An Occupier’s Peace or a Just Peace – Shir Hever on Reality Asserts Itself (pt 4/4)

This interview was originally published on July 13, 2014. Mr. Hever says the occupiers always want peace – a peace that strengthens the status quo.

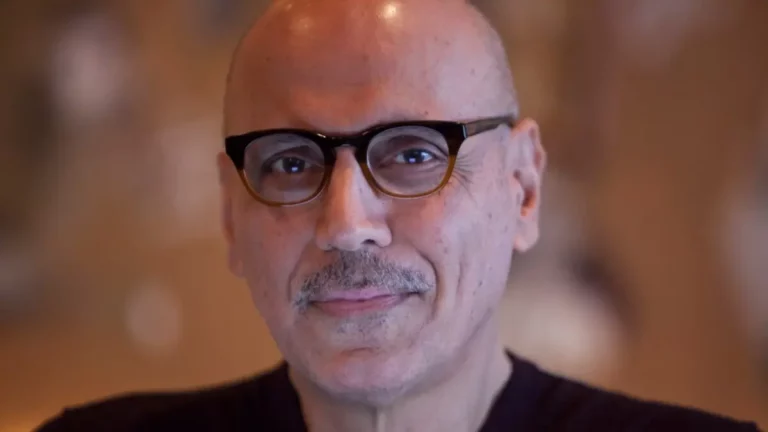

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. This is Reality Asserts Itself with our guest, who now joins us in the studio, Shir Hever.

Shir is an economic researcher. He works in the Alternative Information Center, a Palestinian-Israeli organization active in Jerusalem and Beit Sahour. He’s now working in Germany on his PhD. He’s visiting us in Baltimore. His last book was Political Economy of Israel’s Occupation: Repression beyond Exploitation.

Thanks for joining us again.

SHIR HEVER, ECONOMIST, ALTERNATIVE INFORMATION CENTER: Thanks for having me.

JAY: So if you’re going to talk about what the future might look like, what a peace, if possible, might look like, you’ve first got to talk about, well, who actually wants peace, and on what basis do they want peace? There’s a lot of people–I shouldn’t say a lot of people–there are a few people in Israel who are doing extremely well out of the current situation. You know, there’s a stratum of multimillionaires and billionaires, a political stratum. I mean, why would they want anything other than what they got?

HEVER: I think the vast majority of the Israeli public wants peace. But a famous German military thinker, Clausewitz, has once said the occupier always wants peace. Peace means the status quo. That’s why Palestinians don’t call for peace, they call for a just peace. And that’s also why the Israeli peace movement has collapsed because the peace movement had this kind of idea that if Palestinians would be offered peace, they would just accept that the current situation will continue. And, of course, that’s a completely false premise.

But there are, of course, people in Israel who do have an incentive to end the occupation and to end the injustice. A lot of Israelis are suffering because of the massive cost of security that is needed to repress the Palestinians. I would say the majority of Israelis are losing in their standard of living because of this continued repression of Palestinians, because of the continued conflict. So they have a real interest even in a just peace, but their voices are not heard and they cannot be heard within this kind of colonial system, which is dominated by those elites who are actually profiting.

JAY: So talk a bit about the elites because it’s a very small group that own the dominating, commanding heights of the Israeli economy.

HEVER: Yeah. And I would say the major forces that push Israel in this direction of continued conflict and continued occupation are actually outside of Israel. These are the forces–the U.S. government and right-wing groups within the U.S.–that fund the most extremist and violent political movements inside Israel. Sheldon Adelson in the U.S. has opened up a free newspaper in Israel in order to make sure that Netanyahu keeps winning the elections with a massive investment that no one on the other side can match. So that sort of support makes sure that the hawks continue to dominate the political structure.

Sure, there are also Israeli security companies and military companies that are very powerful and very influential. In fact, there was a meeting in 2011 of 80 of Israel’s biggest capitalists but not from the security sector, which said, if Israel will continue on this path, we’re going to get to the situation of South Africa, we’re going to be boycotted by the world, we have to do something. They had this emergency meeting. But they couldn’t actually do something. It shows that even capital has its limits. They couldn’t find a way to convince the government to act differently because there’s just no historical precedent for that. There is no historical precedent of a colonial power which just stops in its tracks and says, this is wrong, we should allow these people freedom and equality.

