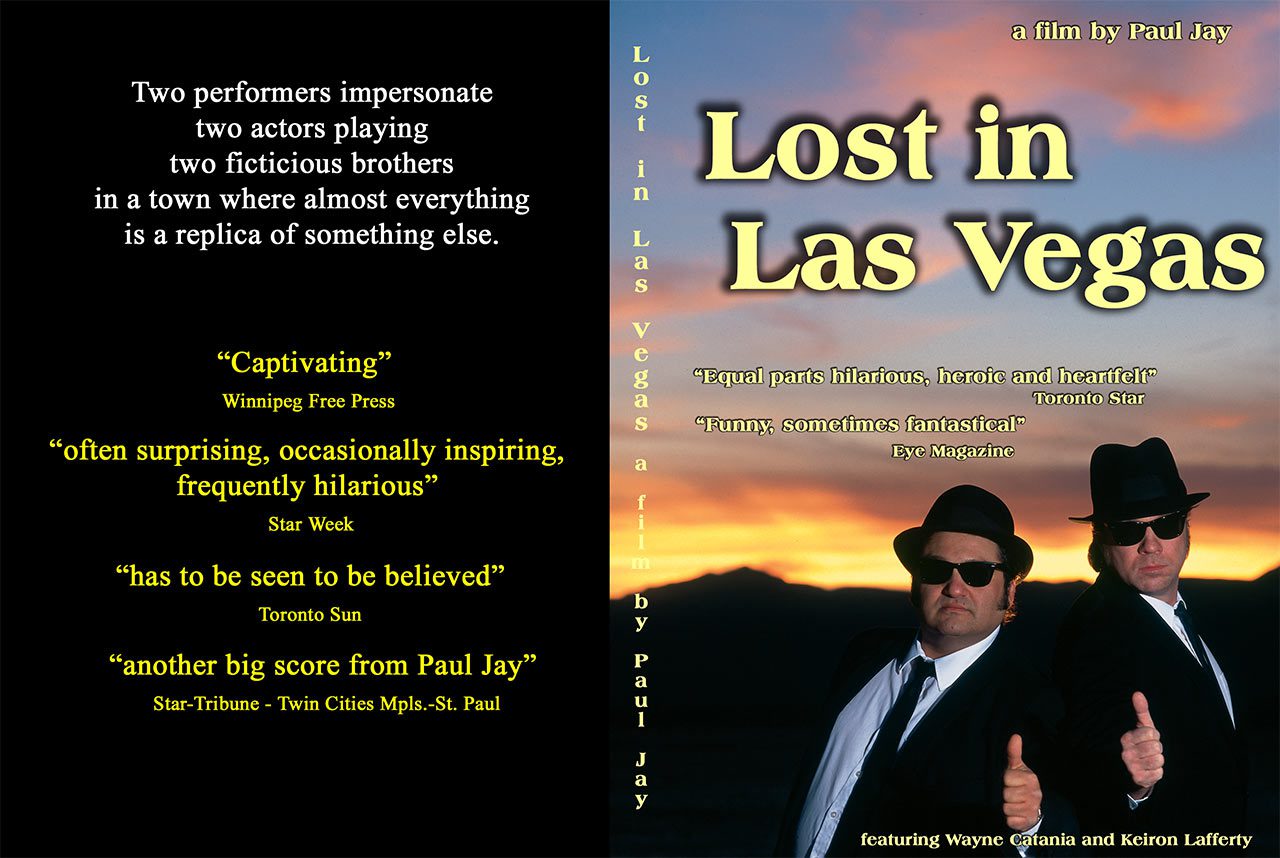

Lost in Las Vegas

Lost in Las Vegas, a film by Paul Jay

Lost in Las Vegas (2001), is the story of two performers who impersonate two actors playing two fictitious characters exploring a city where almost everything is a replica of something else. From New York City, complete with a Brooklyn Bridge and Statue of Liberty – to Camelot, Treasure Island, The Eiffel Tower, and the Egyptian Pyramids – the only thing real in this town is the exchange of money.

Lost in Las Vegas is a film about reality and fantasy, money and morality, and the price one pays to chase a dream. It tells the story of Canadians Wayne Catania, and Kieran Lafferty, who take their Blues Brothers act to Las Vegas and audition for the famous Legends impersonators show. This begins an Alice in Wonderland journey through Vegas as they decide if they want to live and raise families in a city whose only value is making money.

