Paul Jay and Freddie deBoer Discuss Independent Media, Censorship, and Hate Speech Laws

A discussion about independent media and ownership, censorship, self-censorship in media and a discussion about hate speech laws.

This interview was originally published by Plebity.

Jyotishman Mudiar

Hello and welcome. I am Jyotishman. I am the host of India and Global Left moderating this conversation between Freddy and Paul as part of Plebity’s Free Speech and Left Conference.

We are joined today by independent journalists Paul Jay and Freddy deBoer for a conversation on independent media censorship and hate speech laws.

Paul Jay is an independent journalist and documentary filmmaker. He is the founder, editor-in-chief, and host of theAnalysis.news, a site of political commentary and interviews. He is currently working on a documentary with Daniel Ellsberg titled How to Stop a Nuclear War, which is based on Ellsberg’s book The Doomsday Machine.

Freddy deBoer is an independent journalist based in Brooklyn, New York. He is the author of ‘The Cult of Smart How Our Broken Education System Perpetuates Social Injustice’ and his newest book is ‘How Elites Aid the Social Justice Movement’. Freddy is a self-styled old-school Marxist and writes regularly on his subtext about politics, Marxism, education, police reform, and other topics.

Welcome Freddy and Paul. I wanted to start with you, Freddy, on hate speech and hate speech laws. I read your article where you have argued that hate speech laws don’t work. So why don’t we start with your opening statement on that and then Paul respond to that?

Freddie deBoer

Sure. I mean, I think the first thing to say is always to point out that there is no such thing as a hate speech exemption to the First Amendment in the United States. One of my frustrations is that very often when liberals and leftists are talking about the concept of hate speech, they often talk as though there is such a thing as an already existing statute of hate speech, what it is legally in the United States. There is no such category as hate speech in the United States. You can say this is hate speech in a sense that you think is descriptively true, but there is no legal category of hate speech. And I also think that it’s almost entirely pointless to talk about the creation of one.

In order for there to be a hate speech provision for the United States, you would have to make an amendment to the Constitution to create that exception to the First Amendment. And among other things, an amendment to the Constitution requires three-quarters of the state legislatures of the United States to go along with something, which is just totally fanciful under current political conditions.

I think that Republicans would rightfully feel that any kind of a hate speech code written into the United States Constitution would be used primarily as a cudgel against them. I mean, I guess you can sort of theoretically define an idea of like a partisanly neutral, ideologically neutral hate speech code, but in practice, it would almost certainly be used more against conservatives than against liberals and the state legislatures of Republican countries, of Republican states, excuse me, we’re not going to get on board with that.

Hate speech laws don’t work because I think we have very good evidence that they don’t. The most obvious examples are countries like Germany and France. Germany and France both have aggressive anti-hate speech and anti-far-right extremism statutes on their books. They both ban explicit Nazism. Nazi parties are not allowed. Nazi iconography is banned in both of those countries. They both have a robust implementation of various laws in place to try to stop the spread of far-right parties, and they also have a huge far-right problem. Both of these countries that have really actively attempted to stamp down neo-Nazi propaganda and neo-Nazi parties have a significant neo-Nazi problem.

What you see in both cases, particularly in Germany, it happens over and over again, is that a party will rise, a far-right party will rise. It will have a lot of iconographies that are new but is in the vein that we’ve seen from fascist parties, and far-right parties in the past, and they will eventually be criminalized by the German government.

The Department of Interior, I think, is usually who’s responsible for those sorts of things. And then, once that happens, they formally disband. Maybe a few of their leaders will be arrested, but then they will simply scatter, and then they’ll reform and reconstitute new parties. You can ban the party. You can ban the particular expression of these ideas in individual parties and their specific slogans and the names of the parties. But the ideas that underlie them, right, are popular with a certain subset of the population. And so, they will continue to be expressed in some way in the political process.

In both Germany and France, we’ve seen the increasing salience of these parties in electoral politics. The sitting…

Jyotishman Mudiar

Okay. Sorry. So, can we just stay here and let Paul respond, and then we can come back to you?

Freddie deBoer

Sure.

Paul Jay

Well, this is not my preoccupation, but I don’t believe in some absolutist free speech. And there are certain forms of hate speech laws, which I think can work. I’m living in Canada right now. We have a hate speech law here. And as far as I understand it, the experience with it has not been so bad. It’s essentially aimed at overt forms of racism and fascism. I mean, overt. And I personally have no problem with that. Now, whether you could have a law like that in the United States constitutionally is a whole other matter.

But if we’re talking about, is this something I would be for, I am for it. And I am not for, for example, which I do understand might be the case in Germany, that there should be a law against any interpretation of history. I don’t think ipso facto, by saying there wasn’t a Holocaust, that’s automatically hate speech. Although maybe it is, I don’t think any court should be involved at this time in deciding how history is discussed. But hate speech, whose real intent is to mobilize people against a specific race, group, or ethnicity, I have no problem banning that.

As I say, I think the Canadian experience on that is not so bad. But either now or a little later in the conversation, I think we really have to broaden this conversation. This isn’t about a particular hate speech or censoring hate speech without looking at the context.

I’ll get into it more later, But there is a war going on throughout this world. And the one thing that’s really banned from mainstream media, is to discuss the nature of this war. And you can’t even talk about this without getting kicked off and never invited back. You can’t say the most obvious thing, which is we live in a class society. And throughout the world, there is a class war going on every single day.

