– at roughly $25 an hour in today’s dollars. Productivity has increased two and a half times. So if workers’ wages have gone up over the 50-year period with productivity and not a penny higher, workers would be making over $60 an hour. So that’s the context.

The notion of attacking workers having achieved a modest increase in bargaining power after this Covid lockdown really misplaces the problem. The fact that workers have gotten a slight increase in bargaining power is an extremely positive development relative to where we were under the Covid lockdown.

Paul Jay

Now, we talked about this last time, but it’s worth saying again. The big causes of inflation now, if I understand it correctly, number one, the spike in energy prices, and two, the global supply chain issues— anything from on the food side to the semiconductor chip side. There are a lot of factors that have absolutely nothing to do with wages. That’s correct?

Robert Pollin

Yeah. The big jump over the last year was energy prices. Gasoline and heating oil were 50-60% higher than a year ago. So that was due, number one, to getting the supply chain back up after the Covid lockdown. Then the oil companies take advantage of these shortages, gauging and marking up their prices because they have the price and power to do it. That is starting to get reduced. Right now, the gasoline prices have been flat. They are actually declining in the last two months.

We are seeing a similar pattern now in the food sector, but not to the same extreme. Number one, we have the supply chain breakdowns, and then we have because of the climate crisis, we have droughts, and because of the war in Ukraine, which has created food and wheat shortages. On top of that, we have the commodities futures market trading on food, trading on energy in the commodities market, looking at expecting future prices, and we’ve seen speculative spikes in prices there for the future prices, which then feed back into the current prices. So that combination has been pushing up food prices to a significant degree. That is all independent. It’s not getting into the workers’ pockets; it’s getting into the pockets of the food multinationals.

Paul Jay

Now that material I quoted from the Economist, Powell, just two years ago is saying essentially there’s been a structural change. I remember at the time when the pandemic hit, and there was all this talk about massive stimulus. I would listen to Bloomberg radio, and I would hear Wall Street character after Wall Street pundit talking about how we don’t need to worry about inflation; we need to pump money into the system. There’s been a structural change now. We can do all this without inflation. Powell seemed to agree with all of that. The pandemic effect, in theory, at least, the higher energy, even the war in Ukraine, they’re relatively, in the long scheme of things, temporary, one would think. Now they’re talking as if there’s a new structural change, that kind of ability of the system to have more stimulus without higher inflation. Now they’re saying, oh no, that’s not true anymore. I mean, what changed in their heads?

Robert Pollin

Okay, so as long as we’re quoting Powell, here’s a quote from just a year ago. When they introduced the Biden stimulus policies in March 2021, he said, “I’m much more worried about falling short of a complete recovery and losing people’s careers and lives that they built because they don’t get back to work in time.” So as of only a little more than a year ago, the Fed and the U.S. administration and globally, the issue was, it’s easy to forget now. With the pandemic, we had basically a global lockdown. U.S. unemployment went from February 2020 to April 2023 from 3.5% to 14.5% in two months. That’s what we were staring at. The stimulus policies were addressed to fight that. That was the correct move, in my view. As badly designed as stimulus policies were, they were better than not doing them. That’s what Powell is saying.

Now what? Now what we have is the impact of those policies. It’s true that people did not anticipate the extent of the supply shortage and these supply chain breakdowns, including me. I can’t say that I said, oh, of course, this is going to happen, and we’re going to get 8% inflation, but that’s okay. I don’t know that anybody recognized that because we hadn’t had serious inflation in 40 years.

Now that it has happened as a result of the supply chain, we’re starting to see these other facts. In the face of supply chain shortages, you have the businesses having corporations, big businesses, marking up prices, gouging, given this opportunity due to the supply shortages, and that’s something that is the primary driver. So if you look at the change in the profit share of business, that is the biggest single driver. It’s not workers’ share going up, workers’ share of income going up with the wage increase; it’s the profit share of increase, a profit share of total income, of the total pie going up faster than the wage share. If the profit share were not going up faster than the wage share, then we would have inflation at exactly 5%, which we don’t. So that’s really the driver.

In terms of the wage increases, yeah, but remember, wages went down during Covid. So we’re observing– thank goodness– we’re observing some catch-up. The biggest single area of wage increase since Covid has been in hotel restaurant workers, who faced huge layoffs and wage cuts during Covid. Now we’re getting some catch-up. You know what, basically if we’re saying we can’t absorb those kinds of wage increases, the real message is U.S. capitalism, global capitalism, U.S. capitalism cannot function with workers getting a bigger share of the overall income pie.

We’ve had 40 years of huge inequality, and the basic message is that’s the way capitalism has to work. Inequality is a permanent and increasingly entrenched feature. If we want to think about reversing inequality, then yeah, wages have to go up relative to profits. A little bit of that is what we experienced in some sectors.

Paul Jay

I know one of the arguments that are given is inflation; the classic definition is too many dollars chasing too few goods, and if the government in the stimulus gave people money to spend and because of the pandemic there are less goods, that’s inflationary. Even if that was true for a bit, one would think that effects are long gone.

