Colleague of Imprisoned Boris Kagarlitsky on Russian Anti-War Opposition – Anna Ochkina

Anna Ochkina is a Russian sociologist and colleague of Marxist sociologist and dissident Boris Kagarlitsky, who has been held in prison by Russian authorities since July 25. She says the authorities don’t actually believe he is a terrorist threat, but it is fear among the elite of his anti-war activism that led to his arrest.

Free Boris Kagarlitsky – Katrina vanden Heuvel

Russian Anti-War Activist Arrested – Boris Kargarlitsky – Paul Jay

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, I’m Talia Baroncelli, and you’re watching theAnalysis.news. Today, I’ll be joined by Russian sociologist Anna Ochkina, who’s also a colleague of Dissident, and Marxist sociologist Boris Kagarlitsky, who’s been in prison since July 25.

If you’d like to support us, to help us continue doing this work, you can go to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Get on our mailing list so you’re updated whenever there’s a new episode, and like and subscribe to this podcast wherever you listen to your podcast.

See you in a bit with Anna Ochkina.

Boris Kagarlitsky is a well-known Russian Marxist, sociologist, activist, and organizer. Over the past few decades, he’s been working towards building a progressive movement in Russia, and he’s no stranger to being arrested. He was a political dissident in the Soviet era and was arrested under [Leonid] Brezhnev following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. He was also arrested under [Boris] Yeltsin. And, of course, he was arrested numerous times by Vladimir Putin’s government for his opposition to Putin’s repressive tactics.

He’s been arrested most recently on July 25 by Russian authorities who claim that he has been supporting domestic terrorism. So Boris has been vociferously voicing his condemnation of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in English-speaking media, as well as in Russian articles which he was publishing. Of course, ever since he’s been arrested, he hasn’t been able to continue with the publication of those articles.

On the same day that his house was searched, the house of his colleague, Anna Ochkina, was also searched by Russian authorities. Two days later, she had to leave Moscow.

I’ll be speaking to Anna Ochkina today to speak about Boris’s views on Russian society and the war in Ukraine and whether she shares the same sentiments.

Joining me now is sociologist Anna Ochkina, who is the former head of the Department of Methodology of Science, Social Sciences and Technologies at Penza State University in Russia. She also taught for many years alongside Soviet-era dissident Boris Kagarlitsky, who is currently imprisoned. She taught together with him at the Russian Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, where they taught on issues of the welfare state.

Thank you so much for joining me today, Anna.

Anna Ochkina

Thank you for interviewing me, Talia. I’m glad to be here with you.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, Anna, on July 25, Boris Kagarlitsky was arrested, and your house was also searched on that day.

Can you speak about why Boris was charged with supposedly supporting domestic terrorism, why you think he was arrested, and why they also searched your house?

Anna Ochkina

I must admit right away that it was a big surprise for me. I absolutely did not expect it. Although, of course, we should have been prepared for this. By the way, we talked about this with Boris more jokingly, but really, we were not prepared seriously. However, Boris has always been very careful in his statements. Just like me. I worked at a state university until the end of August this year, and I had to follow certain restrictions. We consistently stated our principled position but did not transgress a certain line. We have always been quite discreet in the wording. And yet, in the end, Boris was arrested.

On the 25th of July, not only were Boris and I searched, but also the people who, together with him, created and developed his YouTube channel Rabkor. Of course, immediately after Boris’s arrest, there were many versions of why this happened.

The most obvious and simple assumption was that the Russian state was simply consistently destroying the opposition, any opposition. An example supporting this idea is the recent arrest of right-wing radical Igor Strelkov (Girkin). This version assumed that the authorities demonstrate their impartiality, showing severity towards any opposition, both right and left.

There was another opinion that it was a personal vendetta by someone from the FSB or the military. According to this version, someone from the law enforcement agencies was offended by Boris’s jokes and sarcasm about the unsuccessful [Yevgeny] Prigozhin riot that happened a month before Kagarlitsky’s arrest.