Now, sometimes this breaks out into state-to-state war, the aggressive invasion by Russia and Ukraine, the Americans backing the Saudi war in Yemen, you can go on. But I lived in Baltimore for eight years, nine years. There is a class war against black workers every single day. And even the Department of Justice, under the Obama administration, investigated the Baltimore police force and concluded that every single day in Baltimore, people’s constitutional rights are being violated. Why? So that there can be a cheap labor force available for institutions and corporations in Baltimore.

In the context of this kind of war, let’s then talk about censorship, and hate speech. But on the face of it, in a very narrow interpretation, meaning very overt racism, very overt fascism that could lead to mobilizing people, sure, I don’t have a problem with that. Let’s, there’s a reason why so much money is invested in propaganda. It’s because it works.

Jyotishman Mudiar

Freddie, would you like to respond to Paul’s point that it does work? And he makes the point that in Canada, it seems to be working at this point.

Freddie deBoer

Sure. I mean, I think that Canada is distinct from the United States in all manner of ways, for, you know, a variety of historical and cultural reasons. I just don’t believe that, of course, we’re in a class war. I think the first thing I would say in response to that is one of the things that really disappoints me about the contemporary left is that the definition of who the biggest enemy is has changed within my lifetime. I understand the real enemy, the person who does the most damage, is a guy who puts on a $2,000 suit and goes up to a tall building on Wall Street, and as an investment banker, ruins the lives of ordinary Americans every day. But in my own lifetime, as someone who’s been an activist in left circles for his entire adult life, the focus has fallen farther and farther from that person; that immensely wealthy tycoon on Wall Street. It is now more and more a Proud Boy or some other, you know, part of the lumping fascist movement in the United States who shows up at a protest and throws some rocks and punches some people who have no actual power to affect anything in the world.

I mean, to me, the way to win the class war is to understand that the people who are the greatest danger to the working class, to the environment, to people of color, to LGBTQ people, et cetera, ultimately are the people who hold respectable positions of power within the established economy. It’s not the fringy John Birch society types. I think those people are despicable but I don’t think that they actually control the sort of bulk of the disruptive power in the United States.

I would also say like, look, look at an issue like acceptance of interracial marriage. Nowadays in polling, even Republicans poll north of 90% of people approve of interracial marriage. But as recently as the early 1990s, a majority of Republicans were consistently saying that interracial marriage was immoral. How did we achieve victory in moving that needle over time? We didn’t ban the idea that interracial marriage is wrong. We didn’t carve out an exception in the Constitution and say, you can’t argue this. Rather the force of the idea, the fact that we were morally correct, right? The fact that people lived lives demonstrated that these marriages were not destructive. The fact that we demonstrated our values in a lived sense, created a natural organic rejection of the idea that interracial marriage is bad.

I think that that’s just always going to be in the long term, a more permanent and durable way to achieve change than by trying to ban things.

Paul Jay

Yeah. Well, I don’t think I disagree with a word of that. Any attempt that goes beyond what I was saying to ban overt racist and fascist language that is meant to incite people to attack in a racist and fascist way. Anything else, I’m not for, anything. And of course, you have to win by persuasion.

In fact, why is there such a Trumpist movement? Why did 75 million people vote for Donald Trump? It’s not because the majority of them are racist and fascist. The majority of them are not by any means. The majority of them are just fed up.

I interviewed a guy in the lead-up to the first Trump election where he won in a diner outside Baltimore. We asked him how he felt about Trump. And he said, “Well, he’s a liar. He’s a scumbag. I don’t trust him. I’m going to vote for him. What’s that tell you about what I think about the other guys?” The whole system is toxic. And it’s toxic for what you just said. It is how stuff is owned. It’s the concentration of ownership.

The concentration of ownership, particularly in the financial sector, which has become so parasitic that far more money is in this casino capitalism than investing in anything productive. People are suffering from that. And the corporate Democrats and the liberal face of this system have simply written off those 75 million people that voted for Trump. They don’t give a damn. And they till the soil for such crazy shit to be believed. So if you want to deal with the crazy shit, no, you don’t ban the crazy ideas. You don’t ban people that believe in this theory or crazy theory. What you do is invest in a public education system right across the country. And you actually pay teachers properly. And you train teachers to actually know history.

Look at some of the papers kids are writing in school about the Second World War. They absolutely haven’t got a clue who were the Nazis, who were the Soviets, who were the Americans. And they’re getting A’s. Why? Because the teachers don’t know any better than the kids do. If you really want to deal with the descent of so much of the population into a kind of, I don’t know what else to call it, a kind of ignorance that makes people susceptible to being recruited into a theocratic fascist movement, it’s the complete collapse of a decent public education system outside of major cities.

Freddie deBoer

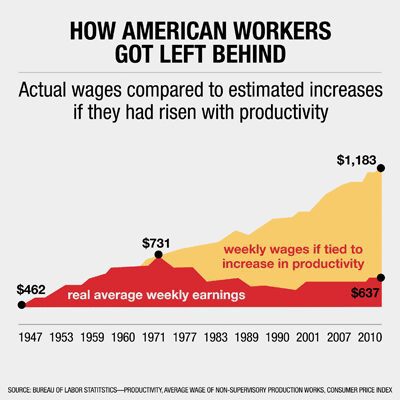

Yeah, I think casino capitalism, I think, is just the right term. I think that one of the things that I think that we could all do a better job of sort of explaining to everyday people is the degree to which financialization is not just found in the financial industry anymore.

