The Rise of the Big Banks – Costas Lapavitsas on Reality Asserts Itself (pt 3/8)

This interview was originally published on May 24, 2014. Mr. Lapavitsas says that large-scale industrialization created the need for massive amounts of capital and big banks, a process that developed an aggressive global capitalism.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And this is Reality Asserts Itself with our guest Costas Lapavitsas, who now joins us in the studio.

Thanks for joining us again.

COSTAS LAPAVITSAS, ECONOMICS PROFESSOR, UNIV. OF LONDON: Pleasure.

JAY: So, just quickly one more time, Costas is a professor of economics at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. And his most recent book that just hit the shelves is Profiting without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All.

So let’s talk about the history of finance, ’cause of lot of people see this issue as, you know, you get some lobbying by the banks and the government changes its policy. Like, in the Clinton years, you get rid of Glass-Steagall, which was a piece of legislation from 1930s that created a kind of wall between banks speculating and banks taking normal deposits. You weren’t supposed to have these things under one roof. But because they got rid of Glass-Steagall, all of a sudden we have 2008 and finance going wild.

But that’s not your view. Finance doesn’t come about just because of some particular government’s policy. So give us some historical roots of all this.

LAPAVITSAS: I mean, quite clearly this isn’t the case, although policy is very, very important in the context of finance. But to understand why we are where we are, you’ve got to start from below, as it were, from structural things.

Now, what can we say generally about finance and its history? I mean, a number of things are important to state at the outset, although we can’t go into them. But they are very important to understanding finance.

Finance, first of all, is a very, very old, very ancient form of profit-making, capitalistic profit-making, because you put some money into the realm of finance, you either lend it or you use it in a financial way, and you expect to make more money. And that’s the most basic principle of capital. You give some money–.

JAY: And if anybody’s been watching any of the–like, the HBO series, Rome, some of these most powerful senators are loaning money to the state to help pay for wars, and they charge interest.

LAPAVITSAS: Indeed. Indeed. You give some money, you receive more money back. That’s the basic movement of capital. And you find it in the Greek world. You find it in the Roman world. I mean the ancient Greek world. You find it in the Roman world. You find it in many, many other places long before societies become capitalist, what we recognize as capitalist. So this is a–finance is a very old form of profit-making, capitalistic profit making–very exploitative, very rapacious and aggressive and all the rest of it. So that’s the first thing to say about finance.

But, of course, we live in a capitalist society now, which is a very different thing, meaning that the whole of society’s organized on capitalistic principles, not just finance. So what can we say about finance in that context?

Well, I’m going to say three things which are important. The first is that when we look at the 19th century, which is when proper industrial capitalism emerged, productive capitalism emerged–.

JAY: Large-scale industry.

LAPAVITSAS: Actually, just before large-scale industry. When we look at that system of industrial capitalism, although not very big business, but nonetheless clearly capitalistic, finance is very much there. It’s impossible to have that without finance. But this kind of finance is a type of finance that supports production.

JAY: Yeah. So you want to start a business. You go to a bank. You get a loan. You go buy your machinery.

LAPAVITSAS: And that’s one thing you do. And then, as well, say you produce clothing or you produce various other bits of, you know, cloth, yarn, or whatever it is you produce. Then you use finance to give you liquidity, to give you credit to allow you to sell, to buy, and so on.

JAY: You’ve got to buy the raw materials, make your product.

LAPAVITSAS: That’s it.

JAY: And, in fact, you couldn’t do it without these kinds of [crosstalk]

LAPAVITSAS: There is no way.

JAY: It was needed.

LAPAVITSAS: That’s it. So it isn’t just obtaining finance to buy your machinery and to start the plant, but also for working capital, right, to get the thing going. It’s impossible to have industrial capitalism without that. So finance is very much there. It’s a complex system, but much smaller than what we’ve got now. And it supported production, basically. And that’s the kind of finance that Karl Marx knows, and that’s the kind of finance he writes about very well. And that’s the kind of finance that other great political economists know and write about, Adam Smith and so on before Marx, and some at the time of Marx, and so on. So that’s one kind of finance.

Then, towards the end of the 19th century, beginning of the 20th century, capitalism changes, and it changes in a very, very powerful way. We have the rise of what we might call monopoly capitalism in sort of Marxist terms. What happens there is that the unit of production, the unit of industrial and commercial production, gets much, much bigger. Big business emerges, basically.

JAY: Yeah, I mean, plants with thousands of workers.

LAPAVITSAS: Yes, and large corporations emerge. The United States is one of the classic countries in which this happens. American capitalism is transformed in the 1890s, 1900s, when all the various big businesses–we know the robber barons and everybody else.