I have my own explanation. I think the fact is that Boris has acquired and constantly strengthened quite a serious influence in various circles that are critically important to the Russian government. These are, first of all, students at prestigious universities who studied Marxism from Kagarlitsky, trusted him, and assimilated his ideas.

Another circle of people on whom Boris had influence were opposition-minded deputies and members of official parties, parliamentary parties. The opposition of these people, of course, is very moderate, modest, but still, they strive for positive social changes. Many such people trusted Boris’s opinion and knowledge and even support him now, after his arrest.

The third group is Boris’s audience; these are freedom-loving people who care about politics. He was gaining a bigger audience; he was gaining more and more trust. I think it was his multi-level and growing influence that caused irritation, maybe even anger of authorities.

In addition, Boris’s supporters’ clubs are working and developing in the regions of Russia. Members of these clubs often invited Boris Kagarlitsky to give lectures and consulted with him about their public and political activities. Thus, Boris’s activity went beyond the Internet.

Talia Baroncelli

Do you think that Boris was potentially arrested by the authorities because of a joke he made about Prigozhin and Prigozhin’s mini coup? Prigozhin, I must say, the head of the Wagner group is no longer alive. He was obviously killed in an airplane accident. Boris, for many years, was speaking at least in English media and speaking out against the Russian government. So why do you think it’s just really right now that he is arrested?

Anna Ochkina

This question is the most difficult for me. Why now? I think the answer lies in the accumulation of a certain fear within the Russian ruling elite. The authorities are not unreasonably concerned that things are not going as expected in Ukraine, and social discontent may grow inside the country. Of course, it is. Most people in Russia do not have a clear political position, but they still notice that everything is not going as planned and not as promised. I think that domestic policy in Russia is becoming and will become increasingly tough as difficulties at the front, problems in the economy, and troubles in foreign policy will accumulate. Those people who have not left the country and continue to criticize the authorities are becoming more and more dangerous for it because, at some point, their criticism may find a response in society, resonating with the growing social discontent.

Talia Baroncelli

Boris Kagarlitsky has been involved in activism for many years. He was arrested in the Soviet era under Brezhnev for being a dissident. He was arrested under Yeltsin and is now arrested under Putin, under Putin’s regime. After all of those years of activism, he decided to campaign and run for the Moscow Duma in 2019. You were involved in helping him with this campaign. Why do you think he felt the need to be a politician and try and change things through traditional electoral politics rather than from the world of activism?

Anna Ochkina

Boris was often accused of cooperating with the authorities or of cooperating with the state. But Boris is a very mature, sensible, and rational politician. He understood that the marginalized opposition, deprived of information and financial resources, could do almost nothing in politics. He tried to use official institutions, legitimate ways to declare his position and influence certain processes in power circles, as well as to support people who shared his beliefs.

Yes, I have also been involved in certain official activities to attract people to my side, to create a critical mass of people capable of making progressive changes, capable of bringing things to an end.

Until February 24, 2022, it seemed possible. After that date, it became clear that nothing could be changed by cooperating with the authorities. And I should note that Boris has never changed his beliefs in this cooperation. He has not deviated from his basic principles. He didn’t do it for any reason, for any money.

Talia Baroncelli

You’re also the editor of the journal Left Politics, and you’ve assisted Boris Kagarlitsky in his work in trying to form transnational networks of solidarity between leftists in the West as well as leftists within Russia. If I understood correctly, Boris also tried to establish connections between leftists in the West and certain, I guess you would call them more progressive forces or politicians within the Russian government. I’m wondering if these particular politicians are still working in the government or if they’ve been rooted out completely.

Anna Ochkina

Attempts to establish contact with progressive forces in the West, even with the Western Left, were made by the Administration of President Putin several years ago. Boris and I participated in one of these projects. But these attempts stopped quite quickly. The projects were closed, even though they promised to be quite successful. The Russian authorities began to lean in their sympathies towards right-wing political forces like, for example, Alternatives for Germany. They began to communicate more with them, with the right-wing political sector.