One of the things that emerged from the financial crisis in 2008-2009, a lot of people didn’t know but became apparent. For example, General Motors was making most of its money, the majority of its profit were not coming from selling cars. It had created a financial bank that was attached to it and was making bets on the economy. And the same thing was true of the major airlines, the same thing was true of General Electric.

One of the things that happen when you have this financial sector that is promising people such incredible returns, you say, well, look, you can go and you can build a factory and you might make 5% a year, or you can invest with me and you can make 20% a year. When you have that kind of a margin because you’re making these extremely risky bets like they were making with mortgages and mortgage-backed securities and derivatives and all that stuff; ordinary investment can’t compete.

If I just have an old-school factory in which I’m building widgets and I can employ people and I can send these things out, then that looks like a much less attractive investment opportunity to investors.

One of the things that happen is that financialization spreads further and further across the country because in order to compete with the interest rates that some of these banks are dangling in front of people, institutions that are not fundamentally financial have to use those shenanigans too, which of course is fine until inevitably whatever cracks are in that financial model happen to break and we have explosions as we had in 2008 and 2009.

Jyotishman Mudiar

Yeah, I just wanted to quickly add that the implication goes beyond the country and particularly its impact, the impact of finance capital on the global South has been very, very extreme.

As we speak, we are seeing country after country, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, facing the balance of payment crisis. And one of the roots of this was this liquidity was following the global financial crisis in the global North that went into these bond markets, through the bond markets into these countries of the global South. And the moment interest rates are high in the global North, capitals are switched back, leaving the country’s money into depreciation, trades falls, balance of payment goes into a sort of complete toss and then IMF goes in and imposes the austerity and eventually the burden is transferred into the working people.

Sorry for just this addition since I come from the global South, I thought there was this great moment. I want to quickly switch from this discussion, but if we can just quickly put this thing away since Paul mentioned school education and I’m taking university as part of this and maybe my question is particularly relevant to university. What are your thoughts about the rise or this conflict around free speech in university, particularly with regards to what we generally understand as cancel culture or issues of diversity, equity and inclusion? Do you see a particular threat in that or is it blown out of proportion by the right wing as a sort of weaponization?

Paul Jay

Well, I think the answer is both. I think it does get blown out of proportion by the far right and I also think it gets exaggerated by sections of the left. We are facing an existential threat. The climate crisis and the risk of nuclear war have never been more threatening, so you cannot judge an issue without starting there.

So if a particular professor or a particular thing is being said, it doesn’t mean, it doesn’t offend someone’s identity, it doesn’t restrict some rights. I’m not saying people should lay down in the face of it, but is it the primary issue? And if we need to build a unity of the people to force real policy, real action on climate and real policy to reduce the risk of nuclear war, then everything else has to be judged in the context of that.

You got to pick your battles and it serves the interests of the oligarchy, to use Bernie’s words or whatever, to keep people fighting over these other issues.

Right now the abortion issue is after years of hurting the Democrats because it pushed so many votes towards the Republicans. Now all of a sudden it’s galvanizing some vote that might help the Democrats and it’s clearly a legitimate fight for women to control their reproductive rights, but there are a lot of serious people, honest people, ordinary people who are religious and in good faith, not in bad faith, think abortion is against their principles. I don’t think women should have to give up their rights because of that.

On the other hand, there should be an enormous effort, including knocking on doors in all the areas where people vote for Trump to say, look, okay, we’re going to disagree on this, but we’re faced with an existential crisis. Human civilization could end. So how about we agree at least to reduce the risk of nuclear war? If you don’t get the climate science, let me tell you what I know about it. And, you know, we all know there’s lots of us aren’t going to agree on some of these other issues like abortion or even, you know, gay marriage. Okay. We won’t agree. But in the context of what we’re facing, the threat we’re facing, you know, if there was like a meteor about to hit the earth, you want to be arguing about abortion? Well, that’s the kind of moment we’re in.

And the problem is the corporate Democrats, which essentially are the political face or much of the financial sector, they don’t want effective policy to deal with climate. Because what is effective policy? It’s a kind of central planning. You actually have to plan a green economy. And it can’t be done by anywhere other than government. It’s clear the market can’t do it. And as much as even they know, like you listen to Larry Fink, who runs BlackRock, he’s fully aware of the facts of how dangerous the climate crisis is. But they don’t want a kind of government planning.

Now, it’s not they’re against central planning. They don’t mind when the Fed bails out banks. What is that but central planning? The bloody Pentagon is central planning. There’s lots of central planning, but essential planning done by a government and politicians very beholden to the financial sector. But they don’t want to open the door to a transformation to a green economy that will require pulling back on some of the profit centers they have in fossil fuel companies and such, even though they know human civilization is threatened by it.

Freddie deBoer

Yeah, I would also say that my response is like, it’s both at the same time. Look, I’ve written a lot about civil liberties on campus. I do fundamentally think that conservative students and conservative professors should have the right to hold and express the opinions that they do. I also think that it’s very fraught for the American university system if it really does become entirely one side of the political spectrum because that means that it’s much less defensible.

