Defunding UNRWA to Starve Gaza – Sari Hanafi part 2/2

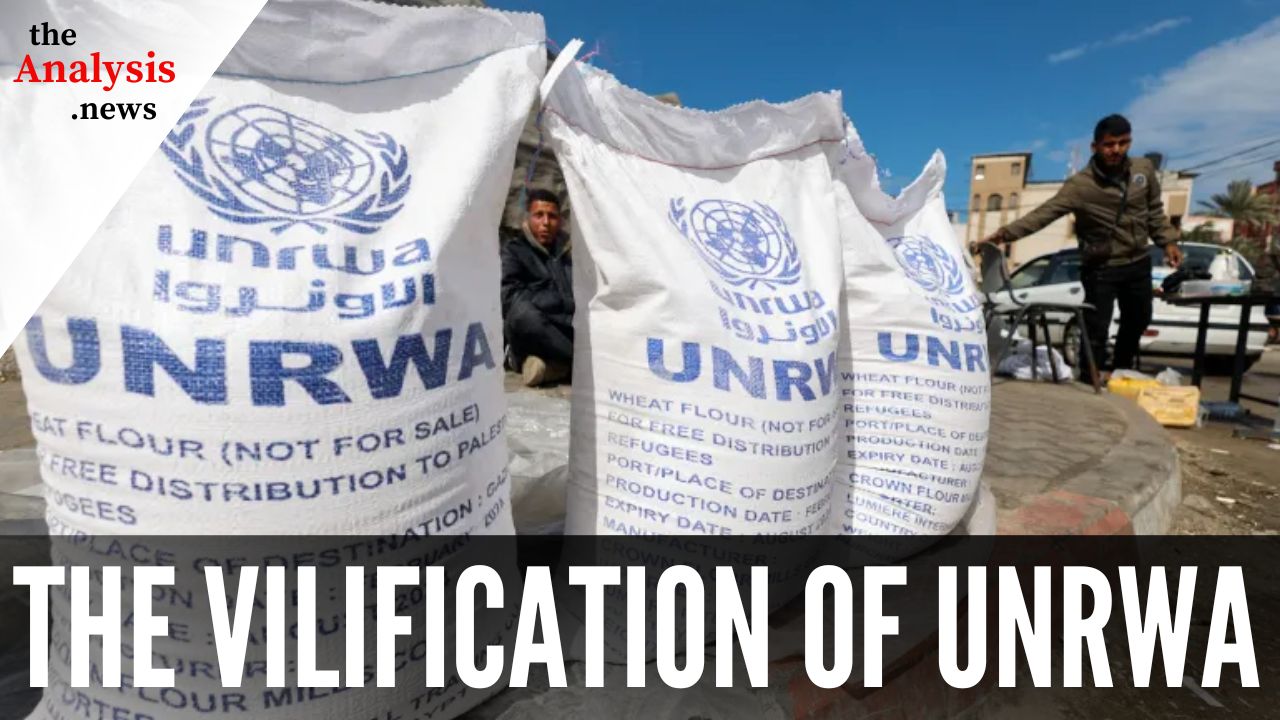

Israel’s accusations against a total of 19 UNRWA staff members alleging their involvement in the October 7 attacks prompted 16 countries to pause or suspend $450 million in funding to the agency. A UN investigation resulted in one of the 19 cases being closed and four suspended due to a lack of evidence. Of the 12 staff members initially accused by Israel, 10 of them were fired by UNRWA, while the other two were killed. Israeli claims that 10% of UNRWA employees have ties to Hamas have yet to be substantiated. As Sari Hanafi explains, UNRWA provides critical infrastructure, housing, and education to Palestinians in Jordan, Lebanon, the West Bank, and Gaza.

