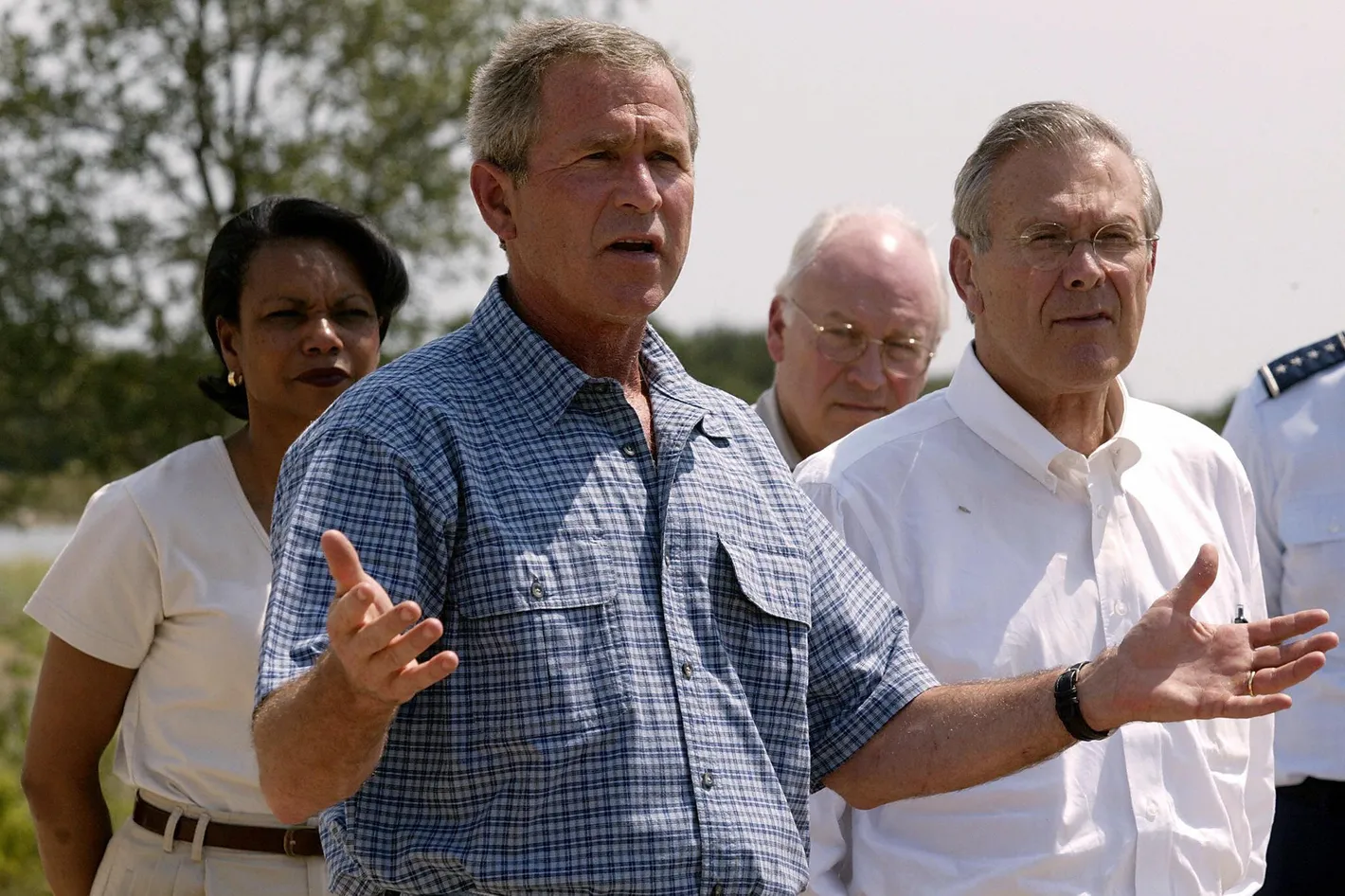

Why Didn’t Bush Cheney Attack Iran and Can Obama Make and Sell a Deal – Gareth Porter (pt 3/3)

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on March 18, 2014. Mr. Porter tells Paul Jay that the American security state was and is against war with Iran, but if Obama doesn’t break with the false narrative about Iran’s nuclear program, he may not be able to seal a deal.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And this is Reality Asserts Itself.