I mean, one of the things, there’s been this terrible defunding of America public education, higher education in the last 20 or so years. And one of the things that Republican state legislatures always do is they say, one of the reasons we’re cutting funding is because these are just leftist indoctrination camps anyway, et cetera, et cetera. I do think that there’s, of course, in a certain sense, these are tempests in a teapot, but I think it’s worth asking, why have young people today become so habituated to expressing their problems in a way that is very sort of parochial, so very like my campus is the world and I need to clean up my world and I appeal to the dean and he’s the highest authority there is, and my problems are all about offense and my desires are to limit people’s language.

I think you have to look at that and say that these are young people who have grown up with a sense of disenfranchisement. That, in other words, part of the reason why so many young people spend so much time with the language policing and with freaking out about who gets cast in what movie and having social media freak-outs is because they’ve grown up into a political system in which they don’t believe they have representation. In other words, they look at the political system in which they’re embedded and they don’t see themselves as having a voice, as having an opportunity to really influence things.

One of the things that I’ve found myself is there’s a really interesting combination and kind of dark combination among a lot of young people of great idealism but also nihilism, in the sense that they have very developed political instincts and they have a strong sense of right and wrong, but they don’t believe that they can actually create change. They don’t think that anything’s going to get better, and so I think that part of the reason why you see these perpetual blow-ups on college campuses is because it’s one of the only places where people of that age feel that they have any power. They don’t think that they can get a political system that actually represents their interests. They don’t think the economic deal is going to get better for them. They’re looking at a world where healthcare, education, and housing just keep getting more and more prohibitively expensive. Most of these kids don’t believe they’ll ever be able to own their own home and they’re probably right, and so they see this very pessimistic outlook on the world and they say, well, look, here at the place where I spend $30,000 a year in tuition checks and where we can raise our voice and yell at administrators who can give us what we want, here we’re going to exercise our power. It’s the expression of this is the only place I feel enfranchised, the only place I feel empowered, so I’m going to become more and more controlling of that space.

Paul Jay

Well, I’m not sure that’s so bad. Where else are they going to fight except in the school where they spend most of their time? What I’m more concerned about is the way universities suppress discussion indirectly by who they hire. For example, the Israel-Palestine question. I mean, how many professors have either lost their jobs or are scared about their jobs if they talk about what’s really going on in terms of the apartheid state in Israel against the Palestinians? The institutional power is far stronger than anything the left is capable of doing. That said, I think it’s important, don’t divide the students on secondary issues. I don’t mind closing down a member of the Nazi party if they’ve been invited to speak. Go there, scream at them, disrupt. It’s fine with me. I think suppression of overt Nazism, again, there’s a difference between conservative opinion, right-wing positions, and overt Nazism. But the main thing the left should do is promote as much open discussion and debate.

If you believe facts are on your side, you don’t fear discussion and debate. And I wish, I hope the left one gets over so much sectarianism. How much left just winds up spending its time attacking other portions of the left? And don’t divide the student body over secondary questions. There’s some polling recently, even amongst Republicans that consider themselves seriously conservative Republicans, it was something close to 20% of them thought climate is a legitimate threat, the climate crisis. 10% of those Republicans thought it was at the amongst their top three concerns, the climate crisis. So how about trying to win those people over and talk about climate and try to subdue the fights on some of the questions you know you’re going to disagree upon. Again, the meteor is about to hit the earth. You know that movie Don’t Look Up. Well, we’re in that kind of moment. We better be smart and tactical to try to build as much unity. I’m not naive.

There’s a section of the population that because of indoctrination, however, the belief system, there’s a lot of money being invested in getting people to believe that Trump is a vehicle of God. And the Christian theocracy, I think is a serious, it’s not the Proud Boys that are a problem. It’s amongst the elites that are using their money to mobilize Christian nationalism amongst the people. It’s a very serious threat.

Mikey Weinstein from the Military Religious Freedom Foundation, who do a lot of work on pushing back against Christian theocracy in the military, they think as much as 30% of the military have been recruited now actively into Christian theocratic forms. The real story of January 6 on Capitol Hill was not what happened on January 6. It was the lead up to January 6 where 10 former secretaries of defense, the former Supreme Commander of NATO and an editorial in the Financial Times, all on January 4th, essentially said a coup was in progress. And this is, by the way, another form of censorship because you can’t say this at all in mainstream TV. They don’t want to acknowledge there was a coup in progress on January 4th. They want to just focus on Proud Boys on January 6th, which is the more irrelevant part of what happened.

But as I said earlier, propaganda works. And there’s a lot of money invested in mainstream media, online media, social media, to recruit and persuade people. But how do we deal with it? Even if you advocated banning it, it’s nonsense. You have no power to do so. We need to talk to people and persuade people. And so as far as free speech on campus goes, if facts are on our side, are meaning the left, and I think they are, let’s rely on them.

Jyotishman Mudiar

Freddie, do you want to respond very briefly before I shift the conversation?

Freddie deBoer

No, I mean, I think that’s all said. I think that there, again, as sort of little sympathy as I have for these Republican voters that we’re talking about, again, I think that what they share with these very liberal college students, again, is a sense of disenfranchisement, which is part of, which is, I mean, in one sense is crazy, right? Because no one is more overrepresented in our political system than the average white male Republican. But at the same time, if you look at things like QAnon or the rest of these wild conspiracy theories, I think part of what unites all of them is a sense that the system is broken down, change is impossible within the system. And so QAnon is like this apocalyptic sort of conspiracy, right? Q will come back and there will be a great cleansing and there will be fire and blood in the streets, et cetera. And that sort of stuff often comes from a sense of among ordinary people that the system is rigged, which it is, and that change isn’t really possible. And so that prompts people into these extremes within their own little affinity groups, because you won’t think that you can work within the system to create change. You’re always going to sort of gravitate towards just getting more and more intense within your own little niche.