Selective Outrage: Why the Slaughter of Palestinians is Ignored by Western Governments – Sari Hanafi part 1/2

Talia Baroncelli

Hi, you’re watching theAnalysis.news, and I’m your host, Talia Baroncelli. This is part two of my conversation with sociologist Sari Hanafi. If you enjoy this content and would like to help us out, you can go to our website, theAnalysis.news, and hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen. Make sure that you’re on our mailing list; that way, you receive a message every time we release content and publish episodes. You can also like and subscribe to this show on YouTube, Spotify, Apple, or wherever else you watch or listen to the show. See you in a bit with Sari Hanafi.

Joining me now is Dr. Sari Hanafi. He is a professor of sociology at the American University in Beirut, and he was previously the editor of Idafat: The Arab Journal of Sociology. He was also formerly the President of the International Sociological Association. He has written numerous articles on the situation of Palestinians in the refugee camps in Lebanon, as well as analyzing the various tactics used by Israel in its occupation and spacio-cide of Palestinians in the West Bank and in Gaza. He’s also written on the role of religion and religiosity in Arab societies. Thank you so much for joining me today.

Sari Hanafi

Hello, Talia. It was a pleasure to be with you.

Talia Baroncelli

It’s great to have you. I definitely wanted to ask you about UNRWA, which is the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, which provides services to Palestinians not only in the occupied territories but also in refugee camps in Lebanon and in Jordan.

I think it’s worth noting that UNRWA was created in 1949 and then made operational in 1950, before the Geneva Conventions on Refugees. Before the whole idea of giving the right to asylum to individuals was conceived by the international community or by at least the countries at the time who were considered to be nation states and who could make the legal decisions on the international stage. As a result of this, it means that Palestinians can’t get any protection or assistance outside of the UNRWA framework, meaning that they can’t just go to, say, a European country like Germany or Italy and apply for asylum as other asylum seekers would. They’re not entitled to the same international protection that, say, a Syrian asylum seeker would be. They can’t apply for asylum under the Refugee Convention of 1951. Some people argue that this reproduces certain inequalities of access to international protection, and this is all tied around the conditions of the right to return.

Aside from that, how would you say that Western institutions and Israel and the United States in defunding UNRWA are actually actively starving the Palestinians because of the very important role that UNRWA has traditionally played on the ground?

Sari Hanafi

It’s an excellent question. I would say it is exactly like October 7. The resistance’s actions, with its atrocities that morally we can criticize, cannot be understood as a gang that invaded a place. No, you understand it if you start thinking from 1948 of this apartheid state, about this settler colonial state, particularly since 1967 and so on. It is the same thing I would say for UNRWA.

There has been a protracted campaign against UNRWA from Israeli authorities throughout the last 30 years. Again, why 30 years? It’s a slow process. It’s a time where the Israelis were afraid of anything that imposed a solution for the refugees. What Israelis wanted to do is eliminate the question of refugees. For the Israelis, there is no refugee problem.

If you want to open two brackets, I do remember a friend of mine, an Algerian who was an important officer, the head of Cairo office for UNHCR, who told me, and sometimes in a cynical way, “Look, an African can come to Cairo, and we can help him, but we cannot help a Palestinian in Egypt whose basic rights has been deprived for the last 30 years or 40 years.” Again, why I said sometimes cynically, because as an Arab nationality, they think that giving the Palestinian any civil rights would undermine their right to return. This zero-sum game, if you like, equations, which is a stupid equation, absolutely. We can have socioeconomic rights, we can have a passport, and live properly, but at the same time, we don’t have the possibility of claiming the right of return.

To close this paragraph, UNRWA is really what you, Talia, tried to say; it’s become a raison d’être for the refugees. It’s an inherent part of their identity. Eliminating this will eliminate the identity of a Palestinian refugee.

Israel grabbed this occupation of Gaza and the solidarity of all this politicking of the political class in the West and said, “Let us do things we could not do in the past.” Massive killings in the West Bank. Always, you see how funny Europe and the United States are. They put three or four settler names in their release for financial sanctions. What are you talking about? There is deliberate mass killing against the Palestinians in the West Bank. Since October, 460 Palestinians have been killed in the West Bank. Israel, to summarize what I said before, is really targeting UNRWA, at least for the last 30 years, and they want to eliminate this marker of Palestinian identity.

