Identity and Collective Denial – Lia Tarachansky on Reality Asserts Itself (3/3)

This interview was originally published on December 19, 2014. Ms. Tarachansky says Israel is ripping itself apart and fascism is celebrating in the ruins.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network and welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself.

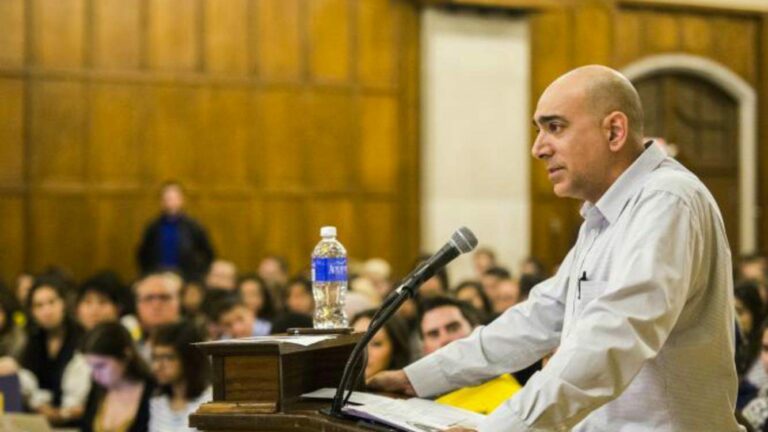

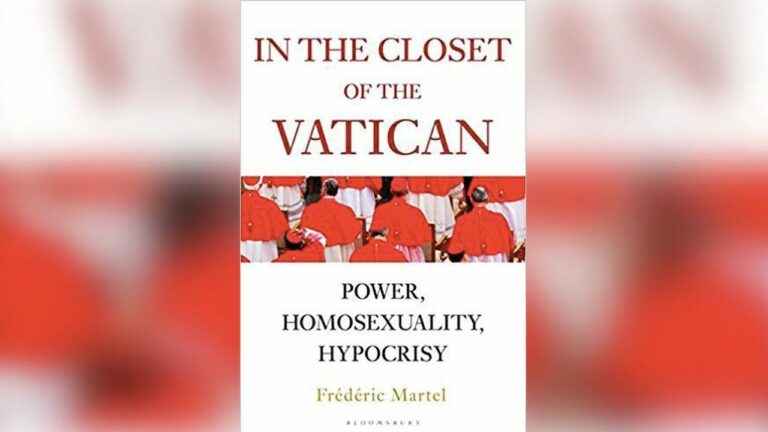

We’re continuing our series of interviews with Lia Tarachansky. She was The Real News’ Palestine-Israel correspondent. She’s now the director of On the Side of the Road, a new documentary about Israel’s biggest taboo, the denial of what happened in 1948. And she now joins us in the studio.

Thanks for joining us. Again.

LIA TARACHANSKY, ISRAEL-PALESTINE CORRESPONDENT, TRNN: Thanks for having me.

JAY: So we’ve been talking about identity. We’ve been talking about Lia’s own kind of arc of her own identity. And you really should watch the other segments, because this then will make a lot more sense to you.

So let’s talk about Israeli identity today. I’ve been to Israel three times, once when I was, I guess, about 14, and my sister had gone, and she was living on a kibbutz, and my father had just died, and I went there. And I was astounded at how I felt denigrated for the first time. As a Jew in Canada, I’d felt a little bit of it, but not much. But I was amazed: on the kibbutz I was treated like a zero.

TARACHANSKY: Why?

JAY: I wasn’t–what’s the term now?

TARACHANSKY: Sabra?

JAY: Sabra. And I just–it was so much to me that I wasn’t the born–.

TARACHANSKY: Explain that, though.

JAY: Well, this is if you’re not born in Israel. Explain it to me? I mean, I just felt that they was–

TARACHANSKY: You’re an outsider?

JAY: –not interested in me. And they were trying to persuade me, maybe partly ’cause I hadn’t bought into the narrative, or they were trying to say, no, no, no, you have to have Israel, ’cause all the Jews are going to have to come here someday to save themselves. And I hadn’t–I mean, it’s not that I hadn’t experienced any anti-Semitism, but not–my identity was Canadian, not–and for those of you who are watching, you know I’m a dual citizen, and now I live in Baltimore, and so on and so on.

TARACHANSKY: So you’re trying to sell your audience the narrative that at the age of 14 you had a political analysis.