Paul Jay

And the other thing I would add to that or suggest to people on campuses and such. Daniel Ellsberg was a militant who released the Pentagon Papers. I’m doing a film with him now on his book, Doomsday Machine. He was a nuclear war planner. I interviewed Larry Wilkerson a lot, who used to be Colin Powell’s chief of staff. They were militant, militant cold warriors. They really believed the Soviet Union could try to have a first strike against the United States. They thought it was trying to take over the world. They believed all that stuff. And then they came to realize it was bullshit.

So even people that believe in the QAnon stuff, and I agree what was just said, it’s out of desperation. You pick up, you believe in this stuff. Your own life doesn’t really validate it. So if you’re going to talk to people, listen, some people are nuts. They’ve been driven mad by a culture that’s essentially irrational, and maybe you can’t talk. But most people who voted for Trump are not completely nuts and are not QAnon. And even if they are, just set that stuff aside. Just say, listen, do you think there’s a climate threat? Do you think climate crisis is real? So argue on that. Forget the rest of the stuff. Most of the ordinary people don’t have an economic interest in these crazy shit. But there’s a gang of billionaires who do have an economic interest in people believing this stuff. So what Fred said earlier, yeah, let’s get the attention back on these guys in the $2,000 suits, including the ones that are working around Trump, that are behind Trump. And let’s try to have as much unity amongst people as we can.

Jyotishman Mudiar

A lot of stuff about beliefs is due to alienation. If you read military or war histories, you very quickly realize how easily people understand the ravages of war, just by being involved, which they generally may not have understood. And thinking about this alienation, this is a good segue into my next discussion, which is the internet. This is the sort of our great moment of transformation, the new market, sort of the way Carl Polanyi would say the great transformation of the 28th century. This is our great moment, perhaps in the last 20 years. So I want to start with you, Paul, about the issue of censorship in the digital market. And there are issues about arbitrary usage of algorithm. There are issues about involvement of government. And there are issues about corporations in the digital market using our data to manipulate us, or even turn ourselves into commodities.

So can you, if you can just tell your story very briefly, but also respond to this sort of the moment we are living in, and the issue of censorship that comes with the internet space?

Paul Jay

I’ll try to do it quickly. Yeah, I run a website called theAnalysis.news. And I did this story about January 6 on YouTube, we have a YouTube channel, where I pointed out that the real issue was the events that led up to January 6, not January 6. Again, about all the various mainstream sources that were talking about an attempted coup. Essentially, Christian nationalism within the military.

And in the video, I also pointed out that the corporate America had decided they’d had enough of Trump and wanted a peaceful transition. One, they don’t so fear a Biden presidency. They know in the final analysis, there may be some legislation they don’t like, but it’s not going to challenge their essential power.

But something I pointed out in the video that was reported in mainstream media and then disappeared, the doors of Capitol Hill were breached at 2.10 in the afternoon. At 3.10 in the afternoon, the Association of American Manufacturers called for Vice President Pence to invoke the 25th Amendment and remove Trump. That means the preponderance of the elites had decided that this guy had gone nuts and they couldn’t trust him, and they feared this kind of coup.

Well, that video, because it targeted Christian nationalism, because it exposed how corporate America’s role in this, and I should say the Association of American Manufacturers loved Trump right up until those days. They got everything they wanted in terms of deregulation and tax cuts. YouTube took that video down and gave me a warning, official warning.

Jyotishman Mudiar

And it was selectively you, not the big media.

Paul Jay

Yeah. Well, what happened is they said, because we had a clip of Trump speaking to the crowd just before they went to Capitol Hill, we were promoting the idea that the election was stolen and promoting disinformation. Now, it was obvious in the video we were denouncing Trump and not just…

Jyotishman Mudiar

Just to be clear, the big media could run the same video.

Paul Jay

They all did. That same clip had been on every single mainstream media on YouTube. So then, as an experiment, I took out the Trump clip and I added more, because I knew more about the story of the role of Christian nationalism in the lead up to January 6th, and I published that story. I also raised the issue in the first and second story. What was Mitch McConnell’s role in this? Because nobody wants to talk about that.

The three guys that oversee the Capitol Hill Police are the Sergeant of Arms of the Senate, the Sergeant of Arms of the House, and for some reason, the congressional architect. But the guy who really runs as senior is the Sergeant of Arms of the Senate. Who does he report to? The majority leader, Mitch McConnell. And the chief of police of the Capitol Hill Police was actually quoted as saying on the morning of the 6th, he went to the Sergeant of Arms of the Senate and asked for the National Guard to be called in then. And according to the chief of police, the Sergeant of Arms said to him, well, I have to go ask my boss, Mitch McConnell. And I never heard from him again, says the chief of police.

Well, in my report, Christian nationalism, focusing on Mitch McConnell’s role and the lead up. So because I took out the Trump piece, they didn’t take the piece down. Then I tried to buy an ad to promote the piece. I got a letter from YouTube and then from Google saying, this piece spreads disinformation. You are now banned from advertising on all Google platforms forever. You, Paul Jay, me personally. So then I interview Mikey Weinstein. I do a piece about Christian nationalism. I don’t even talk about Trump’s role. It’s just about Christian nationalism in the military and the role in the lead up to the 6th. They take that piece down. I get a second strike now. I’m one strike away from the channel being closed down.