Robert Pollin

Well, in a very simple framework, yeah, there is truth to that. Again, let’s put it in reverse. Would we have rather had too few goods, too little spending? Would we have rather had a deflation and depression? We could have had that. Prices could have collapsed. Remember, if prices collapse, that means people can’t pay back their debts because their debts are fixed in dollars, but now they have less income. We would have seen a financial collapse. That’s what free market capitalism would have delivered for us over the last two years.

Instead, we have this inflationary issue which in part reflects workers catching up a little bit. Still, much more than that, it reflects the supply shortages due to the lockdowns that occurred during Covid and businesses taking advantage. Initially, it was the fossil fuel companies, and now, it’s in the food sector.

Paul Jay

One thing I thought was interesting about that article I quoted in the Economist is that maybe they’re looking in a longer-term structural way and that the pandemic sent them an alarm that you can’t trust globalization anymore. I think they, being big capital, were surprised themselves how easily the supply chain fell apart on them. Two, with the rivalry with China, and certainly still China being the main source of skilled discipline, relatively cheap labor, although getting less cheap by the day, which is part of the problem for them. They can’t rely on– as on that quote at the end of the article– they can’t rely on cheap offshore labor to force down American wages. They’re going to have to find other ways to keep American workers’ wages low.

Robert Pollin

Yeah. So if we go back to, say, the 1990s, then Fed chair Alan Greenspan was quite candid. He said even with low unemployment; we do not see upward wage pressure. The reason he said that workers are, in his words, traumatized. We have a traumatized workforce, meaning that workers are afraid of losing their jobs and bargaining power due to globalization and the attacks on unions. He didn’t say that was negative, by the way. He said that’s just the reality. That has been the reality since the early 1980s with the onset of neoliberalism. That is the core feature of neoliberalism that has kept wage inflation down, even at low unemployment. It meant that in all the models that we economists have of the relationship, low unemployment means higher inflation. The so-called Philips Curve. It broke down because even at low unemployment, workers weren’t getting wage increases.

Now, what has happened now, okay, there have been these supply breakdowns in the global supply chain. To some modest extent, yes, you have wage increases in China. It means that workers have started to get very modest wage increases which aren’t even maintained at an equal rate with the price increases. Even with workers getting the modest wage increases that they’ve gotten over the past year, on average, businesses have been able to mark up more than the wage increases. That’s why the profit share has gone up.

It isn’t a given that every time a worker gets a raise that the businesses have to mark up their prices the equivalent amount. We could see the profit share go down. That hasn’t happened. We could also see productivity go up and workers just getting a share of the overall productivity gain, which also hasn’t been true for 40 years. Productivity goes up. In other words, the average worker produces in the day goes up. Does the worker get more money as a result? No, that’s not what we’ve been experiencing. So if we’re starting to move even slightly off of this neoliberal model, that’s a positive. Therefore we want to shift the income distribution to be more equal.

Paul Jay

Which would include taking serious steps to reduce the amount of monopolization in the economy.

Robert Pollin

Yeah.

Paul Jay

I mean, it used to be there would be so much competition. It wasn’t so easy just to raise prices because workers in a specific sector won more wages. You’d still have to worry about the other sectors that maybe hadn’t quite yet won those wages, and competition led to a certain amount of obstacles to simply passing on.

Robert Pollin

Right.

Paul Jay

We are so monopolized now it’s so much easier for them to just pass on.

Robert Pollin

Yeah. To its credit, the Biden administration has raised this point with respect to inflation control. Let’s start looking into enforcing the antitrust and anti-monopoly laws that are in place that have languished again for 40-odd years. Some economists, including Larry Summers, the well-known Harvard macroeconomist, are arguing about it. That stuff has nothing to do with inflation. Anyone who thinks that can impact inflation is an economic illiterate. Well, obviously, that’s not true. Again, if you just look at the relationship between wages going up and business price markups, at least we can drive down the degree of price markups through anti-monopoly measures that are already on the books. They haven’t been enforced to any significant degree, but at least it is in the discussion to the extent that it hasn’t been.

Paul Jay

I was watching Fox news this morning, which I don’t do very often, but I did today. They had this graph which showed how inflation has risen; the CPI has risen. It all starts from the election of Joe Biden in their graph. I’m not any great defender of the Biden administration; it’s kind of funny because the big spike takes place the day he gets elected, which is kind of hard for his [crosstalk 00:21:36]. There’s a big spike before the big stimulus package hits. Of course, in the Fox rhetoric, it’s all about the stimulus package causing the spike.

Robert Pollin

Well, look, the first stimulus package was in March 2020. Trump was president. The stimulus package in March 2020 was the same size as the one in March 2021. Then on top of that, there was another one in December 2020, and Trump was still president. He lost the election. He didn’t concede it, but by then, he had lost the election. Nevertheless, he signed another stimulus package. The Federal Reserve, on top of these government spending programs, the Federal Reserves purchases of assets on Wall Street began in March 2020– $4 trillion over the course of a year. That was all before, or mostly before, Biden had come into office, much less Biden doing, hit the third stimulus program.