JAY: No. I had an experience, just an experience. And I knew nothing going into it. I had the vaguest notion of what Israel was. It wasn’t even on my radar. I went back again for a film festival, and then I went back again only three, four years ago, and over the arc of it, with just a little bit of that experience, I was just blown away at the overtness of the racism now. It would have been a bit like during slave days the way whites would have talked about blacks, like, without any sense that you should even mitigate your language.

How does it get to that point? What is it about–where, in terms of the evolution of the Israeli identity, does this absolute overt racism come from? ‘Cause in the early days of Israel, I don’t know, maybe some people certainly thought something like it, but they sure wouldn’t have said it like that.

TARACHANSKY: Yeah. As an Israeli Jew, this is the stuff that keeps me up at night. Also, literally there’s /laʊ/ a lot of–I’ve been robbed of my anonymity on many fronts. And there’s a lot of it that creeps into your life.

But the way I understand it is, like, it’s a combination of two things. I think what’s–you’re seeing on the streets today in Israel, with the constant street-level violence and racism and attacks on anyone who questions anything, attacks on leftists, attacks on Palestinians, that it is the natural conclusion of the Zionist idea coming to its most screeching, screaming peak in having to defend itself. And this is part of the ethnocracy we’re talking about. This is the natural conclusion.

What is Zionism? Zionism is the idea that the Jews have a homeland in historic Palestine, in the ancient land of Canaan. That’s spiritual Zionism. Practical political Zionism means that the Jews have more right to be on this land, and then they must be a Jewish majority on this land. How do you do that in a place that was never empty, in a place that, first of all, was already home to competing national movements, that was already engaged in very rich and ancient culture, both from the Ottoman Empire and the Arab invasions, and was–this place is the crossroads of human migration. How do you come to this place, which is in the middle, between Asia, Europe, and Africa, and you say, no more, here’s our walls, and we’re building a wall with Syria and Lebanon and Jordan and Egypt, and no one but Jews can get in? As I’m sure you know, there’s no immigration to Israel unless you’re a Jew. You can’t immigrate, you can’t come in. It’s a state for Jews and only Jews, and we will eventually get rid of anyone who is not a Jew. That is political Zionism today.

And the disparity between understanding that this is what it is here in North America as I’m touring my film and I’m realizing how few people understand what it is and the reality on the ground, this idea playing itself out to its screeching peak, is–the disparity is astounding and playing itself out is incredibly violent and intense. And so, today, if I was to talk to you on the bus or I was out walking down the street with you and I was saying all these things, there’s a very good idea that we would be beaten by the time we get to the end of the street, because there is now so much threat to that idea surviving. So that’s the first thing.

The second thing is colossal disappointment over the so-called peace process finally completely dying. There was a little bit of hope with Obama, Kerry, a little bit of hope with George Mitchell. It was kind of like no one really believed that they would do anything. A lot of people said, well, at least something’s happening. America, having taken the side of Israel on all of the peace negotiations, having put all its capital on the side of the Israeli negotiators, all of its weapons on the side of Israel’s negotiators, and then sat in the middle calling itself the unbiased mitigator in this negotiation, which we’re doomed to end, gave us a false sense of hope. It has built endless institutions in Palestine. It built a government called the Palestinian Authority. It gave that Palestinian Authority billions in donations. And it’s based on hot air and nothing else.

And that thing finally collapsing now, over the last year, and the taking root of nonviolent movements, effective nonviolent movements, such as the fight of the Palestinian political prisoners with ongoing hunger strikes, such as the boycott movement and the antifascist movement inside of Israel, and the most important of which, the rising of national identity amongst Palestinians in the West Bank, Gaza, and inside Israel, and the linking of these three peoples irregardless of who are their leaderships, this [is] the most important element in the picture.

So the total disappointment with the peace process and the total–the collapse of hope that the conflict will ever end gave rise to a new kind of wave of understanding the conflict is never going to end. The generals and the capitalists that are sitting over there and are making money off the war don’t give a shit about us. Israel saw a huge social justice movement that we’ve covered here on The Real News for two years. That social justice came and fell, and nothing changed except there was a huge change in the public identity, in the public, the way people see Israel, and the way that the people see that their fight is not just with the Palestinians, it’s also with the government, and it’s also with each other. It has further segregated us inside Israel.