Talia Baroncelli

You were also involved in a political party, the party Fair Russia. Can you explain why that party’s platform attracted you, why you were involved in it, and what made you resign from the party recently?

Anna Ochkina

I wanted to engage in politics in my region to help people in my native Penza region. I needed certain powers for this. I joined the Fair Russia party to use its political resources to use official ways to promote progressive social change in the region. The Just Russia party seemed to be close to the image of the Social Democratic Party, at least for a short time it was such.

I never considered the LDPR (Liberal Democratic Party of Russia) because it was the party of one person, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, and it resembled more of a commercial project. It didn’t meet my goals. I couldn’t join the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (KPRF) because of the Stalinist position and the authoritative policy of the leadership. So my choice fell on the Just Russia party. However, immediately after the start of the war, both the Fair Russia Party and its leader, Sergei Mironov, supported the invasion of Ukraine. In this regard, I left the post of the head of the regional branch of the party and then terminated my membership in the party.

Talia Baroncelli

We’ve already discussed that Boris was charged with committing domestic terrorism in Russia by the Russian authorities. Would you say that any sort of opposition to the war in Ukraine is considered by the Russian authorities to constitute domestic terrorism? Would people who oppose the war be at risk of being imprisoned for domestic terrorism?

Anna Ochkina

I don’t think that any of the FSB people, Russian judges, or all those who make decisions on political charges really believe that the venerable professor from Moscow is a terrorist, an extremist, or even justifies terrorism. Boris is accused of justifying terrorism, but two weeks after his arrest, he was included in the list of “terrorists and extremists.”

In Russia, there is such an institution, “Russian Financial Monitoring,” which fights against the laundering of criminal money. Rosfinmonitoring also tracks financial interaction between terrorist groups, their supporters, and sponsors. Boris got on this list for no reason. Officials have not provided either him or his lawyer with any explanations, facts, or evidence of his involvement in terrorism. Of course, such facts simply do not exist. It’s just a way to intimidate people who are in opposition, a way to intimidate those who support political prisoners, including Boris. The ruling circles seek to stop the opposition movement and any political activity in the country by any means. “Justification of terrorism” is just words, just a pretext, and even those who accuse Boris and keep him behind bars understand this.

Talia Baroncelli

Vladimir Putin continues to describe this military operation as a special military operation. He hasn’t declared a full-scale mobilization in Russia. Why do you think he’s using this particular language and refraining from declaring a full-scale mobilization?

Anna Ochkina

I think that the Russian authorities are making a lot of effort, and they should make much more effort to avoid а full-scale mobilization. I assume that the ruling circles are aware of their inability to cope with this task to organize everything properly. А full-scale mobilization implies the need to manage large traffic flows, the need to accommodate, feed, train, and provide uniforms and weapons to huge masses of people. It is also necessary to organize the smooth operation of recruiting stations.

But Putin’s state system is very inefficient; it is not ready for such challenges, for such large-scale tasks.

So they decided to do something else. A year ago, a partial mobilization was carried out, which primarily affected poor regions, and during which quite large payments were also promised to the military at the fronts, significant bonuses to soldiers and officers in case of combat injury and payments to families in case of military death, payments that seem huge by the standards of the Russian province. So, the state decided to just buy people for the battlefield. The state is trying to attract more and more military personnel on a voluntary basis, promising significant salaries and large compensations to families in the case of their deaths. And as long as the state somehow fulfills its obligations, everything is going more or less well.

However, there is already quite a lot of evidence that the state does not always fulfill these obligations. Videos with military people complaining about poor provision of food and ammunition get on the Internet from time to time. Cases where military families have not received the promised compensation also sometimes become known, although reports of this can not always be confirmed.

Talia Baroncelli

With regards to people volunteering to join the Russian armed forces and to fight in Ukraine, we’ve seen many young men from poorer regions of Russia, particularly areas in which there are other ethnicities, join the army. I’m wondering if these people are joining out of a sense of desperation and monetary need. Or would you say their motivation is that of patriotism and a sense of nationalism?