Along the way, they meet local people from strippers to historians to Afro-American activists to the impersonators of Little Richard, Elvis, and Tom Jones. They tell Wayne and Kieran about life and living in Las Vegas. Our protagonists return to Canada, awaiting the results of the audition. At this point, the film turns on itself, and another layer of fantasy is explored, and subjects are left wondering what’s real about their own lives. Finally, our characters return to Vegas, where they must face a truth about themselves and the city of dreams.

Vegas is the place where the American soul is most naked and extreme. It is America as a stripper, Lady Liberty wearing nothing but beads and feathers. Is it a bizarre distortion of American values, or is Vegas the shape of things to come?

Q&A with Paul Jay (questions by Jason Anderson, Eye Magazine)

1. When did you first become aware of Wayne and Keiron’s act? What were your feelings about impersonation acts then?

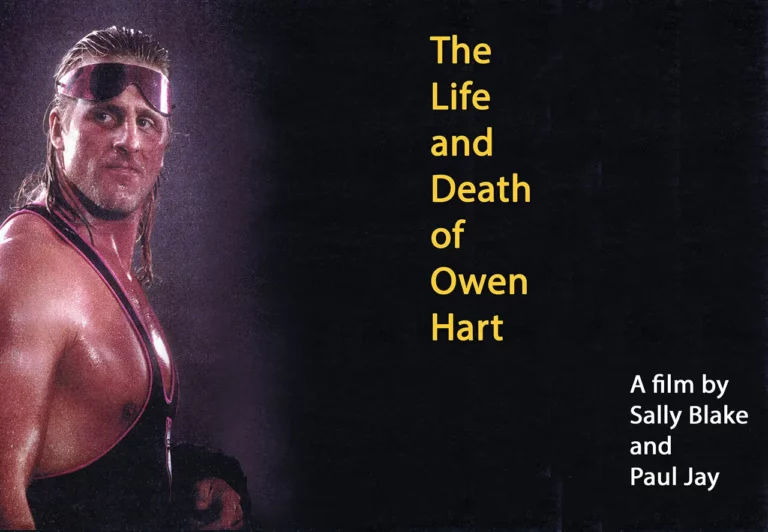

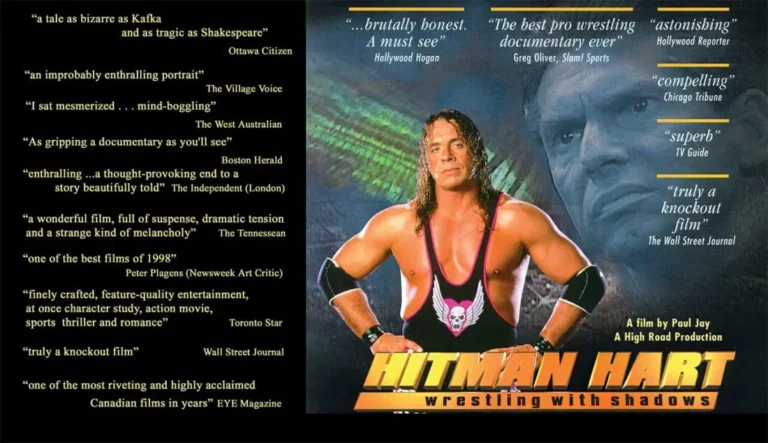

I was sitting in the dentist’s chair and heard an ad for the ‘Legends’ show at the Sheraton in Toronto. Like most of my film ideas, it just felt like it had potential. Before the show, I’d had a kind of snobbish attitude towards impersonators. Very much how I felt about wrestling before I made Hitman Hart. I went to see the show and was quite surprised by how much fun I had and how much the audience enjoyed it. If the impersonators were good enough, people were willing to buy into the fantasy and pretend these performers were the real deal. Wayne and Kieron had the most personality so I decided to meet them. At this point, I was interested, but still not convinced the material was rich enough for a two-hour film.

2. At what point did it seem like their story would be compelling enough to make a film about?

I met Wayne and KIERON after the show and again I was somewhat surprised to find them bright, funny and down to earth. I understood that as subjects they would be reflective, appealing, and KIERON witty and political. I learned about the ‘big’ Legends show in Vegas and the story started to click. Impersonators trying to make the big time in a town where nothing much is real. Vegas as a metaphor for where our society seems to be headed. A social debate about values set against the back drop of the ghosts of cultural icons. A city all about making money and not much else.