And so all these things together burst out. And if you look at–you know, people look at this war that happened this summer, this attack on Gaza, and they say, oh, it was really the worst attack on Gaza so far. They were right. But this attack was not just this summer. What happened this summer was, yes, 51 days of war, but it actually started not even with the teenagers getting kidnapped; it started with the Palestinian hunger strikers in the beginning of the year.

What we were seeing in January a year ago is that the African refugees were rising up, demanding freedom, because they were being shipped off to a massive prison in the south of the country, something very similar to a concentration camp for African refugees. So they were rising up demanding freedom. The Palestinian hunger strikers went on a hunger strike and were very close to getting achievements with that hunger strike. Hamas was on the verge of signing unity with Fatah, which would’ve been the last thing that would’ve saved it. And this was when we went to war.

So, since then, and if you were actually following what’s happening on the ground like we were on The Real News, that’s when the street-level violence started. And the war ended at the end of August, but the street-level violence never ended. In fact, it’s getting worse day to day to day. You know, a few weeks ago, a Palestinian bus driver, who drives an Israeli bus in an Israeli bus company called Egged, was beaten to death and hung in the bus that he was driving.

JAY: Because?

TARACHANSKY: Because he’s Palestinian. This is one of the things.

Now, there’s no doubt in any Palestinian’s mind that I’ve met that he was beaten to death and hung. But the police was claiming that he killed himself, and most Israelis believe that he killed himself. And this sparked a wave of bus drivers rising up against insecurity on the job, demanding that the bus company either separate them from the people who get on the–the passengers, or get a security guard, because the Palestinian bus drivers in the Israeli bus come company were saying that they were experiencing daily racist attacks, daily racist assaults. And the company refused. And forty of them have quit. So a third of the Palestinian workers who worked in the Israeli bus company quit because of racism and violence.

That’s where we are today. So six months of endless street-level violence.

JAY: Are there internal factors that you can see amongst Jewish Israelis that will change things? I mean, like, I interviewed quite a few families who lost people in 9/11 in New York, and I was told at least half the families either joined or supported the Not In My Name campaign. They didn’t want revenge. There were saying, don’t start another war, this is not going to bring my loved ones back. And they started getting their head around the context of why it happened. And there’s other examples in the world, including Palestinians, who have lost children, but they get the context. They don’t just want blind revenge.

But one gets the feeling that in Israel there’s been kind of a tipping point where the majority, even a preponderance of people are saying, they’re out to kill us, let’s kill them first, kind of end the conversation.

TARACHANSKY: Yeah. Yeah. The consensus in Israel has now–I mean, has gotten so bad that the general [incompr.] the consensus debate’s between expel the rest of them or kill the rest of them. So–.

JAY: It’s a real fascistization of public opinion.

TARACHANSKY: Well, we saw, during the war, protests where–I mean, you weren’t alive in the ’30s, but I’m sure you’ve seen a lot of archival footage of people holding up signs during the protest, reading “one nation, one army, one leader”.

JAY: It’s straight Hitler.

TARACHANSKY: I mean, that’s Mussolini, that’s Nazi Germany. I don’t know what you can compare that to.

JAY: So where are there factors for change within Jewish Israelis?

TARACHANSKY: Yeah. So I think that in America, in North America, there’s a lot of this mentality of there’s a problem, what’s the solution. We are light years away from resolving the conflict. I think a lot of people here in North America think that we’ve always been in conflict. But if you look at the history of Israel-Palestine, the history of this specific geographical spot, conflict over the centuries has actually been an exception. Peace and coexistence has been the rule. And our conflict is only about 70 years old, and we’ve already gone through huge changes as societies. And so let’s think a little bit before we start talking about solutions.

But what I can tell you is that profound changes are happening inside Israeli society, putting aside the Palestinian conflict for a second or the conflict for the Palestinians. Israel, as I’m sure you saw when you were there, is a very segregated society. You have the Russians here, you have the Ashkenazis there, you have the Mizrahim here, and then you have the Orthodox there, and Ethiopians here, and so on and so forth. And inside the Mizrahim you have the Persians, and then you have the Iraqis, and you have the Moroccans. And there’s very little mixing. Israel has almost zero social mobility. If you are born poor, you will die poor. You will not come out of the ghetto. And the media in Israel focuses on a couple of neighborhoods in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. And that’s it. What happens outside of these communities, what happens of Haifa, what happens in Palestinian majority towns, what happens in poor peripheral Mizrahi neighborhoods–completely absent.