The only reason I didn’t get closed down, I know Matt Taibbi and Matt wrote a piece about this and contacted YouTube and they knew he was going to have a piece exposing all this. And so they actually did an apology. They said they made a mistake and they took away my lifetime ban and put up a couple of back the stories, but it hadn’t been for Matt. They would have closed the channel down.

So we cannot leave deciding what’s legitimate information and misinformation up to big tech. They cannot have the right. I mean, these things should be publicly owned anyway. If there’s going to be something like a YouTube, it should be publicly owned. There’s just no way a private corporation. And then even if it’s publicly owned, there has to be a process within which there needs to be real democratic public participation into what information is there. And even there, it shouldn’t be about banning stuff. It should be about properly financing independent news and investigative journalism so you can actually persuade people.

And just to add one thing, I do think this Dominion voting machine lawsuit against Fox, maybe that’s a good model. Maybe we need to create a fund for class action suits against broadcasters that publish bullshit and let it be fought out in a courtroom with evidence where you can actually prove they’re knowingly publishing lies. Because how much of this war after war is based on mainstream media promoting outright propagandistic lies to support the war? Maybe we should have an ability to have class action lawsuits against this. I mean, obviously the real solution is real democratization, real public ownership of the media, diversified media, which means we have to find ways to gain more political power. It’s not just coming up with some ideal scheme in our heads.

Jyotishman Mudiar

Freddie, go ahead.

Freddie deBoer

Yeah, I think we’re in a very weird time in terms of the balance of power between independent media and corporate media in a certain obvious sense. It’s never been easier to spread your message as an independent purveyor of the news or opinion. The technological tools have never been more accessible or more widespread.

My father was, he was an avid fan of the Village Voice, but also of these little all weeklies, printed newspapers from different cities across the country. When we were growing up, when I was growing up in Connecticut in the 1980s and 1990s, in order to get his hands on a bunch of these all weeklies, he had to just have friends in those cities, just send them in the mail every week or every month or whatever it was. In other words, there was just no distribution system. For the Village Voice, you could get it delivered, but for most of these little papers, if you wanted to get one and you didn’t live in that town, you had to have someone send one to you. Some of them had subscriptions, some of them didn’t.

Now, obviously, everything’s online. It’s incredibly cheap and easy to set something up. When I first started using the internet seriously, you had to pay money for photo hosting. You had to put down real money just to put some photos online, and now you can get unlimited whatever.

At the same time, we have this series of very real and major challenges to establishment or mainstream media. There’s not a single show on CNN that still gets more than a million viewers regularly. There’s been a terrible collapse in the number of local newspapers across the United States in the last 10 years. The total number of people employed in newspapers was cut in half between 2008 and 2018. You’d think that the balance of power has shifted decidedly into independent media. In some ways, it has, but in a certain sense, it’s bad for everyone, I think.

A fundamental problem we face is that actual news, news gathering process, has never been a big moneymaker. When the New York Times sends a small team of journalists to Syria, and they’re there for three months, and they have to pay for their plane tickets, they have to play for their food and their lodging, they have to pay for security, they have to pay for translation, they have to pay money to grease the wheels with the local authorities, etc., that all costs a lot of money. The number of people who read the stories from Syria that come out of that is quite low compared to other things. Hard news, unless it’s about very topical stuff, hard news just doesn’t do big numbers.

What’s always kept the news making industry afloat is bundling. Your newspaper had the hard news up front, but it also had the personals, so the classifieds, the demise of which was a horrible financial blow for local newspapers, the classified ads, which you don’t need anymore because you have the internet. They had the opinion section, which is much cheaper to produce than news. Again, a news story could require you to send reporters into the field for months at high expense, whereas an opinion takes one person just thinking and writing for a few days. You had the recipes, you had the comics, Garfield, etc., you had the crossword.

One of the things that the internet has done is that it has broken the bundle up, where if you want a crossword, there’s just an unlimited number of free crosswords that you can do online. You will never run out of crosswords to do for free online. If you want comics or cartoons, there’s an unlimited number of free cartoons you can read online. If you want opinion, like the kind that I produce, you can look up a million newsletters and websites and blogs and whatever and get all that opinion.

The problem is then how does the news get subsidized? I think that this is a really deep question and a really powerful one because that old model, I am thankful for my success at creating a newsletter, but I don’t have the skills or the funding or the wherewithal to go and investigate what’s the story with the drug war in Mexico right now in the cartels, etc. You have that problem there. Then you have the problem that Paul just talked about, which is that while we have the accessibility of all of these tools, they’re ruled from the top down by a financial elite who can do whatever they want because they’re privately held tools.

We’ve seen with Twitter, recently Elon Musk was upset with the company’s substack and so he throttled the reach of substack newsletters on Twitter. He owns the company so he can do whatever he wants. YouTube can arbitrarily decide who can run a clip of Trump and who can’t. Ultimately, they’re not a public agency. They’re a private company so they can do whatever they want. That’s the other half of this, which is that yes, we have all these incredible digital tools for distribution, but at the end of all of these digital tools always, there is some corporate bureaucrat who has the ability to pull the plug, dictate standards, twist the algorithm, do whatever they want.