How did you pitch it to A&E ?

I spent half a day on the internet looking for background on Vegas. Then I wrote a two page ‘pitch’ document. I write pitches for docs as if they are dramas. I tell a story as if I control the elements as one would in fiction. Sometimes the finished film is like the original vision, sometimes not. While the theme and objectives of the Hitman the proposal didn’t change, the final product was only vaguely similar to the pitch, because when the film began I had no idea Bret Hart and Vince McMahon would go to war. This story took over the film when I was almost finished shooting. In the ‘Vegas’ film, the final product is very close to the original pitch document. Except for the scenes in Toronto when the two guys are waiting to find out if they get the Vegas gig. Here I had no idea what would happen and the way it unfolded was quite surprising.

Anyway, I sent the pitch document to the exec producer at A&E I work with, Amy Briamonte. She also worked with me on Hitman Hart. The pitch was quite wingy, for A&E anyway. How do you make a two hour film with a story as thin as two guys go to Vegas and try to land a job. Anyway, after Hitman’s success, Amy figured if I thought I could do it, I probably could and mostly based on her confidence and the reputation of Hitman she was able to get A&E to go for the film.

It’s very unlike a normal A&E film so I was a little surprised they went for it.

3. They sort of act as surrogate documentarians when they’re meeting people in Las Vegas — how did you come up with the idea of having Wayne and Kieron to serve as both the subject of the film and the quasi tour guides?

It’s a technique I’ve worked out over the course of a few films. I use my subjects to question other subjects, and create a more interesting dynamic. It gives what are inherently static, ‘sit down interviews’ a feel of verité filmmaking, being part of an unfolding story moving through time. For it to work, it has to be justified by something in the ‘real’ story. So it was quite genuine that Wayne and Keiron were struggling with the question of whether they would want to raise their kids in Vegas if they got the job. This justified a quest to find out what makes Vegas tick. I’d throw questions into the mix too. Sometimes you hear them in the film, sometimes not.

4. How did you become interested in the nature of Las Vegas as a city? Was this before you became involved with Wayne and Kieron?

I’d been to Vegas a few years earlier. I knew enough about the place to have an sense of what it was about. Those hours on the internet helped fill out the conception. There were good pieces of social commentary that connected Vegas to the void of values in North American culture today. Vegas as the ‘Statue of Liberty wearing a g-string and beads’.

Flying into Vegas to shoot, I was struck with how it is surrounded by this vast and beautiful desert. This gave me the visual motif I was looking for. The desert became the symbol of what’s real in the world and opposed to the fakery of sin city.

5. How did you go about finding people to provide interesting takes on Vegas life?

Mostly I get lucky. I had a notion of the kind of people I wanted. Sometimes I just ran into them. The guys in the Sand Dollar Blues Bar I met just visiting the bar. Rhonda K. was a friend of Charlie Tuna, one of the musicians at he bar. I found a great researcher, Kurt Coleman, and he found the professors who defend ‘the city of freedom’. The black activist I found doing an internet search. The Elvis impersonator, Graham Patrick, took me to a strip club and we ran into Donna who was a friend of his. And so it goes.

The process of finding the subjects, and making the film itself, is about 40% rational and 60% intuitive. It gets more rational as I get into the edit room.

6. What are your own feelings about Las Vegas now? Do you feel like it’s a straight-up dystopia, like a nightmare of capitalism run amok, or is there something exciting and irresistible about it?

One of the themes of the film is whether Vegas is an anomaly or the shape of things to come. One of the professors in the film says Vegas isn’t becoming more like America, America is becoming more like Vegas. I think that’s true, and it can be said increasingly about Canada too. Corporate values are taking over all other values.

Exciting and irresistible? No, I’ve seen how the ‘trick’ is done, and it’s lost what ever allure it had for me. On the other hand, I met some wonderful people in Vegas, who have become friends. I’ll go back to visit them and spend time in the desert.

7. I love how the film illustrates the sacrifices creative people will make in order to live out their dreams but how the dream may in fact end up kind of distorted, i.e., to live out the dream of playing music professionally, they work in a celebrity impersonation show. Is this the fate of most creative people in Las Vegas or, indeed, anywhere?