JAY: Would you say if outside of the security-military-industrial complex, if you will, the rest of the majority of big capital would actually like to see a resolution of this?

HEVER: Yes, yes. And they’ve tried a couple times to fund their own candidates for prime minister and spent a lot of money on that. The public didn’t vote for these candidates. The public wants a strong leader that can say–a sort of security person who can say–I will be a representative of your national pride, I will make sure Israel is safe, I will fight Iran, and so on. And when somebody says, if we end the occupation it’s actually good for the economy, this sort of argument doesn’t get–.

JAY: But if their heart was really in it–and they being these other big capitalists–I mean, they could match Sheldon Adleson and they could have their own TV stations and their own newspapers. I mean, they could really go at it. Is their heart really in it? They’re doing so well the way things are.

HEVER: I think they estimate that if they do that, people will not see that, won’t watch that television or will not read the newspaper. And they’re right because people don’t like to read that they’re in the wrong, and that things have to change, and that political power has to be shared. They don’t want to read that.

JAY: Alright. So let’s–if you had a platform in Israel–and I think it’s pretty difficult for you to have one; given the state of the mass media in most of the West, it’s hard to get any kind of platform. And you’re always welcome here, of course. But what is a model that if you could even think ten, twenty, thirty years out, if you were going to try to create a model that would be, one, sellable, not just just. I mean, you can imagine a just model, which is pretty straightforward. It’s a Democratic, single secular state and everybody gets to vote and it’s, you know, a modern country. But right now that’s not a sellable proposition. So some people, like, just as example, some people have talked a possible federated state, where you have a province or a state within a Federation which is primarily Jewish. Hebrew would be the language. You would have another one, another state, which is primarily–Arabic is the primary language, and so on, or some configuration. You must have thought about this. What might be possible?

HEVER: It’s not only that I’ve thought about it, that this is also almost an obsession, but not just for me, but for political activists, for leftists for years.

But I want to answer you in two parts. The first part, I have to say, again I have to be very sensitive to my own position of privilege. Being an Israeli Jew and saying well, this is the solution is not going to work, and it shouldn’t be, it shouldn’t work. Palestinians should not get their solution from some Israeli. They have to come up with their own platform for political change. And therefore, I have to be very careful in how I answer that sort of question.

Having said that, let me tell you what voices I hear from my Palestinian friends about what they’re saying. And among these voices, you can hear a lot of those ideas of a federation, a confederation, two separate states, three separate states, one democratic state, joining with Egypt. You can hear a lot of interesting ideas. But the voice that comes out the clearest in the last few years is the voice that says, we don’t care about that. All of these ideas are legal demarcations, are some kind of–where you put the border here or there. That’s not important. The important thing is to talk about rights, talk about how we have the right to move wherever we want, to say whatever we want, to have a government that represents us, to organize, to practice our religion, to trade freely. That’s what it means to be free. And then it doesn’t matter so much exactly how many borders you’re going to stretch across this territory. If we’re practical about it, historically Palestine is a country that was divided by the UN, but in fact there has never been a Palestinian state there. There’s always been one powerful force of Israel and some areas that were temporarily held by Egypt and Jordan, and then Israel occupied these parts as well. Now we have a situation in which there’s one state under Israeli domination with a population of 12 million: 49 percent Jews, 49 percent Palestinians, 2 percent others. And it’s an apartheid state.

JAY: In that math, you’re including occupied territories.

HEVER: Of course. Yeah. This is where Israel is sovereign. This is where the Israeli currency is accepted as the only legal tender.