Anna Ochkina

This is a very interesting question: patriotism or money? Some time ago, a funny advertisement was shown on Russian television. The videos had different plots, but the slogan was the same: go to war in Ukraine, you will receive a decent salary, a wound will provide you with a solid bonus, and in the event of your death, the state will provide your family excellently. Go to war, and you will be rich and happy. Russian official circles denied their involvement in the creation and distribution of such advertising. Nevertheless, the policy of the Russian state now is exactly this – to bribe people to send them to the battlefield.

There are sociological studies, however, not very large-scale but indicative. There are interviews with men who went to war voluntarily or as mobilized. All these interviews show that money is much more likely than patriotism to motivate people to go kill and die. People say in interviews that they are very happy to be able to help their families, to become real breadwinners. They are not afraid to die, knowing that their families will finally get rich and the state will financially support them.

What are these payments for which people could risk their lives? A soldier on the battlefield receives a salary of 200,000 rubles per month (approximately $2,000), which is three times the average salary in Russia. For poor regions, for small towns, and for rural areas, these are astronomical sums. Injury on the battlefield is compensated by the amount of three million rubles (about $30,000 US) are brought to the fighter, and in case of death, the family receives 5 million at a time from the federal government, 1 or 2 million from the regional administration and 3 million as insurance payments. Of course, 5 million rubles is $50,000. The amount may not be impressive for Westerners, but this is the cost of a one-bedroom apartment in a provincial Russian city.

That’s why men said in interviews: I’m doing this for my family; I could die for a reason. After my death, my family will get rich, so my life will finally make sense. I will not die in vain.

Some time ago, my classmate, the famous economist Vladislav Inozemtsev, published an article in the Insider, “The Economy of Death.” In the article, he shows that if we take into account the entire amount of state financial support to the people fighting in Ukraine, it turns out that every military man, if he dies no earlier than six months after coming to the battlefield, will receive for himself and for his family an amount that the average Russian worker cannot earn in a lifetime. So yes, the Russian authorities decided to buy people who are ready to kill and die.

Talia Baroncelli

I wanted to ask you about the conditions in the areas in which many young men are joining the war. Would you say that they are more rural areas? Areas outside of the city that are potentially more besought by poverty sort of post-industrialized spaces. Would you say that there are other job prospects in these areas?

Anna Ochkina

The Russian authorities organized last year’s partial mobilization quite cunningly and inventively. Most of those mobilized came to the battlefield from remote regions, Siberian regions, and regions with depressed, weak economies. Partial mobilization primarily affected people from small and poor cities, as well as from rural areas.

The people who volunteer for the war today are men who had no prospects of getting an education, an interesting profession, or finding a good job in their city or village. Most of the people who go to fight voluntarily in Ukraine today are people from poor families, from poor regions. Mobilization and war did not unite Russian society but, on the contrary, aggravated social inequality. Some left the country after the mobilization began, and some stayed and went to war, most often simply because they were too poor to leave and ignore the financial benefits promised by the state.

Talia Baroncelli

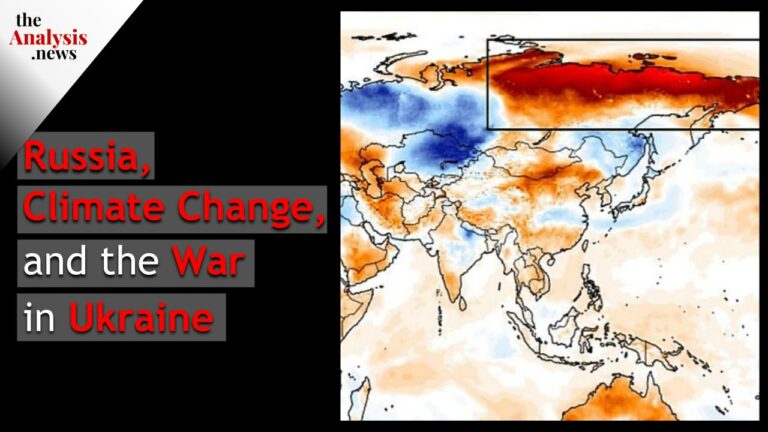

So many people on the Left, particularly in the West, argue that the reason for this war is because of NATO’s enlargement and encroachment of Russia. Whereas Boris would often argue that the reason or motivation behind invading another sovereign country, that being Ukraine, was for purposes of domestic politics to serve as sort of a tool of domestic politics to perhaps distract or create another narrative as opposed to focusing on the problems at home. Do you share this perspective with Boris?

