Vietnam Body Counts and America as Victim – Christian Appy on RAI (4/5)

This interview was originally published June 2, 2015. On Reality Asserts Itself, Mr. Appy says the Vietnam War killed millions of Vietnamese and tens of thousands of American workers – yet the mythology is America as a whole emerged as the victim.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay. We’re continuing our series of discussions with Christian Appy about the Vietnam War and American identity. Thanks for joining us. And I’ll just remind everybody again, that’s more or less the name of your book, American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity. And you teach at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. So let’s just pick up where we were. We were about to talk about how the narrative is not only do we have to be the toughest in the world, but we’re also a victim, which is why we then have to go be so tough. But everything gets turned into victimhood. But before we get completely into that, a little bit of a segue–but it’s connected to it. If you talk about Vietnam, we’ve talked about the real victims, who were primarily the Vietnamese people. But also, if you go to America, the real victims were African-Americans who paid with their lives in completely unequal numbers.

CHRISTIAN G. APPY, AUTHOR, AMERICAN RECKONING: Certainly at the beginning of the war. In ’65 and ’66, more than 20 percent of American fatalities were African-American, which was almost twice their proportion of the population, though over the course of the entire war, that percentage falls to about 12.5 percent, which was still a little bit disproportionate. But I really think the military, in response to civil rights activism and calling out the early disparities, began to try to reduce the number of African-American casualties. But it is clear they were certainly more vulnerable to the draft. My own view is that the disproportions are primarily class-based. This really was a working-class war, and it was under a draft system that was biased in almost every possible way.

JAY: For example?

APPY: Well, for example, the most obvious is there were student deferments for people who were enrolled as full-time college students, who could at least put off the draft for four years and then were often able to find other ways out. And even exemptions that you might have expected to advantage poorer kids didn’t work out that way, for example physical exemptions. You know, you would think that poorer kids would not have as much access to medical care or nutrition, so that they would get more medical exemptions. But in practice, when you went for that military medical exam, if you had a note from a private doctor testifying to a long history of chronic asthma or–

JAY: Backache.

APPY: –or skin rashes or a bad knee from a football injury, anything, you were likely to get that exemption. In some draft centers they actually would set shout out, all you guys with letters from your doctors, over here. And the rest of them, of course, were, especially when the draft quotas were exploding, regardless of high blood pressure or other conditions, were just rubberstamped. So, yeah, drafts could be completely random, but this one wasn’t. It was really put in place, going all the way back to the late 1940s, our first peace-time draft, as an exercise in social engineering in which they explicitly said, we want to channel the entire generation to serve the national interest. We don’t need everybody to be in uniform, but in a nuclear age we need a lot of physicists, we need a lot of teachers. We even need English majors to write better propaganda. So let’s encourage people to go to college and graduate student by keeping them out of the military; meanwhile, we’ll draw working-class kids into the military to do that necessary part of the job.

JAY: I once interviewed a Canadian general who–I don’t why he was so blunt with me, but made it really clear that you really do need soldiers who are not educated; otherwise, why are they going to go out and die for you?

APPY: Yeah. That’s true. And then one of the things that’s so interesting about Vietnam is the degree to which over time soldiers themselves, including 18- and 19-year-old draftees, become increasingly disaffected with the war, because once they got to Vietnam and they saw the stark contrast between what they had been told and what they were experiencing, they immediately realized, we’re not saving anybody here, we’re not being received as liberators; all we’re doing is being sent out into the country to kill people. And their commanders are not too fussy about who we kill, as long as that body count is being built up. And that, of course, was the chief measurement of success in Vietnam.

JAY: Yeah, people who didn’t live through that era don’t remember the news reports and the extent to which body counts were like football goals.

APPY: Yeah. Every night on the news they would tally it up, and it would always be something like, “This week in Vietnam, 2,200 Vietcong and North Vietnamese were killed and 250 Americans.” And, you know, those numbers would always look like, well, we must be winning, ’cause–.

JAY: The other story which I think–which kind of cuts against this whole American exceptionalist narrative and there as liberators and then later as victims, but the extent to which, as you were saying, soldiers started to resist while they’re in Vietnam, especially African Americans. I know I was in Toronto at the time, and American deserters and draft dodgers would come to Toronto in great numbers, and I heard many stories about African Americans, even to the extent of having even study groups that were working with the Viet Cong, and deals made where if you wore a red bandanna, you know that if a sniper was coming, you would miss the sniper and they would miss you, particularly amongst African Americans, although I don’t think only.

APPY: Yeah, that’s a whole wonderful sort of secret history of the war that needs to be written, because it’s clear that over time African Americans were joining together and educating themselves and bringing from the States the new politics of black power. And Radio Hanoi was broadcasting through Hanoi Hannah, explicitly addressing African-American troops and saying, you know, soul brothers, this is not your war; your war is at home; you know, you should be joining us. So, yeah, that is a whole really interesting part of the history.