That doesn’t mean that nothing’s happening. What is happening is that these segregated communities–and I think it’s a result of the social justice movement that was in 2011, 2012, when we saw the biggest protests in the country’s history, half a million people on the streets in Tel Aviv one night in a country of 7 million people. That’s a lot of people on the streets. As a result of that, people started looking around them, and for the first time identity politics is becoming something that is on the fore. So the Mizrahim are saying that–the Jews that came from Arab countries are saying, we’ve been oppressed all along for the Zionist Ashkenazi project. What about us? To the level of forcing the president of Israel, Reuven Rivlin, to apologize for Ashkenazi European condescendence towards the Mizrahim, something that would have been unimaginable. We’re seeing the Orthodox digging their heels further as new laws inspired by Yair Lapid’s party are forcing the Orthodox to go to the army, makes them more united and further in conflict with the [society].

So a lot of these groups, for various complex reasons that we don’t have time to discuss here, are getting more insular and more against each other. And so this is–I think this is a very important change. It’s because for so many years, with the illusion of the peace process, we were not looking at the real problems inside Israel.

JAY: Well, I was going to say, somebody once told me, I mean, I think when I was there for that film festival, that if it wasn’t for the external fight with the Palestinians, Israel would rip itself to shreds, especially the secular-Orthodox split.

TARACHANSKY: Yeah. Yeah. And this is what we’re seeing. Israel is now ripping itself apart. And fascism is celebrating in the ruins.

JAY: You’ve been on tour around North America with your film talking to a lot of North American Jews. What are you finding?

TARACHANSKY: Well, I was telling you about the New York screening. I’ve had about 30 screenings in 40 different cities, a massive tour along the West and the East coasts. And everywhere I went, I called up the organizers and I asked them to please contact the Jewish community in their town.

I made my film not for people that agree with me; I made my film for people that could–Zionists and unquestioning and questioning Zionists and North Americans and Israelis. I wanted people who would never see that kind of film to see that kind of film, because my film is not–you know, we’re talking here a lot about politics and a lot about geopolitics and things like that. That’s not what my film is about. My film is a personal story, and it’s a story of denial. And this is the film that I wanted to show in the Jewish community centers, in the synagogues, and in these places where we need to talk to one another. And everywhere, I call the organizers and I ask, please invite the local Jewish communities, please invite the local synagogues, invite them, get to them.

JAY: So did they come?

TARACHANSKY: They did not come. By and large, almost nowhere did they come. In fact, we couldn’t even get them to watch the film inside the organization, to say yes or no. We had to beg them in almost most of the places to just watch the film. They would say no.

And the most incredible thing happened in my New York University screening. The organizers took out a huge room for, like, 300 people, beautiful room overlooking the Empire State Building. And it was the same moment as the Eric Garner indictment, so a lot of people went to the protest. But the room was mostly full.

And as I’m running tech with the guy who’s responsible for the room ’cause the DVD wasn’t working, I see this group of, like, young 20-year-old students come in with a banner. And I immediately felt like they came to protest the screening. So I ran up to them and I said, I’m so happy you came. I see that you’ve come to protest. Is that true? And they’re like, yeah, yeah, we’ve come to protest your screening. I’m like, great. I’m so happy you came. Let’s go.

JAY: [incompr.] protest against your screening.

TARACHANSKY: Yeah. But they are the people I made my film for. I’m excited that they’re there, I’m so happy they’ve come, ’cause they will come, they will see the film, and then we can have this conversation, these very difficult conversations, essential conversations. And I told them, okay, where can I put you that will make you most visible? Do you want to stand on the stage? And they said, no, we’ll stand here on the side. We’ll just–it’ll be a silent–it’s not even a protest; it’s just a silent demonstration. I’m like, great. Let’s use–so I put them out. They pull out their banner. Their banner reads “856,000 Jewish refugees”, referring to the hundreds of thousands of Jews who were displaced from North Africa and the Middle East as a result of Israel’s creation. And I said, this is an incredibly important point. You’re onto something very important. And I’m really happy that you came, because the Mizrahi side to the whole Nakba conversation is a very important side. So I–.

JAY: Just quickly say what [Mizrahi is].