JAY: What I’m getting at, and I don’t–you know, obviously this must get talked about a lot over there, but it doesn’t get talked about so much over here–if there’s going to be rights, there’s going to have to be at some point some kind of buy-in by enough Israeli Jews to go along with this, I mean, unless you think there’s going to be some military defeat of the Israeli state, and it’s hard to imagine that right now. Even if the American policy was to significantly shift, you still have a mass of Jewish-Israeli public opinion that is where it is. I mean, it’s in not a very good place. There’s got to be some kind of understanding of how that’s going to be dealt with to create a model that’s at least the next step.

HEVER: There’s this famous British general that once said in Zimbabwe, whatever happens, we have machine guns and they don’t. And they lost. So the military defeat is not so unimaginable, but, of course, it’ll be further down the road. It’s not going to be in the next few years.

I think the fact is that a Jewish state is not sustainable. It’s a concept that doesn’t fit the 21st century. It barely fits into the 20th century. It’s a racist idea.

JAY: Without question it’s a racist idea, but it’s there. I mean, so is the Iranian state a racist idea. So is the Pakistani state a racist idea. I mean, there’s no reason why a Jewish state is more racist than an Islamic state. What’s the difference?

HEVER: Well, I think is a difference between a theocracy and a racist state, because in Iran you can always convert to Islam, right? And in Israel you cannot convert to be a Jew if you’re Palestinian.

JAY: You can’t?

HEVER: There is a theoretical possibility, but in practice no court of rabbis would let you do it.

JAY: But even if you could, it doesn’t change the fact that it’s a religious-based state. It’s an Islamic state in Iran and Pakistan and some other places. What’s the difference? I mean, why is it so different?

HEVER: The difference is that you were born as Jewish or not Jewish, that it’s imprinted.

JAY: Yeah, well, there’s many Jews born in Iran, but the state is Islamic.

HEVER: Yeah, no. I’m saying that the law is a racist law. The law, it says if you find that your grandparent is Jewish, it almost doesn’t matter what you believe and what kind of lifestyle you have; you can get an Israeli citizenship.

JAY: It’s not that different in Iran. If you have Persian blood–you can have been born in Canada, for example–I have a friend who was born in Canada, never been to Iran. She went to Iran. They considered her Persian, they considered her Iranian.

HEVER: Persian blood from 2,000 years ago?

JAY: Doesn’t matter. If you’re Persian, you’re Persian.

HEVER: Okay. Well, yeah. I’m not an expert on Iran. I understand.

JAY: There’s bloodline there. I mean, I’m not saying–I’m just–there’s differences, of course, but I’m saying it’s a secular–.

HEVER: But I’m also not saying that Iran is a sustainable political model either. But I’m saying that–.

JAY: I don’t think–I agree; I don’t think it is.

HEVER: Yeah. So I’m saying that a Jewish state will collapse. It’s a question–it’s a matter of time and it’s a matter of how. When you said military defeat, I’m going to say there’s another option: there’s also political defeat and a cultural defeat.

JAY: Well, I was about to get to that, ’cause then you get to the campaign for boycotting, disinvestment, and sanctions. It’s clearly having some influence. It’s hurting the Israeli economy. If it was stronger, it could precipitate more self-interest in some kind of change in Israel. But don’t you then still have to have–okay, then what does that look like? ‘Cause if you get to a point of real rights the way you’re talking about, this can’t be a Jewish state anymore.

HEVER: Exactly. Yeah. It cannot be a Jewish state. It’s going to be–I mean, even if there will be a separate Palestinian state according to what we call the two-state solution, then the battle will continue. The struggle for equal rights in Israel will continue, because Israel cannot be a Jewish state; it has to be a state for all its citizens, one way or another. And the way that this defeat comes, it comes very suddenly. And, of course, the model is South Africa, where one week before apartheid collapsed, 90 percent of white people in South Africa supported apartheid. One week after apartheid collapsed, they all say we were always against it. And the Israeli minister of justice, Tzipi Livni, just said a couple of weeks ago, in response to the BDS movement, she said, I went to South Africa and spoke to some Jewish people there about their experiences from this era of the fall of apartheid, and the main thing they told me is it came unexpectedly, it came suddenly. There is a moment in which you lose courage, you lose your faith that you can continue to repress other people forever. And that moment may not be as far as we believe. I’m hopeful.