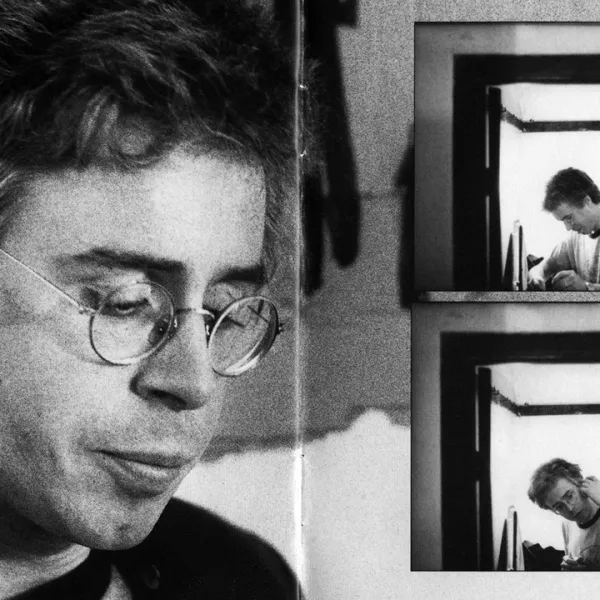

We’re continuing our series about Iran, its nuclear program, the Americans, and the Israelis, and a new book by Gareth Porter.

And Gareth now joins us in our studio.

Thanks for joining us, Gareth.

GARETH PORTER, INVESTIGATIVE JOURNALIST: Thank you very much, Paul.

JAY: So Gareth is a historian. He’s an investigative journalist. He covers U.S. foreign and military policy. His latest book is Manufactured Crisis: The Untold Story of the Iran Nuclear Scare.

So we’re going to pick up where we left off. And essentially at the end of the last segment I was asking the question, if, as it seems true, that Dick Cheney, vice president, and President Bush were fairly intent on attacking Iran—and in earlier segments we talked about a document called Project for the New American Century, written and signed by many neocons who made up the Bush administration, and it clearly laid out it’s time to assert American power—Iraq, Syria, and with the real prize being regime change in Iran and the need for a manufactured narrative to rationalize all of this, get American people on board, especially after a failed Iraq War—how do you get people ready for another one? Well, I guess you need a mushroom scare.

Gareth, I guess that more or less says it, does it?

So why didn’t they get their war?

PORTER: They didn’t get their war, because there was very strong built-in resistance on the part of the national security state in the United States, particularly the military and the Pentagon, to getting into a war with Iran. And I think this reflects the reality that Iran really is capable of doing damage to U.S. military assets in the region.

U.S. bases in the Middle East are extremely vulnerable to an attack by the Iranians. Particularly, U.S. naval vessels in this narrow gulf that they have to go through are vulnerable to—.

JAY: And, at the time, tens of thousands of American troops in Iraq.

PORTER: And U.S. troops in Iraq, of course, yes. That was the third leg, I think, of this triad—the bases, the troops in Iraq, and the fact that U.S. ships in the gulf were easy targets for anti-ship missiles that the Iranians have really worked very hard on—they have some very good ones. And the Navy in particular knew that its ships were extremely vulnerable, and I think they, more than any other service, were extremely wary of any policy that involved the potential for war against Iran.

And that’s why I think you had William Fallon, when he became the head of CENTCOM in 2007, was extremely keen on making sure that the Bush administration was not able to go to war. And I wrote a story at that time, the first time that anyone had written about Fallon’s commitment to essentially ensuring that there would be no U.S. war against Iran.

JAY: And there must have been a feeling, you know—what is it?—fool me once, fool me twice, shame on me. The American military also was sucked into the Iraq War based on false intelligence. I’m sure many of them were in on, you know, all the manipulations that took place.

PORTER: Well, Paul, I would say Iraq is a bit of a different case, and that’s because the lineup of interests on the part of the military services was a bit different. It’s true the Army was very much opposed to Rumsfeld’s approach to Iraq, the idea that you’d send in a small contingent of troops, relatively small contingent of troops, and use air power as the main way of battering down the government of Saddam Hussein.

JAY: Yeah, I’m not so much—I’m saying more a lack of belief in the intelligence that would have been offered to justify the war in Iran.