JAY: And production becomes very social–this massive plant makes four parts of what will become an automobile.

LAPAVITSAS: That’s it.

JAY: And this is kind of a division of labor, and on a massive scale, which requires an enormous amount of equipment.

LAPAVITSAS: An enormous amount of equipment, therefore an enormous amount of capital. This becomes, in a sense, socialized production, but by capital, run privately for private profit. But it is a qualitatively different thing to what you’d have in the 1850s or 1840s, when you would be a small producer, maybe producing to export and so on, but nonetheless small and so on.

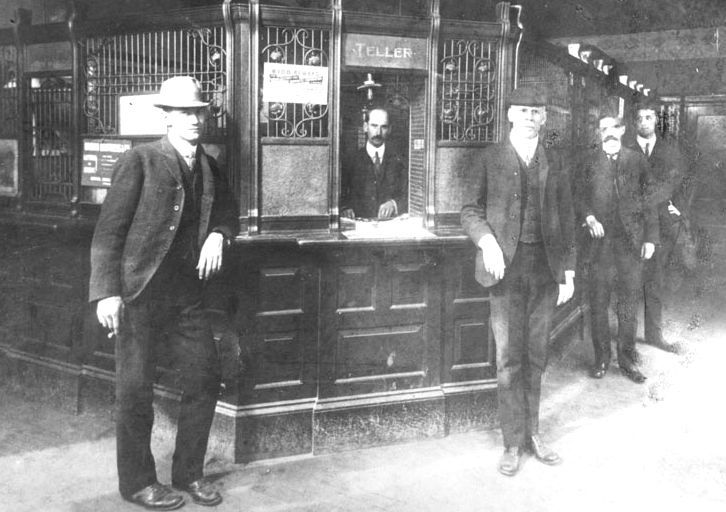

Finance also changes as big business emerges: big finance also emerges, big banks. So as big business emerges, I mean big industrial and commercial business emerges, finance also changes: big finance also emerges, big banks emerge.

The banks are themselves organized on corporate joint stock bases. These are giants. And they begin to do different kind of financial activity. It isn’t simply now providing working capital and some investment capital for the smaller producers. This is big stuff. This is banks operating the stock markets, facilitating the stock market transactions of these big industrials and commercials, playing international games–in a sense, high finance.

JAY: I mean, sometimes you have situations as you get into the 1920s–you know, a big bank is financing this company to produce something, is loaning money to this other, to that company, then loans money to this company, which has to buy stuff from that company. I mean, the banks are in the middle of everything.

LAPAVITSAS: The banks are in the middle of everything. They have a finger in every pie. They help capital to form these large concentrations, big business to emerge. They have a close connection with big business. And they often have a controlling influence over these big businesses.

JAY: And pumping the stock market,–

LAPAVITSAS: And of course they play the stock market.

JAY: –’cause they have an investment in such-and-such company, so they want a stock to go up, and they can start telling all these other people, oh, buy this stock.

LAPAVITSAS: That’s it. So banks can play these games. And profit begins to emerge through stock market operations in a systematic and very powerful way. And that becomes a source of all kinds of speculative and other kinds of profit-making activities.