Anna Ochkina

I have always agreed with Boris that the reasons for Russia’s invasion of Ukraine were exclusively internal; these reasons are related to the complexities of domestic Russian politics. From a certain point on, the Russian government stopped coping with its internal contradictions and decided to shift the focus of attention of both the elite and society from internal threats to the outside, as if taking the contradictions out of the country.

The contradictions that had matured within the Russian elites and society by 2020 related to the upcoming presidential elections in 2024. The question of Putin’s leave arose because, according to the Constitution, Putin could not run in 2024. There was no agreement among the elites as to whether Putin would remain president or leave. This upset the balance within the government and threatened the stability of the political process. Finally, it was decided that Putin was leaving his post, and the search for a successor began. It seemed that the process of transferring power in Russia had started.

But suddenly, something changed, and the process contradicted the original plan. Some of the elites insisted that Putin remain president. The Constitution was urgently changed. Amendments to the Constitution were planned earlier, and the presidential lawyers worked best on the article on guarantees to the outgoing president. This suggests that Putin himself was going to leave his post but then changed his mind. And articles were hastily added to the Constitution, lifting the ban on Putin from running again.

There was an event that in Russia was called zeroing. That is, it was decided that from 2024, Putin’s presidential terms will be counted anew, and he will be able to run for president in both 2024 and 2030.

Putin stayed, but there were also problems, social and economic. The Russian economy is part of the global economy, and Russia’s economic problems have been accumulating since the global crisis of 2008; this crisis has not been overcome, it has only been mitigated with the help of public money. The COVID pandemic has also hurt the Russian economy.

Unresolved internal contradictions forced the Russian authorities to launch an invasion of Ukraine, hoping in this way to find a solution to internal problems, problems on the world market.

Talia Baroncelli

Yevgeny Prigozhin, the former head of the Wagner group before he was killed in an airplane crash, released a statement that questioned the aims of the war in Ukraine. A lot of what he said was in contradiction with the official Russian narrative. He was basically saying that NATO did not really pose a threat. That was not the reason why Vladimir Putin went to war. He was also saying that the Russian military was not properly equipped to fight the war and that it needed more resources, and he was calling for martial law and full mobilization. Obviously, he was also calling for more people to join the war effort and to have more military equipment and those sorts of resources. His statement seemed to be a bit contradictory because it was saying the reasons for going to war were not correct or based on false assumptions, but that they should now ramp up the war effort and continue the war. Do you think a lot of Russian elites support the view of the former head of the Wagner group?

Anna Ochkina

I am sure that a certain part of the elite and people in the armed forces or in the FSB shared Yevgeny Prigozhin’s point of view. They could not help but see problems on the battlefield, failures, and errors in the management and supply of troops. They understood what Yevgeny Prigozhin was talking about, shared his conclusions, and sympathized with him. But they weren’t organized enough to support him openly.

We do not know what would have happened if Yevgeny Prigozhin had reached Moscow, whether he would have met support or resistance. But I am absolutely sure that his criticism of the Ministry of Defense aroused sympathy and approval, and this is understandable since part of this criticism was actually true. Of course, the reasons why Prigozhin shouted his curses and threats were neither altruism nor pacifism. Prigozhin was part of the system that ruined him. And Prigozhin is responsible for all the sins of this system.

But still, part of Prigozhin’s criticism was fair and correct. I think that many people in the government and in military circles shared these views in their own way.