PORTER: Well, I don’t think the military ever really gets involved in the question of the use of intelligence. The real question for them is: Is this a war we want to fight? Is it a war we will be able to fight or not? And for the Air Force, what I wanted to say is the Air Force was extremely bullish on this war because—

JAY: On Iraq.

PORTER: —they knew—on Iraq—they knew that this was going to be an Air Force war, essentially. It was going to be essentially a war that would rely on air power to get rid of the Saddam Hussein regime. So they were in favor of it. But the Army was not. So that was a more complicated setup of politics within the Pentagon and the JCS on that.

JAY: I guess I’m just suggesting that in the professional both foreign policy and intelligence community—and we know, as we head towards the NIE, what do you believe that comes through John Bolton?

PORTER: Right. And, of course, you’re right, as far as the CIA is concerned: on Iraq, George Tenet was clearly complicit in this war policy and skewed the intelligence, made sure that the intelligence was going to support the policy.

When it came to Iran, I think we see some of the same problems reasserting themselves. Tenet, of course, was no longer there. It was Porter Goss who was CIA director in 2004, in mid to late 2004, after the documents which were passed on from the Israelis originally, through the Mojahedin-e-Khalq, to the German intelligence, and then on to the CIA became a factor in this equation. And from everything that I know, everything that I’ve seen, Porter Goss and his top lieutenants knew perfectly well these documents came from the MEK. They had every reason to distrust them. But they didn’t tell Colin Powell, certainly, and they didn’t tell other people in the administration that that was the case. They were playing a game with the vice president’s office, with the people in the Pentagon, and, of course, with John Bolton and the Israelis, to make sure that the narrative would survive, that is, the narrative that they were creating with these documents would survive.

JAY: But it doesn’t succeed. There were military retired generals writing in The Washington Post saying this makes no sense.

PORTER: Well, remember first of all that 2004 is still a few years before the Bush administration really expected that they would have to use force in Iran. First of all, they had to consolidate their control over Iraq before they could move on to Syria and then Iran. So they weren’t ready to do it yet. They were looking ahead two, three years.

So it’s really 2007 when this issue becomes a live issue. By then they knew Iraq was not going well, and they knew that they had to make some decisions about Iran, because, you know, the situation there was still problematic from their point of view. So they basically—that’s when the vice president began to make a proposal that the United States retaliate for some kind of incident in Iraq that they could blame on the Iranians which would result in American casualties. And that was the game plan that he was advancing within the national security state as a basis for getting at Iran.

Now, you know, of course, he expected that it would mean that there would be escalation. We could then take shots at the nuclear program, and, indeed, you know, hit Iran where we wanted to hit them, which was their military power and their economic power. But that’s—wasn’t acceptable to the Pentagon. They simply sat on it and made sure that it wouldn’t go anywhere. They said, well, where is this going to lead? And, again, I—.

JAY: Well, we’re not going to fight on three fronts.

PORTER: Exactly. They had no intention of doing that.

JAY: Now, take a—what do you make of the way mainstream media—I mean, I guess this is a bit of a softball question, ’cause you’ve been one of the few on this—but after Iraq it kind of boggles the mind that you could have such, you know, supposed intelligence about Iran, and it gets treated with the same—like, it’s gospel the way the Iraqi intelligence was. It’s really kind of remarkable.

PORTER: Yeah. I mean, what happened on Iran, I think, gives the lie to the idea that the news media in this country were really trying to do the right thing, you know, learning the lesson of Iraq and so forth. The fact is that their first commitment was to maintain their ties with the people who had the power in the national security state. And because the news media simply does not want to be an adversity position—adversary position, I should say, to the national security state, they go to great lengths to avoid that. And I think this was one of the tests of that principle, that they had no intention of questioning what was going on with regard to these documents supposedly from an Iranian covert nuclear weapons program.

JAY: I mean, Sunday after Sunday morning television, for years we have heard various people from both the Bush administration and then the Obama administration say they have a nuclear weapons program. No one ever says, what evidence is there of it, what about your own intelligence estimates that said they don’t have a weapons program, week after week. It’s all, like, this built-in assumption, the idea that Iran is an existential threat to Israel. It’s widely debated in Israel; it’s taken by the media and the politicians here as an absolute fact.