TARACHANSKY: Mizrahi is Jews who came from the Arab world and North Africa, the people that they have come to talk about. And this is something they were saying a lot. They said, we come here to show the other viewpoint. And I said, great, I’m looking forward to hearing that viewpoint in the Q&A after the film. And I apologized, ’cause I had to continue running, fixing the audiovisual.

And finally we fixed it. The film starts running. And I noticed that they fold up their banner and they go. So they all go to the elevator.

And so I run in the elevator, and the doors close, and it’s me with, like, maybe 20 of these activists in the elevator, stuck for ten floors, and I’m asking them, why are you leaving? You’ve come to protest the film. You have to see the film. And they said, no, no, we can’t stay for the film. And, oh, I have something to do. Oh, I also have something to do. I’m like, you can’t all have something to do. At least one of you, please stay for the film. They will not, they would not stay for the film. You know, when we come out of the elevator, we ended up standing in a lobby, and only one of them, one of the girls–most of them just ran outside. One of the girls stayed with me, and we ended up talking back and forth for about 20 minutes. And we could talk to each other. She was saying a lot of these things that you hear a lot. What about Hamas? What about Hamas? What about Hamas? We ended up talking a lot and breaking through. You know, she understood where I’m coming from; I understood where she’s coming from. And I told her, can you stay, can any of you please stay for my film? I want you–.

JAY: Well, you threatened their very identity.

TARACHANSKY: I didn’t threaten anything. I was begging them to stay for the film.

JAY: No, but they think if the film is persuasive in any way, it threatens who they are, and they have to start–think about who they are.

TARACHANSKY: My film asks questions. My film doesn’t tell you what to think. My film asks questions. And this is the point, this is why I’m telling you this story, is because two days later The Jerusalem Post published an article by the father of one of these activists, who was not at the event, describing what happened, having gotten none of the facts right. In his description, they came. They actually quote me saying something I never said, as if I said, oh, are you even allowed to protest? How would–I cover protest movements all day long. Why the hell would I say something like that? So they got all the facts wrong in the article. And then–and they made it seem like they came to protest, and all of us were just standing there staring at them aggressively and finally kicked them out, the complete opposite of what happened.

So not only did they get the facts wrong, but they also got this most important thing wrong is that they refused to watch the film. They don’t know what they’re protesting. They are looking at this conflict, like so much on the anti-Zionist left in America, as a soccer match where you have to take a side. You’re either on this side or this side, and you have to dig in, and you have to root for your team, and if you have a soccer match, you have a winner and a loser. And if we are the winners now, we have to maintain the victory, because if we ever lose, we will be on the losing side. This is madness. This is not what conflicts are about. These are not two sides. The Israelis and Palestinians are not two sides of a conflict between two nations.

And this is what was so disappointing to me about North America, because what these kids did by not staying to watch my film is that they’ve mirrored exactly what my film is about, knowing what questions you cannot ask of yourself, because you know that if you actually ask yourself these questions, everything will unravel. All the lies that you were told along the path, all the half-truths, all the propaganda, all the things that you told yourself have to be true because if they’re not true then nothing makes sense, all of that comes to an end and you have to look at Israel from a sober perspective. And this is what I’ve found here.

At the very least, in Israel they come. I’ve show the film to hundreds of people who are very much against the point of view of the film, and they had a very hard time watching it, but at least they come.

JAY: Okay. If people want to see the film, what do they do?

TARACHANSKY: Well, we’re just finishing the tour, so, unfortunately, they can’t. But they can buy a DVD, and we hopefully will have it on TV soon.

JAY: And where they can order the DVD?

TARACHANSKY: www.NaretivProductions.com.

JAY: Okay. Great. And for people in the Baltimore area, we’re going to be screening it sometime in, I guess, the spring.

So thanks very much for joining us.

TARACHANSKY: Thanks for having me, Paul.

JAY: So Lia, as she said, wants to engage people, certainly people [that] view her film or people that viewed this interview or, at any rate, anyone, but particularly North American Jewish people. So if you would like to engage with Lia, she will come back, and we will do a sort of live web thing where we do a live stream and you can engage her directly. So if you want to take up Lia’s challenge, please do, and we’ll let you know when. Just write us at contact at therealnews dot com and we’ll let you know when we’re going to do it.

Thank you for joining us on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

“Lia Tarachansky is an Israeli-Canadian journalist and filmmaker born in the Soviet Union. Her video journalism covered American politics, the Middle East, and Canadian-indigenous relations.”