JAY: This is where the term fragging came to be known.

APPY: Yes. This is when American troops actually began to violently turn against their own commanding officers. And they used the term fragging because that comes from the word fragmentation grenade, which was the weapon of choice because, as they would say, it leaves no fingerprints. You could roll it under an officer’s bunk or hook it up into a privy. And typically the targets were officers who were the most gung ho, careerist, let’s get out there and fight aggressively at a time, by the late–by ’69 and ’70, many troops wanted to avoid combat and did. They would go out. They would be ordered, say, to go out on a night ambush, and they would go out, but they would find a place they thought was relatively safe, and then they would get on the field phone and call in a fake coordinate to say that, oh, yeah, we’re where we’re supposed to be, but they weren’t, or they would outright refuse, sometimes, to follow their officers.

JAY: Part of the narrative that starts to develop as victimist is American soldiers as victims, but not the soldiers we’re talking about, not working-class soldiers losing their lives. The soldiers that are victims are people that, in the need for war–for example, the My Lai massacre–slaughter people, but they’re the victims, not the people they slaughtered, ’cause they got charged. Tell us a bit about the My Lai story and how–’cause I think this is a very important point of where this soldier America’s victim starts to develop.

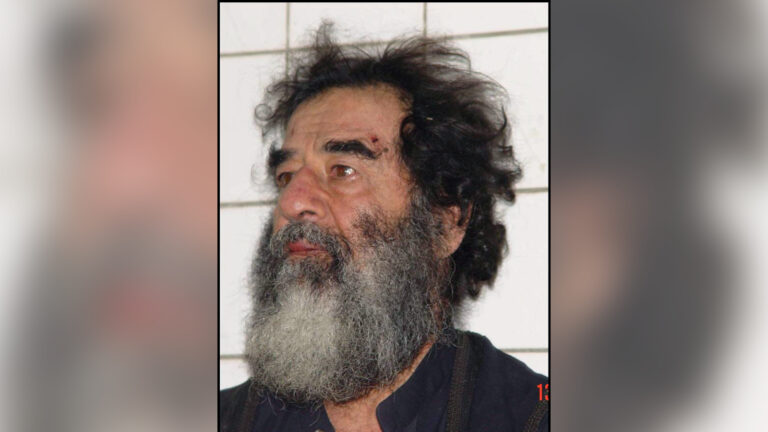

APPY: Well, in March 1968, a company of American infantrymen went into a village, South Vietnamese village of My Lai. They had been told in advance that this would be an opportunity to really get back at the enemy, because there was going to be a big force of Viet Cong in that village, and that they were going to go in there and kill everything that moves. But they quickly realized, just walking into the village, that there was no enemy there. They received not a single round of hostile fire, but began to shoot up the village, and killing civilians, one or two at a time, ten at a time, sometimes rounding up as many as 100 at a time. And this was not some kind of rapid, spontaneous spasm of violence; this was systematic slaughter. Over a period of four hours, even with breaks for cigarettes and meals, this company of troops murdered, at close range, some 500 mostly women, children, and older men.

JAY: ‘Cause the men from the village had left to fight somewhere.

APPY: The younger men, the military-age men, you know, were either off fighting for the Viet Cong or for the South Vietnamese military and were nowhere in sight. And it’s true that many Americans were horrified by it, and it did begin to awaken a full-blown moral critique of the American war, but a shocking number of Americans also said things like, oh, this couldn’t have happened, this must be communist propaganda, or these photographs have been faked. Or more typically they would say, well, you know, this kind of thing happens in all war; all armies produce atrocities like this. But what’s interesting to me about that claim is even if you believe it, you really are throwing out the door this idea of American exceptionalism, ’cause we’d always said we have a higher price on life than others. So if we’re excusing ourselves just because other people commit atrocities, we’ve lost our unique virtue. But you’re right, there was some sympathy with those veterans at My Lai, and particularly Calley, who was the only person charged and convicted with war crimes that day. And people rallied around him and saw him as a–.

JAY: Including Jimmy Carter.

APPY: Including Jimmy Carter. And he was quickly put under house arrest rather than the stockade, and effectively paroled by Nixon after only three and a half years of this cushy house arrest.

JAY: It seems to me that the post-Vietnam narrative–and you talk about this in the book–to make America as the victim, a big part of this is that we only lost ’cause we were too humane to use nuclear weapons, and if we’d only used nuclear weapons, which we had the power to do, we never would have lost. And that connects to the Calley narrative, that our soldiers, who did what needed to be done, they became victims, because we use them as scapegoats, and this whole narrative that we weren’t really weak.