Without talking about how functional UNRWA is in providing education and help for Palestinian refugee problems, people might not know that we have fourth-generation Palestinians in countries like Lebanon, where Palestinian refugees don’t have the right to work or own properties. They are really in a terrible socioeconomic situation. UNRWA is extremely instrumental in that.

If you remember UNRWA during the previous war on Gaza, 2007, 2009, and 2011, UNRWA was in charge of receiving materials and food during the bombardment, but also later on the reconstruction of Gaza. Israel wanted to delegitimize all of the potential actors in the Gaza Strip: Palestine Authority and UNRWA. It means to leave them without governance. Of course, they are dreaming that they will give the power to the tribes. It means that they are really playing on this divide to rule to create tribal authorities. Definitely, it worked. I think, again, the Israelis think the Palestinian resistance can be vilified as one organization called Hamas, and Hamas is composed of a number of people. We kill these people, and we will end this problem. They are dreaming. The Palestine resistance is an idea. Hamas is an idea. It can be regenerated with any actor later on.

Talia Baroncelli

Something that you’ve made clear just now is how, for example, UNRWA is so crucial to having the infrastructure on the ground to distribute aid and not just being this marker of Palestinian identity. Its very existence is based on the right of return. So UNRWA is there to ensure or to advocate, perhaps, for the right of Palestinians to return to the land they were dispossessed from and pushed off of in 1948.

It has a very practical importance on the ground. UNRWA workers were the ones, the local ones, especially, who actually stayed there. The local ones were the people who continued to distribute the aid because there were a lot of foreign UNRWA workers who actually left after October 7. Israel has been targeting civilian officers on the ground and making it very difficult for aid to be distributed. This is why they suggested or imposed on the Palestinians this port in Gaza to bring in aid that way, which is actually not a very effective way when you can just bring in trucks very easily into the Gaza Strip and have UNRWA and other aid organizations on the ground distribute it.

In a way, they’ve fabricated this issue of not being able to have aid delivered properly. I don’t know if you would agree with this, but Netanyahu also did say that the port was built to potentially voluntarily transfer Palestinians out of the Gaza Strip. How do you evaluate this particular tactic? With this tactic of building a port and making it easier to actually ethnically cleanse Palestinians from the Gaza Strip, does this fit in, do you say, to his calculus of trying to get rid of Palestinians, or was this just a band-aid effort to bring aid in the ways that they wanted to bring aid in?

Sari Hanafi

Look, I would say even before Netanyahu, [Yitzhak] Rabin once said that he dreamed one day, he opened his eyes and there was no Gazan people or Gaza was swept into the sea. I think they dreamed that this stronghold Palestinian resistance would be eliminated. If they cannot eliminate it, it’s to transfer the population. Yes, the port can be a way of facilitating this.

I have a colleague, a Western diplomat based in Cairo. He told me, “Seriously, [Antony] Blinken, in the beginning of the conflict, he spouted this Israeli idea of a transfer of population.” They were negotiating with Egypt, the Americans, the financial cost, the compensation, how much they would eliminate from their debt, the international debt that Egypt has, by accepting the Palestinian population in Sinai. It was a serious plan by the Israeli establishment.

I think this Palestinian resistance, the Israeli, in any case, they thought, remember that declaration in the first two weeks where the Israeli Minister of Defense said, “This war is a matter of one month or two months.” Now, we are at almost seven months, and they haven’t eliminated Hamas. Hamas is still the master of the Gaza Strip.

Talia Baroncelli

They also haven’t gotten all the hostages back. Many of the hostages have probably been killed by Israeli bombs or maybe by Hamas as well, we don’t know. But if Netanyahu really cared about the well-being of the hostages and bringing them back, then he would ensure that there would be a ceasefire because we did see that the time in which the most hostages were returned to Israel was when there was a six-day ceasefire.