In Vegas you find so many talented people going to waste. One of the dancers in the film talks about living a dream, dancing professionally, and then describes their role in the casino as a ‘write off’, meant to attract people to the tables. Some of the victims of Vegas are the people who go there to work in the entertainment industry. People of talent, who mostly find the way to earn their living – as one of the characters in the film says – selling their ass, one way or the other.

Kitchen workers, waitresses and cleaners have a very strong union in Vegas. They get decent pay and benefits. Performers have no union, and unless you’re a star, you get paid dirt and treated like fodder. A ‘Legends’ dancer working two shows a night, six days a week plus rehearsals, makes six hundred dollars a week. Other dancers make less. Remember dancers have a limited working life and are often off injured, without pay. There is such a large pool of talent attracted to Vegas that without a union competition keeps wages down. The casino’s take advantage of the fact that talented people ‘need’ to perform, to express themselves.

There are no publicly supported arts in Vegas to speak of – there’s hardly a public sector at all.

Most of the impersonators in the film are very talented and very frustrated performers. They haven’t been able to make a living ‘doing themselves’, and fall into the ‘Legends’ gig. Keiron Lafferty, one of the Blues Brothers impersonators featured in the film, is a very talented musician. In fact, he wrote the music for ‘Lost in Las Vegas’. Still, in spite of his talent, he struggles to make a decent living. In the film he expresses the dilemma of choosing between his art and making good money in Vegas.

There is risk in being true to oneself and one’s talent. And so it should be. Society does not owe a living to everyone who wants to perform. But when someone has real talent, it’s a pity that increasingly, unless you are a ‘star’ and get packaged and sold with the enormous marketing muscle of a major corporation, there is no way to make a decent living as an artist.

Without public support, artists and performers must adapt to pure commercialism to survive – at least if they want to raise families. Vegas is an extreme example of this model, but again, is that where we are all headed?

8. I also loved the last sequence with the blues musicians, and just the sense that the lives of none of these people are untouched by grief. Did you want to convey some “real” sense of what the blues could be about it, without resorting to the usual cliches? That the ersatz blues of a Blues Brothers impersonation act could somehow be made true?

The ‘Blues Brothers’ act is a homage to the blues, but also a caricature. Genuine ‘blues’ is about sorrow, about the heart. It’s about losing the ones we love, and facing the harsh realities of life. Everything that Vegas culture isn’t. Vegas is a con, a fantasy to make people part with their money.

One of the blues musicians in the scene, Doug Stiegerwald, tells us of the profound grief he felt after the death of his wife. He says that expressing himself through music and the love of his friends, gave him a reason to live. He found life wasn’t’ about getting rich and famous. Blues music is the antitheses of corporate values, it’s about being human.

9. How much did Legends in Concert try to influence the movie and when did it become clear that they were in effect ‘staging’ events for the possible benefit of the film? Did that surprise you?

It didn’t surprise me. Vegas is about promotion. I guess I can’t complain too much about it. If everything wasn’t about selling, I guess they wouldn’t have agreed to the intrusion of the film in the first place.

10. Did you have many qualms about entering the film yourself? Did you try to avoid it?

Yes, I hesitated to do it. In the end, I couldn’t avoid it. There was no other way to truthfully tell what was going on. The subjects turned the filmmaker from an observer into an active player. Perhaps we filmmakers always play this role. In a film about layers of reality and fantasy, I was happy I could expose the extent to which a documentary film itself is contrived and artificial. In fact, I played with this notion throughout the film. Who ever heard of a dream sequence in a documentary?

Toronto Star – Equal parts hilarious, heroic and heartfelt

Eye Magazine – Funny, sometimes fantastical

Globe TV – A Vegas we’ve never seen

Winnipeg Free Press – Captivating

Star Week –Often surprising, occasionally inspiring, frequently hilarious

Globe & Mail Review – New, trippy documentary

Toronto Sun – Has to be seen to be believed

Star-Tribune – Another big score from Paul Jay

Educative article, learned a lot. So glad I found your blog,

and managed to learn new things. Keep posting informative articles, it is really helpful.

Best regards,

Abildgaard Dencker

Just watched “Lost in Las Vegas”. It’s a superb film which approaches its subject- late capitalism- from a human perspective. Las Vegas stands for everything, and ultimately nothing. Thanks, Paul, for posting your superb archive here.