In a certain sense, it’s never been easier to reach an audience, but the state of actual news gathering is very, very fraught and your ability to disseminate your message to your audience is always at the whim of a corporation.

Paul Jay

Let me just add a couple of things.

Jyotishman Mudiar

I’d also like you to call to say at least two sentences about how do you look at real news, having founded you and some kind of that kind of experiment. How easy or difficult it is to do that?

Paul Jay

Well, real news, I’m now at the analysis.news. I’m not working at real news anymore for acouple of years. Well, it goes to what I was about to say, which is in spite of, what’s that joke about everybody has the right to walk in the front door of the Ritz hotel? Not everybody can afford the room. Yeah, we can all get to YouTube, but who’s actually dominating YouTube is all the mainstream media companies. What’s one of the most visited sites in the world? CNNs and New York Times is one of the main sources of online news. Anybody can start a YouTube channel, but can you actually break through to a large audience? That’s where YouTube’s algorithms can really get to choose the winners and the losers.

When Julian Assange was arrested, in his handcuffed hands, he was holding my book. It was a book based on interviews I did with Gore Vidal called The History of the National Security State. The next day, Dan Ellsberg said to my wife, he said, you be careful, you’re really on their radar now.

The same thing happened. I was in Baltimore during the Freddie Gray uprising, and we did a lot of coverage, giving a real class interpretation. In fact, our building was the headquarters for a lot of the organizing that was going on amongst the protesters. I was really on the radar then too because the local fusion center where the NSA and the FBI and the state police and probably the CIA all work out of this fusion center with the local police department. Well, they were all infiltrating, watching our building.

Then this reporting I did on January 6th, clearly an algorithm kicked in that said, okay, this guy has already been flagged. If you look at our numbers on YouTube, they greatly drop after they start taking down our stories. Matt Taibbi has been doing these stories on Twitter, some of which has shown how the FBI algorithms talk to the Twitter algorithms. That’s got to be the same case on YouTube.

Here’s a practical suggestion. The progressives that are on the hill or even at state levels, if they can do it, have a hearing where you force YouTube to reveal the algorithms and whether or not they’re talking to the FBI and try to actually out the way the state agencies are creating agendas for social media. That would be a useful service because there’s simply no question is happening.

Anyway, just back to your point about the Real News. I’m sure there were things we could have done better and same thing what I’m doing now with the analysis.news, but it’s very hard to break through to a mass audience, almost impossible unless you’ve got enormous amounts of money to promote and buy advertising. Even then, like in terms of mainstream TV media, it doesn’t even matter how much clout you might have. Often, they’re not going to let you on anyway.

I think I’m an interesting talker. Maybe other people don’t, but a lot of people seem to. I never get invited on anything. Nothing. Occasionally, I used to get invited on RT and then I said to RT, I said, fine, but I’m not going on RT without critiquing Russia, which I did. I never got invited back on RT again. Same thing. If you talk in real terms about what’s going on in the world, you don’t get on mainstream TV. I’ll give you an example of something which is nuts.

I interviewed Senator Bob Graham, who was the chair of the Senate Intelligence Committee, co-chair of the joint congressional investigation into 9-11. He told me on camera that Bush and Cheney deliberately disorganized the Americanintelligence agencies, and two, didn’t just do that. They actually actively facilitated the 9-11 attacks in a few ways, including that famous memo, bin Laden plans to attack America.

Graham told me that the normal protocol after a presidential briefing is called a principles briefing that goes out in the next day or two. Heads of agencies, secretaries of departments, undersecretaries. If there’s anything in the presidential briefing that requires action for national security reasons, it’s in the next principles briefing. Well, Graham tells me in the next principles briefing that memo bin Laden plans to attack America was omitted. Graham says this was part of actively facilitating.

I emailed every major news organization in the country. It makes no difference whether Graham’s right or wrong. It’s just he’s a serious guy. The fact he said this is news. I will give you this video clip for free. All you got to do is credit me with doing the interview. Not one news source, not a single one, including people I actually knew personally, not a single one followed up and asked me.

There’s certain lines you must stay within to break through, whether it’s mainstream media or on social media. It makes no difference whether you’re fact-based. You could go outside the lines of the official narrative. It’s very hard.

What is the solution? The solution is, we have to really find ways that alternative media cooperates more, creates something bigger with more clout. Bernie Sanders’ campaign shows you can raise a ton of money online. It isn’t a hopeless situation, but we have to find ways to create some clout and do get people elected. Then once they are elected, they got to use that to expose these kinds of issues.

Imagine having a guy, like I phoned a guy, I’ll end quickly. He ran World Affairs for one of the coverage for one of the major newspaper chains. I knew him. I said, Bob Graham, serious guy, right? Oh, yeah. Intelligence insider. Oh, yeah. Head of the Senate Intelligence Committee. Here’s what he just told me. I told him and he says, holy shit. I said, I got it on video. You can have it. Christ. I knew this guy.

I’ve got a mainstream news network background. My documentaries have been on all the major networks, A&E’s and BBC’s and you name it. My television show was a debate show for 10 years on CBC. I was the exec producer. I’m not coming from nowhere. I’ve got some mainstream credibility. Zero. They wouldn’t touch the story. Even there’s so much credibility to it.

We have to build something with our own resources. If there’s plenty of money amongst us to do this, if we can break out of this, all of us competing with each other.

Jyotishman Mudiar

Freddie, I give you the final words. If you can also tell a little bit about your experience with the subscription driven sort of media, how independent you can be and do you feel like making a broader impact at all, if anything?