APPY: Right.

JAY: But it does beg the question, I guess, which is: why didn’t they use nuclear weapons? Because that’s the big argument: we only lost because we didn’t. Well, why didn’t they?

APPY: Yeah. Well, it’s true that there was always about a quarter of Americans who said that if that’s what victory required, we should use nuclear weapons. But I think the real break on that for Johnson, and even for Nixon, was the possibility that with nuclear weapons in the hands of both the Soviet Union and China, that to use them in Vietnam might really pull the trigger on a nuclear war, in which we, too, would become the victims. I think if we had continued to have a monopoly on nuclear power, who knows? We might well have used them. But that really was–that was a break that prevented it, the main break.

JAY: And also it would have enraged Americans public opinion.

APPY: Yeah, that too. I mean, they understood well enough that there was already such deep underlying hostility toward the aggressive tactics that we were using and the massive loss of civilian life that one could only imagine the uproar domestically if that had happened.

JAY: It could have given rise to a complete break with the whole American exceptionalism narrative.

APPY: Yeah. True. Absolutely.

JAY: I mean, you do that, what’s left of that narrative?

APPY: Right, because–.

JAY: The reason I’m pushing this is that the right that tries to–sections of the right, at any rate, that try to make America–

APPY: Refight the war,–

JAY: –refight the–.

APPY: –it was a noble cause, it should have been fought and could have been won.

JAY: Yeah, that it was totally in the self-interest of the American elite not to use nuclear weapons. It’s not there was some great moral higher calling here.

APPY: Right. Right.

JAY: Maybe amongst some, but not the predominant–.

APPY: Yeah. But the growth of this victim culture, as I call it, or–“Victim Nation” is the title of one of my chapters–really is a product of this defeat in Vietnam. I mean, prior to that, we had really lived under a kind of victory culture, where victory was just simply assumed. But once that defeat happens, there is a growing sense that we’re not only the victims of that war, but in a sense that we have been faced around the world by these inexplicable forces of anti-Americans committing these kind of hate crimes for reasons that we could never quite understand. And there was, of course, a right-wing version of it, that we were victims of liberals and the media and radical students who were preventing our boys from fighting as fully as they should have, or with one hand tied behind their back, as Bush senior once said. But there was also a kind of liberal version of that, which is that what we really need to do in the aftermath of that very controversial, divisive war is to heal our nation, and even a lot of broad support for Reagan’s idea that we have to recover that pre-Vietnam pride and patriotism, and of course power, and overcome this so-called Vietnam syndrome, which he saw as a kind of malady which was inhibiting us, making us way too gun shy, that we had to overcome this reluctance to use military might. And one of the things that I think was effective politically is to suggest that one of the most shameful things about the Vietnam War, maybe the most shameful thing, is the way we treated returning American Vietnam veterans, that shabby treatment, and that the first act of citizenship should be to thank those veterans for their service. And that’s really been part of our political culture ever since: whatever you may think of the wars that are being fought in your name, you must honor the service and sacrifice of soldiers. JAY: And let’s talk about that just part of this recouping the American vision of strength and tied with the American soldier as victim now is towards the end of Vietnam. There’s all the antiwar protesters are, you know, talking about the massacres, even the media by this point after My Lai is talking about some of the massacres, and everyone’s getting fed up with the war. Now it becomes the soldier, we have to support the soldier. And one of the songs that was so important from that period is the Green Beret. We’ll play a little bit of it now. …

JAY: So that song was 1966. I mean, it’s incredibly popular. It was high on the charts, right?

APPY: It was the number one pop song of 1966, which is remarkable, because by that time you had the Beatles, the Stones, even a number of antiwar songs–“Eve Of Destruction” was a popular hit the year before.

JAY: It shows the division in America.

APPY: It shows the division in the mid ’60s and how it was possible to kind of like both songs. I think as a kid I did, in part because “The Ballad of the Green Beret”, it makes no reference to bloody slaughter, or even Vietnam, and is a song about elite service to the country in support of freedom and those oppressed. I mean, that’s sort of the Green Beret motto, freeing the oppressed. So it’s a strange period in the mid ’60s. Just a few years later, of course, that song would be easily ridiculed by anyone who was opposed to the war as just broad-brush propaganda.

JAY: But it does begin kind of this narrative of support the troops and forget about the foreign-policy, as if the–.

APPY: Yeah, yeah, though–I think that you’re right, I think, to identify the origins of it earlier, that early, but it doesn’t really take off until the Reagan years. And you might even point to the construction of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1982. And students I had in the years after that would often come to class, and I’d say, well, what images of the Vietnam War are in your head right now? And they would always say the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. And it was almost as if what they had learned was the one thing you do when you talk about Vietnam is to pay homage to the dead, American dead, the American dead and American veterans. And even as one student memorably told me, I always felt like the Vietnam War was a kind of dark family secret that you weren’t supposed to talk about around the children. I had questions, but I was afraid it might offend someone, particularly veterans. So it was a way of dampening–that sort of routine thank you for your service idea really did effectively dampen open debate and dissent.