Talia Baroncelli

I’ve heard some Russian policymakers and academics speak about something called state civilization. They see Russia as constituting a state civilization that holds specific values and norms that are not necessarily aligned with those of the West. Whether we actually want to espouse so-called Western values or not, it can be a different discussion, but they see that the sort of international order of the West is at odds with their own values and that they try to see their future as being aligned with the East and particularly with China. Could you explain what is meant by state civilization? How does this concept function in a lot of the political discourses, and whether you think it’s something that should be supported?

Anna Ochkina

Today, the theory of civilization is very popular in Russia. The course “Fundamentals of Russian Statehood” has been introduced in universities since September 1 of this year. This course contains a section dedicated to the values of Russian civilization. President Putin last year approved by his decree a list of Russian traditional values. Then there is all this value of human life, the dignity of honor. The same presidential decree on traditional values notes that the enemies of Russia’s traditional values are Western countries, especially the United States of America. The idea that our country is in a constant state of war with the West is very popular in Russia today. Russian propagandists call this war a war of values and a war of civilizations. However, all these conversations are just a cover for aggressive foreign policy and repressive domestic policy. The Russian state got along well with the West when the Russian elite had enough resources and when there were no such economic contradictions. I am sure that it will be the same in the future when this crisis is overcome.

There is no conflict of values or civilization here. The imperialist states are fighting for supremacy. Russia is not fighting imperialism; it is fighting for imperialism with itself at the head. Russia today hopes to get China, African countries, or Latin American countries as allies. But the people of these countries hope in vain that Russia will protect them from imperialism, protect them from poverty and suffering by imperialist exploitation.

Talia Baroncelli

When Putin came to power, he was able to gain the support of the existing oligarchs by promising that the oligarchs would be able to retain their wealth and their assets, especially all of the resources they had privatized and the companies they had. They would be able to continue to engage in their business dealings. In return for that, the oligarchs would promise not to get involved in politics. They would essentially obey Putin’s political agenda and follow his political ideals. Do you think that the current oligarchs fall in line? Are they still intent on respecting Putin’s foreign policy and domestic policy agenda, or are they starting to look for other masters, so to speak?

Anna Ochkina

I think that hopes for an uprising of Russian oligarchs against Putin are groundless. This hope does not become more justified despite some statements by representatives of the Russian oligarchy.

Yes, even Oleg Deripaska, loyal to the regime, once said that not everything is going as it should. Yes, among the oligarchs, you can notice some fear and anxiety. From time to time, the Russian press has published some critical statements of the oligarchs, but they are very rare and timid.

Russian oligarchs are too afraid of each other and too distrustful of each other. In addition, Russian oligarchs are tightly tied to the current Russian regime with all kinds of obligations, crimes, and violations. Therefore, the oligarchs cannot seriously oppose the existing Russian regime. Some of them will run away and try to make a new life in the West; I can imagine that. But I cannot believe in the unification of Russian oligarchs against the regime that spawned them.

Talia Baroncelli

Boris often speaks about Russian society, calling it incredibly atomized. He says that it’s even more neoliberal in a way and more individualist than some other Western societies, arguing that people are much more concerned with their personal lives, with their family lives, with just surviving, and that they’re not really interested in politics. There’s a disinterested sense or indifference even towards the war. Would you say that this characterization of Russian society as being incredibly atomized is accurate, or is it a bit unfair?

Anna Ochkina

Boris and I have had quite a few joint projects. We also carried out sociological projects using the method of focus groups, large-scale questionnaire surveys, and analysis of various sources.

Unfortunately, these studies have convinced us that Russian society is apolitical and Russian citizens are very passive politically.

Russian citizens often know nothing about politics and do not know the names of politicians, even the names of their representatives in federal and regional parliaments, in municipal councils. Most Russians do not fully understand the differences in the status and responsibilities of federal and regional parliamentarians, municipal deputies. Russians don’t care about that. Russians are not interested in political processes. They need people who will solve some everyday problems, repair roads, roofs, paint houses, and so on.