PORTER: Right. And I think that this particular instance, this whole episode of the so-called laptop documents, the documents that were supposedly on the laptop of an Iranian scientist and were somehow purloined and gotten out of the country, is a perfect illustration of just how unwilling the commercial news media are in this country to ask questions, to fact-check, much less to actually investigate—what are these—what was the origin of these documents? They were always extremely mysterious. Nobody was really telling a full story about how they had been obtained. It was whispered in the ears of The New York Times and maybe one other newspaper that, you know, these came from a purloined computer, but generally speaking they were very mum about this story. And it should have been a cause for skepticism, obviously, for any legitimate newspaper reporter or—.

JAY: I mean, it easily could have all happened again.

PORTER: Exactly.

JAY: The Iraq thing could have all happened again—nonsensical intelligence and war.

PORTER: I’m ready to argue that what happened with regard to these documents is in fact a direct parallel to the Curveball affair, that is, the bioweapons lab story told by this Iraqi in Germany, which resulted in Colin Powell using this as the centerpiece for his talk at the United Nations in 2003 to justify an invasion of Iraq.

JAY: Okay. Let’s bring it up to date. For most of the Obama administration, President Obama, once he was in office, repeated more or less the same stuff we were hearing during the Bush administration. I say once he was in office because I’ve been saying from the beginning the one thing that Obama differentiated himself from—and Biden as well—during the election of ’08: they did have a fairly rational take on Iran. Obama at one point was saying—somebody, one of the debaters was saying, you know, Iran’s going to become this power in the region if we don’t do something about it, and I think Obama specifically said, well, it’s a little late to say that, ’cause if you didn’t want them to do that, you shouldn’t have invaded Iraq.

PORTER: Well, of course, Obama was running as an antiwar candidate, and he knew that he needed to—.

JAY: Well, an anti-Iraq War,—

PORTER: Well, an anti-Iraq War candidate.

JAY: —not antiwar.

PORTER: That’s right. But the idea was to appeal to the antiwar—.

JAY: ‘Cause he had his war. He had his Afghan War. Yeah.

PORTER: He was appealing to the antiwar sentiment in the country,—

JAY: Yeah.

PORTER: —to that constituency of the Democratic Party and beyond.

JAY: But Biden even went further. In the last election, the same thing came up in the vice presidential debate, and Biden said very clearly, said, look, we know they’re not weaponized, we know they’re not heading right now towards a weapon. Cool down.

PORTER: Right.

JAY: You know, he said if they ever do try to do this, we’re going to know it in plenty of time.

PORTER: Right.

JAY: Everyone should just take a step back. So there was a shift that they understood in terms of American national interest and the desire to project American power in the world, and this is part of this Asia pivot thing. They didn’t want a war with Iran. And now we’re seeing that policy come more to fruit, though it’s interesting even to look at the media media now. You know, Iran has a bomb, Iran has a bomb. Now all of a sudden Kerry says the Iranians are cooperating. Even the media has kind of toned down everything as part of the—

PORTER: But, Paul, remember, you know, definitely Obama did not want a war, a conventional war with Iran, but one of the first things he did when he got into the Oval Office was to start talking to the cyberwarfare people who were working hand-in-hand with Israel to plan a cyberattack against Natanz, the Iranian enrichment facility, which would become the first ever national cyberattack against another nation which would actually result in destruction of infrastructure, that is to say, the centrifuges which were affected by this attack. So, I mean, you know, clearly he was willing to carry out warfare against Iran, just not the conventional war.

JAY: Well, I think—add one thing to that, which you and I have talked about before, is the sanctions are a form of warfare.

PORTER: Indeed. Of course. Right.

JAY: I’m not in any way suggesting Obama’s policy wasn’t containment, weaken Iran, you know, try to undermine any kind of influence Iran has in the region, and even regime change if possible, but through the sanctions. I’m sure all of those objectives are also Obama objectives, but not war. And that differentiated himself, I think, and still does so far, from the Saudis, and certainly from Netanyahu in terms of the Israelis.

PORTER: He wanted to put pressure on Iran, and he would do so both by cyberwarfare and by sanctions, I think it’s fair to say, as well as, by the way, exploiting the threat of an Israeli attack. There was a lot of that going on in 2009 and 2010 as well.