JAY: I just want to go back a step. I read a quote earlier from your book. It think it was an assistant secretary of defense that said, by the end of the war, the reason we’re still in the war is 100 percent to prove to the world that we can’t lose a war; there’s no other objective that matters. Well, America lost the war, which means it lost 100 percent in Vietnam. So the need to recover the ability to be able to threaten people, to be able to tell the world, yes, Americans are willing to lose lives, you’ve got to rebuild the whole narrative. And so I guess this is part of your argument about the victim, that we’re victims; we have to be prepared to fight again. And the Iranian revolution is really the beginning of a whole new phase of this.

APPY: Yeah, absolutely, which culminated, of course, in the hostagetaking of 52 Americans, who were held for 444 days. And that–talk about a media sensation. That was wall-to-wall daily coverage, in which we were told, you know, America held hostage, day 78. It wasn’t just 52 professional foreign service officers and a few CIA agents and a few Marine guards; it was the whole nation somehow being held under the thumb of this these crazy Iranians who are saying death to America and burning the American flag. So one of the remarkable things that comes out of that is when the settlement is finally negotiated and the hostages are returned, they receive this hero’s welcome, tickertape parades, White House party, season tickets to professional baseball games, yellow ribbons everywhere. And that ushered in, I think, a period in which we redefined heroism as not putting your life on the line for some great and just cause, but simply putting on a uniform and in some form or fashion serving the country.

JAY: And I think to a large extent a lot of the liberal and even left of the country kind of buys into this. Like, you know, thank you for your service and so on and so on. I mean, I understand not blaming ordinary soldiers for U.S. foreign policy, but the critique of U.S. foreign policy winds up getting so mitigated sometimes when it’s all support the troops.

APPY: It does, because the line that often follows thank you for your service–you often hear it all the time–is the, you know, thank you for fighting for our freedoms, even if the evidence doesn’t suggest that that’s what they’re actually being sent to fight for. But I also think it’s really a completely empty gesture. I mean, I’m all for trying to communicate with the military and with veterans, and I talk to ROTC students–I like to talk to them–at University of Massachusetts, ’cause I think we have this huge gulf between the military world and civilian society. We now rely on this tiny cohort of people to serve in the military. So I think a better question would be, you know, would you please tell me about your service? And I think that’s to treat people with full humanity, because soldiers and veterans are complicated people, and they represent the widest possible spectrum of political views, and we could learn something from them about the wars we’re fighting.

JAY: And just to finish off this American of narrative, of course 9/11 becomes our contemporary we’re the victims. And I remember in the days just following 9/11, I was executive producer of a debate show on CBC in Canada, and the morning we were going to do the show about what just happened, just days after the attacks, we started it by saying, if President Bush had asked us to grieve, we wouldn’t be doing a show tonight, but he asked us to go to war, and we have a right to debate whether we are or not. That morning, newspapers throughout the English-speaking world had had almost the same editorials and op-eds, which is, if you try to tie 9/11 to U.S. foreign policy, if you talk about blowback, you’re blaming the victims and you’re serving the perpetrators, you’re serving–you’re allying yourself with terrorists. So you weren’t even allowed to have a conversation why the United States gets targeted. And in one of bin Laden’s letters to Americans, he made a pretty good comment. I don’t know who really wrote it, if it’s him or somebody else. But he said, if we really were targeting democracy, than why didn’t we attack Sweden? You know, it’s not for no reason all this stuff happens, but it’s the flip side of the coin: you have to be strong, but the victimhood justifies the strength.

APPY: Right. No, we never asked that forensic question, why did they do it, what were their motives. It was just this idea that they must hate us for–and then Bush would say, for our freedoms or out of jealousy or something, some crazy explanation. And it was a great missed opportunity. I mean, in every crisis there is often an opportunity. And the moment there was to reach out to the entire world and say, now more than ever we really understand what other countries have suffered and we have thankfully been free of–you know, attacks on our own soil–and we need to learn from you and work with you to try to move forward in ways that might prevent this from happening. Instead, of course, Bush just drew a line in the sand and says, you’re either with us or against us, giving no flexibility for people to say, well, we don’t want more terrorist attacks, but we have a different way of approaching it than declaring global war.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of our interview with Christian, we’re going to talk about how many of these themes continue to play out today. Please join us on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

“Christian Gerard Appy is a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He is widely known as a leading expert on the Vietnam War experience. The most recent of his three books on the subject is American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity.”