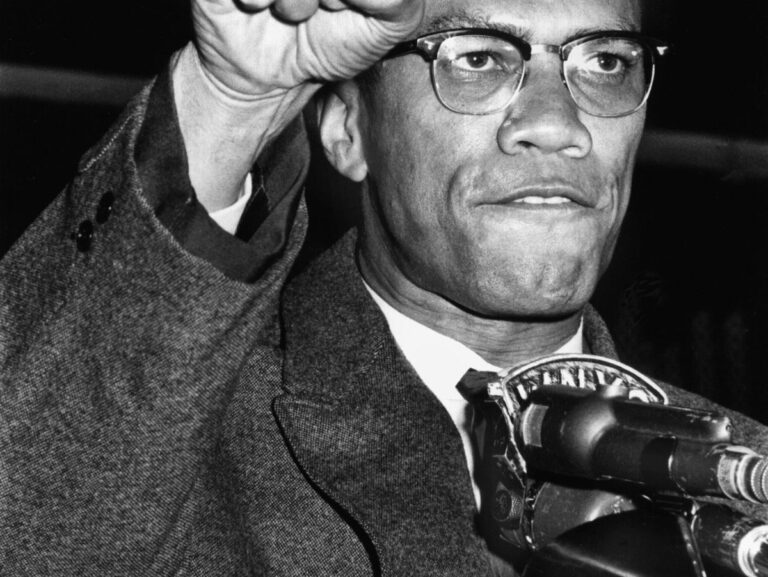

This kind of capitalism is clearly different from the capitalism that Karl Marx wrote about. It’s the capitalism that other Marxists began to write about, Hilferding, Lenin, and so on. It’s the kind of capitalism that supports imperialism across the globe. It’s a very aggressive capitalism. It’s a capitalism that wants to divide the globe, that militarizes, takes over the state, and fights against other capitalisms of this type. And you get all these global empires emerging. And then eventually you get world wars out of these capitals which have come to dominate their states. Okay? So in a sense, to me, that’s the first bout of the historic rise of finance. Finance emerges as a very powerful thing in capitalism now. It doesn’t just support production.

JAY: So there’s a graph which we’ll show on the screen here which shows the percentage of GDP, American GDP, and the percentage which is finance. And you can see in the graph that it goes–from the time of industrialization it goes up, up, up, and then just before the crash of ’29-30 it’s at this enormous peak. In the Depression it comes down some, and then in World War II it comes down significantly. I mean, talk just a little bit what that is, and then we’ll move to the second phase.

LAPAVITSAS: That’s a very, very important thing. Now, we have then this first rise of finance. And it’s associated with the First World War and everything that comes after that, the speculative orgy of the 1920s that finishes was the Great Crash in the United States and elsewhere.

Then the world in the 1930s goes into deep, deep trouble. Global economy doesn’t work. The world market splits into very many different parts that don’t really particularly trade with each other. And then politics also becomes deeply problematic. Fascism emerges in many parts of Europe. There is the Soviet Union, with communist regime in a large part of Eurasia too. The world looks like a very unstable, very different place.

During that time, finance in a sense shrinks, declines. The high period, the growth and so on of the previous decades in a sense comes to an end, and finance begins to be controlled in important ways. That’s when Glass-Steagall is introduced.

JAY: Yeah. I mean, this is, I think, a really significant part is that with the crash, so much triggered by all the financial speculation, you can say FDR is able to assert the class interests of the whole capitalist class and system and say, we can’t let you guys go out of control, ’cause you’re going to sink the whole system. And they are very afraid of a rising working-class socialist movement in the United States and globally. So there is the ability to restrict it for the sake of the system. I mean, the reason I’m saying that, it’s important, ’cause obviously a little later on, where we are now, it’s not so clear anyone’s going to do that.

LAPAVITSAS: That–I mean, to a certain extent this is undoubtedly true. It happened, basically. But we must bear in mind also the reality of the ’30s. It isn’t simply what Roosevelt did and so on. It’s also what’s happening, in a sense, at ground level, that basically capitalism was collapsing. It isn’t simply–I mean, this is a really profound crisis, where the links between businesses, the ability of business to reproduce itself is in serious doubt. Unemployment is huge. The thing doesn’t work. So finance is placed under control partly because of the ideology of putting this part, this aggressive part of the system under control, but also because people are fumbling and trying to find a way out of this chaos.

Now, the real controls, though, and the real period of [incompr.] finance comes with the war, when the banking system is used to finance the U.S. war effort in other countries, the war effort of other countries. And then we emerge out of the war with the United States effectively having won it economically, if nothing else. It has recovered from the crisis of the ’30s. The banks are now under control. This is a system of controls over banks. Glass-Steagall is in place. The battery of other controls on interest rates and on the lending and other functions of banks are also in place. And big business is also different. This is a kind of business that engages in profitable productive activities on the basis of mass production and mass consumption. We entered a period of 25 or so years–the most extraordinary period in the history of capitalism, basically–of rapid growth and so on, in which finance remains controlled.

JAY: What was it? A car in every garage, a chicken in every pot, refrigerators, and–

LAPAVITSAS: You know, all that. All that.

JAY: –all the consumer appliances and–.

LAPAVITSAS: All that, which is quite unique in the history of capitalism.

In a sense, finance grows and gradually gets rid of all those loans they made to the state to fight the war. But it’s under control. It’s under control. And that cannot have been a bad thing, because, as I say, growth during that period is unprecedented.

But, of course, capitalism never remains static. Big business grows. Big business begins to go abroad. Big business begins to change the way it works. The world begins to change. And then the 1970s come, and a massive crisis happens in the ’70s.

JAY: Please join us for the next segment of our interview on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

“Costas Lapavitsas is a professor of economics at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London and was elected as a member of the Hellenic Parliament for the left-wing Syriza party in the January 2015 general election. He subsequently defected to the Popular Unity in August 2015.”