JAY: Okay. So let’s just again—where we are now. It certainly seems, would you agree, that if Iran does make these kind of—to me, based on what I know, they’re almost symbolic. If one does believe the Iranians don’t have a weaponization program, then by agreeing to the sort of things that P5+1 are asking for, it’s not that big a give for the Iranians, as long as they create enough defense of their sovereignty to keep some level of enrichment. So it sounds to me like the Iranians can do what P5+1 wants. So it sounds like there’s a deal to be had here.

PORTER: It’s more difficult than it seems at first glance. When you talk about what the Iranians need to do to defend their sovereignty, in a way it’s not just their sovereignty. It’s national dignity. It’s the—the problem being that there’s a very powerful public opinion in Iran, which represents a majority of opinion in the country, as far as, you know, past studies of public opinion there have established, that really believes that if Iran dismantles, you know, thousands of centrifuges, that that is bowing down to a demand, an unnecessary and an illegitimate demand by the United States. So that’s the kind of thing that I think causes serious political problems for any government in Iran. I think that that—.

JAY: Can Obama sell the deal without it?

PORTER: Well, Obama can sell the deal if he is willing to break with his past acceptance of this false narrative. But I think he would have trouble within that narrative selling it. I think that’s the problem. And that’s why I’ve suggested that I think the—.

JAY: Just to remind everybody and make sure I have it correctly, the number of centrifuges, according to the Israeli-American position, leads to the conclusion, with that many centrifuges you can produce more than you need for a civilian program, which means you’d have the capacity to weaponize. So they want way less centrifuges. That’s their argument. Is that true?

PORTER: Well, I mean, in the first place, there’s a difference between the 18,000 or 19,000 centrifuges total that they possess and that are in the location that—or the two locations we’re talking about and centrifuges that are hooked up and operating. At least 8,000 of their centrifuges are not hooked up and they’re not operating, so they’re not going to produce uranium, enriched uranium, and they’re not [crosstalk]

JAY: But the argument is: if they wanted to, they can hook them up.

PORTER: They could hook them up, but it would be immediately known. And so you would have many months of advance notice. And it’s clear they’re not going to do that. I mean, you know, it’s ridiculous to say they’re going to hook them up and are going to start a process which would take months for them to conclude.

JAY: Alright. So just quickly, to conclude, we’ve always said this has never really been about nuclear weapons, it’s more about the geopolitics of the region. Israel does not want such a powerful Iran. It helps Hezbollah. It can help Hamas. They do not—the Saudis do not want a powerful Iran in the region for all of their reasons. And it looks now like the Americans, if they—they can envision within American interest a deal with Iran, which is not the Saudi and Israeli interest.

But it does lead to the conclusion that the Saudis and Israelis, especially the Saudis, from what I’m hearing, might do anything they could to kind of blow this thing up.

PORTER: Well, I certainly agree with that conclusion. I mean, there’s no question about it that the Saudis and the Israelis both would do whatever they can, whatever they feel they can get away with, to blow up these negotiations.

But I’m not nearly as optimistic (I think I would use that term as I think you just expressed it) about the sort of breaking the past framework, or paradigm, if you will, by the Obama administration. The Obama administration, yes, they want to reach an agreement, I agree, but they are not breaking with the larger framework in which Iran is the enemy, is the other in the region. They still plan to attack Iran as, you know, a supporter of terrorism, official state supporter of terrorism, and as a troublemaker in the region, and as, generally, a problem that has to be solved by some kind of alliance with Israel, and perhaps even the Saudis to some extent, although I agree with you that that’s a very troubled relationship, and some sort of a containment of Iran. That’s still going to be the framework. So I think we’re still stuck in that mode for the foreseeable future.

JAY: Okay. Thanks for joining us.

PORTER: Thank you.

JAY: And thank you for joining us on The Real News Network. And don’t forget Gareth’s book is Manufactured Crisis: The Untold Story of the Iran Nuclear Scare.

So thanks again for joining us on The Real News Network and Reality Asserts Itself.

“Gareth Porter is an American historian, investigative journalist, author and policy analyst specializing in U.S. national security issues. He was an anti-war activist during the Vietnam War and has written about the potential for peaceful conflict resolution in Southeast Asia and the Middle East.”