The stimulus programs did contribute to preventing a collapse. If you want to call that inflationary, then I say yay to inflationary measures because the alternative would have been worse. Again, imagine; unemployment went from 3.5% to 14.5% in two months. Unprecedented. Didn’t even happen in the 1930s. Over the 18 months from March 2020 to September 2021, one-half of the workforce filed for unemployment insurance. Half of all people in the workforce had experienced unemployment. These stimulus measures were trying to counteract that, and they succeeded.

Again, they were unfair. They could have been designed much better, but they prevented massive debt deflation and depression. The result is we did get these supply shortages which are now feeding into the inflationary pressures because of the power of the big corporations to mark up prices above wages.

Paul Jay

So we’ve seen in the context of all of this a rising militancy amongst workers. As we record right now, there was recently just a vote amongst railroad workers who rejected a deal that their union had made, and there may be a strike coming. It’s a reflection of what’s happening right across the country. There’s more organizing going on. You can start to see what it means if you’re thinking like a big capitalist, what it means when workers start to have a little leverage. As you say, it’s only a little leverage, and look what’s going on. It’s not a surprise that’s what’s preoccupying big capital because they don’t want more of this.

Robert Pollin

No. Pre-neoliberalism, from 1960 to ’73, the average real wage of the average worker did go up by 50%. So workers did have bargaining power way back when. They were able to generate improved living standards and a more equal income distribution. That was the outcome. From 1973 to the present, we’ve had stagnant wages, and we’ve seen the ratio of the average workers’ wage to the average CEO raise. The CEO’s compensation has gone up tenfold relative to the average worker. To put it in very round numbers, the average worker was making a little bit over $50,000 in 1973. In today’s dollars, they are still making a bit over 50,000. The average CEO made one and a half million around 1970. The average CEO now makes 15 million. In the world of today, where the average CEO is making 350 times more than the average worker, that’s the world they want to defend. They don’t want workers to have any bargaining power.

Yes, it’s exciting to see the fight back that has resulted, yes, in part due to the relatively somewhat tighter labor conditions that have given workers some leverage. Not a lot, but some.

Paul Jay

So the message is if you’re a worker watching this, get organized. If you are organized, get organized even more to fight. You better stop believing this system is going to deliver anything more than this to you.

Robert Pollin

On its own, right. That’s been the message for 40-50 years that we have an economy in which all the benefits accrue to the rich, and that’s why inequality has risen so much. Unprecedented. Unprecedented even relative to before the Great Depression and even after the financial crash in 2008-2009. We did see some dip in what the Wall Street and CEOs were making, but it went right back up due to the fact that we had stimulus policies then. Now we have another round. The stimulus policies this time, yeah, we’re starting to see workers organize to get some of those benefits. That’s a positive. That’s why the idea of using an anti-monopoly policy to limit price gouging is a very positive development, and it’s a way to address these issues about inflation today.

Paul Jay

When I grew up, auto workers, and I used to know some; it was pretty common in our neighborhood for workers to have a car and maybe a second car, a cottage. They were never concerned about their kids going to university. They could afford it. The people working in the auto industry or transport, certain sectors of the economy, were doing pretty damn well. Then in ’07-’08, they came after the auto workers. They restructured so that a starting auto worker, I believe, was making $14 an hour.

Frank Hammer, for many years, worked there. He may not have been the only one that said this, but he said this is the first time that someone working in the auto industry can’t afford a car. They went after the top tier of the working class too, and now they’re in the same boat.

Although there used to be this mentality amongst the auto workers: we have a good health plan; who cares about Medicare for all? Workers are all in the same boat now. The need to give up some of the political illusions that come from that tier of the working class who actually are the ones that still have a lot of leverage, people working in those sectors of the economy, if they go on strike, they close down the economy like what we might be seeing in the railroad.

Robert Pollin

Yeah. Well, the idea of workers gaining leverage is really at the heart of all of this. I read all the technical economics papers, and it’s so interesting that we go through all these fancy calculations and models, but fundamentally they’re all about, gee, how much bargaining power are workers actually getting and what are the ways through which we can limit it and at what point our work is going to start losing bargaining power. That’s at the core of these economic debates going on right now.

Paul Jay

Alright, thanks very much, Bob.

Robert Pollin

Okay, thank you.

Paul Jay

Thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news. Don’t forget, there’s a donate button. We can’t do this without it and subscribe. Most importantly, we need to strengthen our email list. Thanks again.

Robert Pollin is an American economist and self-described socialist. He is a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and founding co-director of its Political Economy Research Institute. He has been described as a leftist economist and a supporter of egalitarianism.

I don’t like to listen or watch. Please post transcripts.

Transcript is there. Please click the transcript tab