JAY: I think you would–personally, you’d have to see some pretty serious revolutions in the Arab world, which is not out of the question. But if Israel was then looking at revolutionary progressive governments actually willing to do more than lip service in support of the Palestinians, that might change the equation. But right now I can’t see it. With the current Arab regimes, Israel does not have much to fear.

HEVER: Well, I think the fact that Israel doesn’t have much to fear from external forces actually makes it easier for the Israeli public to realize that you cannot distract from the main question about what kind of apartheid regime you have inside. And as long as there is a big enemy–that’s what Netanyahu always tries to do; he says the problem is Iran, so let’s not talk about what’s happening here.

JAY: An age-old practice. If (and in my mind it’s only a question of when) the world heads back into a massive economic crisis, triggered either by finance or something else, how would that affect the politics in Israel if you’ve started getting unemployment of 15, 20, 25 percent, 1930s style economic consequences?

HEVER: Well, I think it’s not a question about how deep the crisis is; it’s a question about how it is perceived. Economics is not like physics. It’s not–you cannot measure the red line that makes a society collapse. It’s all about how people think about the situation. So as long as people–I mean, there was the Arab boycott against Israel for many years, and it only started to fall apart with the Oslo negotiations. And the Arab boycott in many ways was much more comprehensive and effective than BDS, but it was not perceived in Israel as a real problem, because it was seen as a sort of incentive for Israel to invent itself and get their goods elsewhere.

But now we’re in different situation. Now every time a performer, an artist, decides not to make their performance in Israel as a political statement because they reject apartheid, it has more impact on the Israeli public than a loss of millions in exports. So that kind of impact makes Israelis think, maybe we should go to other countries. There is actually a strong immigration of–.

JAY: But I’m talking–my question wasn’t about BDS. My question is, I think it’s just a matter of time. I don’t know whether it’s two years, five years, or ten years–I doubt it’s much longer–where the kind of financial shenanigans that triggered the 2008 crash repeat themselves in a far more profound way and we could be seeing unemployment rates of 1930s style level of unemployment around the world. And I think everybody that’s interested in, you know, the well-being of people had better get their heads around what are we going to do when that day comes, ’cause it could be sooner than later. How might that affect Israel?

HEVER: Well, I agree with you that this sort of crisis seems imminent, but I’m quite worried that it will have exactly the opposite effect on Israel, because one of the things that the government or the media in Israel are saying whenever there’s a question about how long can we sustain the occupation, they say, well, look at Greece, look at Spain; things are bad elsewhere, so we’re not so special, so we can continue and not address these acute questions. So if the crisis is global, then it makes it much easier for the Israeli government to just brush it aside.

JAY: So right now the BDS movement is having the most effective thing–of those people that want to see a change in Israel, BDS is the main game at the moment?

HEVER: Well, I think there’s no other movement that has a, really, horizon and an imagination of how they’re going to move on to the next step. BDS is–BDS in itself cannot change anything. It’s very important to say. BDS in itself is a way for the international community to express solidarity, for people around the world to show that they are watching what’s happening in Palestine and want to take part in that. But there’s no level of BDS that makes Israel forsake their policies. It comes from the Palestinians who are fighting for their rights and being supported by BDS.

But BDS has a profound impact on the Palestinian struggle, too, because the main thing that Hamas are saying all the time: they’re saying the international community has forsaken us, they don’t care about us, so we have only ourselves to trust to free ourselves from the shackles of occupation. And the BDS is saying, no, there is somebody paying attention, which means that there’s an alternative to the violent path and to the military struggle.

JAY: Okay. Thanks for joining us.

HEVER: Thank you.

JAY: We’re going to continue this discussion with Shir in another series sometime probably in a few weeks or a few months. But for now this is Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

“Shir Hever is an economic researcher based at the Alternative Information Centre in Jerusalem. He is the author of The Privatisation of Israeli Security (Pluto, 2017) and The Political Economy of Israel’s Occupation (Pluto, 2010).”

Please have a new conversation with Shir Hever