Most Russians are focused on their personal life, on solving everyday problems, on the well-being of the family: how to make money, buy an apartment, renovate and decorate it, buy a car, how to raise children, help them, give them a good education, and so on. The inertia of avoiding politics and rejection of political activity is very strong in Russian society. Russian society is a very disjointed society. Russian society is experiencing an acute lack of solidarity. However, Boris has always said that things can change very quickly when people begin to feel that their daily life is not going as they should because of the accumulated problems unsolved by the state.

However, Boris believed that at some point in time, the masses of people in Russia would become politically active. These will be the same people who are now only interested in their private lives, looking for information on the Internet only about fashion, fishing, or cooking. I’ve always been more pessimistic. I thought that such a transformation, unfortunately, would happen only after some huge tragedy that Russia would go through. This tragedy still seems very likely to me.

Talia Baroncelli

We started the interview by speaking about Boris Kagarlitsky and his arrest. I was wondering how long do you think he will be held by the Russian authorities? They did say that he could be held for five to seven years. Do you think this is likely or that it could be longer? What do you think will come out of his trial? Will it just be more falsehoods about him supporting, quote-unquote, domestic terrorism?

Anna Ochkina

The punishment for the crime Boris is accused of, that is, justifying terrorism using the Internet, is either a huge fine or from five to seven years in prison.

Boris has been in custody since his arrest, and the court has consistently refused to release him under house arrest.

Such a situation, according to Russian legal practice, is often a sign that a person will not be released after a trial and will probably receive some time in prison. What will be the verdict? I cannot and do not want to predict. The investigation of Boris’ case has now been completed. He remains in custody until November 24. He has already read all the documents on his case. Right now, we are just waiting for the trial date to be set. I really hope, contrary to various signs, that there will be no imprisonment.

Talia Baroncelli

We’ve seen Western media largely overplay military gains made by the Ukrainians, and I’m sure Russian media is downplaying a lot of the losses on the Russian side. What do you think will lead to an end to this war? Will it be military gains on the battlefield, a potential ceasefire negotiated by other powers such as China or even Turkey, and obviously, with the involvement of the United States? Or will it be up to different political groups and an organized movement within Russia, people rising up or opposing this war for both ethical reasons as well as economic reasons and fear for the future of their country?

Anna Ochkina

It is very difficult for me to predict anything about the future because I have a pessimistic view of the future, and I don’t want to talk about very pessimistic scenarios. But it seems to me that, after all, the future will depend on events inside Russia. Although many analysts think the opposite way and believe that everything will be decided on the battlefield. But no, based on the current state of Russian society, everything will depend on how strongly Russians want changes and how resolutely they will be able to fight for them.

If society continues to show passivity, these changes, unfortunately, will occur only as a result of some gigantic social explosion or a huge social tragedy. Boris was more optimistic than me. He believed that, yes, Russia would face roaring years, radical social changes that would eventually determine the outcome of this conflict. He was optimistic about these changes and believed that they would eventually lead to progressive democratic change.

But I also want to hope that, one way or another, Russia will find a way to its democratic future.

Talia Baroncelli

Boris Kagarlitsky was very optimistic when it came to the future of Russia and the Left in Russia, to a progressive movement in Russia. Do you share that same sentiment? What are your hopes for Russia and for the Left? What do you think will happen?

Anna Ochkina

I would like to share this optimism and support Boris in his actions, just like the people who have been working with him all these years. I share this optimism in my work. Doubts remain with me in my soul.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, Anna Ochkina, sociologist and former professor at the Russian National Academy, as well as Penza University in Russia. Thank you very much for taking time today to speak to me, and I really appreciate all of your time.

Thank you for watching theAnalysis.news. If you’re in a position to donate to the show, please go to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. That way, we can continue making the content. See you next time. Bye.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Anna Ochkina, Russian sociologist, is the former Associate Professor and head of the Department of the Methodology of Science, Social Theories and Technologies at the Penza State University (Russia). She is Deputy Director of the Institute for Global Research and Social Movements (IGSO) and deputy editor of the journal Levaya politika (Left Politics).