Freddie deBoer

Well, it’s interesting. I am frequently brought to things like this. I’m often sort of invited to be a voice of sort of independent media. On the other hand, my last book came out from McMillan. My new book is coming out from Slamid & Schuster and I’ve been in the New York Times and the LA Times and the Washington Post and the Guardian and Harper’s, et cetera, et cetera.

Yeah, look, I’m very lucky to be successful making the newsletter that I do. A really good post will get like 120,000 views typically. I’ve had a couple of posts that have been sort of just by luck have sort of gotten to like 200 or 250,000. I’ve been blogging for 15 years and I have long since given up on understanding the gods of what gets read and what doesn’t. I mean, I cannot tell you how many times I have labored over a piece for days and days, spent hours and hours on it, researched deeply, cared very much about it, thought that it was a piece that had a real chance to do something and it just goes nowhere. And then will dash something off in an afternoon that doesn’t mean that much to me and it will be one of my biggest pieces.

Certainly, there is a trade-off to be had between sort of the freedom of doing my own thing and the broader audiences of the other sort of doing mainstream stuff. I frequently have to sort of let young writers down and let them know how poorly mainstream places pay.

I mean, what I very often will hear from young writers is some version of, well, I’m sweating it out now, not making a lot of money blogging or working for sort of low prestige sites, but someday I’ll make it to the New York Times or I’ll make it to New York magazine or I’ll make it to Harper’s and then I’ll make real money. And I have to tell them places don’t really pay as well as you think they do. Like it’s really-

Jyotishman Mudiar

How much does the New York Times pay for a column?

Freddie deBoer

So the online only column that I put out in 2022, I think, I put out a piece about the American socialist movement for the New York Times. It was 1800 words, 2000 words. I got $750 for it. Print stuff, when I was in the print magazine, I got $4,000 for 3000 words. But that was a long, long process with a lot of sort of things like that, which is certainly not bad money, but if you’re going to do it as a freelancer, you’ve got to be churning it out all the time.

So one of the things for me right now is if I am thinking about doing, okay, I want to get a bigger audience, I’m going to write for a mainstream publication. I have to sort of do the math in my head, even if I am committed to doing that, where on a per word basis, writing for my newsletter makes me much, much more money. It makes me much more money than writing for the New York Times or for whoever.

But at the same time, my newsletter audience is largely a self-contained one. I have about 40,000 people on my mailing list. The average post gets about 40,000 or 50,000 views. Like I said, occasionally they go to 100,000 and maybe three or four in the history, in the three-year history or whatever of my newsletter, they’ve gone to 200,000, 250,000. But it’s usually the same people. So it’s sort of like a hermetic environment where I’m getting paid well to be a writer, which is the only thing I ever wanted, but I’m not really influencing the broader conversation. And then every once in a while, a post will go big. But like I said, I’ve given up on figuring out why.

Yeah. And the thing is my ability to publish in various places, mainstream places, has very little to do with the quality of my recent work. It has everything to do with who is cool with who. What person who likes me recently became an editor somewhere, who owes me a favor, who doesn’t like me, even though this piece is perfect for them. There’s just a lot of high school stuff, unfortunately, that really deeply influences the freelance market for writing.

So I certainly haven’t found the right lane. I think in a bigger picture sense, I don’t know. It’s a very real concern to me that most cities don’t seem to be able to sustain a local newspaper anymore. There were fundamental jobs being performed. It’s like the Cincinnati Inquirer, which did a pioneering story about how the Dole Corporation was committing crimes and fomenting violence in Central America. I think the Cincinnati Inquirer is down to six pages a day is the length of the paper.

Paul Jay

Can I add just one final sentence? I’ll make it really short. Yeah, I think what people watching this should do is use people like us on this panel, other sources of analysis and news to help inform you. But we’re not ever in this stage of human history. Is this media going to become influential on a mass scale? It ain’t happening.

So what needs to be done is take and get what you can from us and then get involved in organizations that are knocking on people’s doors, bypass the bloody media, go talk directly to people and persuade and discuss and listen. There’s organizations doing this all across the country. We aren’t going to break through. Let’s be realistic. It ain’t happening in this stage of capitalism. They know how to keep us in the margins, but they can’t stop people from knocking on doors and talking to each other. So use us to go do that.

Jyotishman Mudiar

Absolutely. I guess if enough of us start doing that and who knows, perhaps on the ground, there is more ground swelling and maybe capitalism, if not is toppled, it is forced to change character to at least make it somewhat of a command economy from this very sort of free range casino capitalism that you say. We’ll have to leave it there. Thanks, Freddy and Paul, for your time. It was wonderful being with you.

Freddie deBoer

Thanks for having me.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Paul Jay is an independent journalist and documentary filmmaker. He is the founder, editor-in-chief, and host of theAnalysis.news, a site of political commentary and interviews. He is currently working on a documentary series with Daniel Ellsberg titled How to Stop a Nuclear War, which is based on Ellsberg’s book, The Doomsday Machine.

Freddie deBoer is an independent journalist based in Brooklyn, New York. He’s the author of The Cult of Smart: How Our Broken Education System Perpetuates Social Injustice, and his newest book is How Elites Ate the Social Justice Movement. Freddie is a self-styled old-school Marxist and writes regularly on his Substack about politics, Marxism, education, police reform and other topics.