Sari Hanafi

Yeah, exactly. I think you have this international outrage worldwide in many places, including in the United States, this sanction against Biden from Michigan, for instance, with 100,000 people now uncommitted to the Democratic party. They don’t want to vote for Biden. It changed the direction or the course of the events. I think this is why it’s important what happened.

I’ll give you an example that I wanted to say at the beginning, but I forgot. I was really very positively surprised about the re-election of George Galloway, in one of the districts of London. I looked at his campaign, and it was mainly about U.K. foreign policies and the bias or the colonial nostalgia of the British government. He was elected by 16,000 votes, and the second one who was not elected took half the amount at 8,000 votes, and the third, 4,000 votes. It means that even mainstream British people wanted to say, “No, we want somebody honest in politics to represent us.” This really gives us some hope.

This is why I see the genocidal war on Gaza as not only a game changer for the Palestinian-Israeli conflict and putting the Palestinian issue on the table after this threat of full normalization of many Arab countries with Israel, not only stopping this, but really it’s a game changer about how we can make ethical political actions. It is reconnecting ethics with politics.

Talia Baroncelli

I have so much to ask you still, and I think maybe the next question would be about your research on the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon because I think a lot of people see what’s happening in a sort of vacuum. They don’t really understand the history, and they might not know about the civil war that took place in Lebanon, which was between various factions, but also the Christian Maronites and the Phalangists in Lebanon, as well as various Muslim groups, some groups that were influenced by Syria. Then, you had various Palestinian liberation groups or national liberation groups.

In 1975, there was a horrible massacre in Tel al-Zaatar, outside of Beirut, I think the east part of Beirut, in which there was something like a 62-day siege on the Palestinians there. I believe this siege was led by Christian nationalists, and over 1,500 people, in the end, were actually slaughtered. This took place in a very specific context, which some people call the ‘golden age’ of the Palestinian revolution in Lebanon, from the Cairo Accords in 1969 up until Israel’s invasion of Beirut in 1982.

Could you perhaps explain why that period was so important and how the conditions in the refugee camps then were very different from what you identified earlier in the interview as the unemployment and lack of prospects in the refugee camps in Lebanon today?

Sari Hanafi

Yes, actually, you are right to highlight how Lebanon became very important for the time, for the development, and the maturing of Palestinian National Liberation Movement. The Palestine Liberation Movement, have been located and had it’s headquarter here in Beirut, with all its political and military heads.

Now, unfortunately, with Lebanon, as a mosaic society and with the tension, I would say the Civil War in 1975 is not really only sectarians. There is social class dynamics. There are certain elites who own the economy and distribute the benefits amongst themselves while the other is not.

In this background, Lebanon in 1975 entered into a civil war. Of course, the mighty organized militia at that time was a Christian militia or the right-wing Christian militia. Then, what made the counterbalance was the entrance of the Palestinian factions in favor of the nationalist and socialistic groups in Lebanon. This is where it created problems later on that some Lebanese, let’s say about half of the Lebanese, don’t want to give the Palestinian any rights because they were involved in this. This is half of the Lebanese. The other half was, of course, happy that the Palestinians supported the national progressist movement.

In this backdrop, it became very difficult to advance any form of socioeconomic and civil rights for Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. As I said previously, they don’t have the right to own property, to work, and to compose associations. They are in very slummy refugee camps which lack basic environmental conditions and are very crowded. These camps are one-kilometer square each. Of course, the population is increasing demographically. This is why there is really a real problem today with the refugees in a country like Lebanon.

I think this is why the Palestinians are still seeking a national liberation solution. National liberation that can take the form of a one-state or a two-state solution, and of course, the possibility of the Palestinian refugees to have the choice, if not only, I would say, right of return, but the choice for it to be settled, to be in different countries. All of these dynamics can be unleashed by a national project.

Today, of course, some countries like Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Australia said they are ready to recognize a Palestinian state. Okay, I’m happy about that, but in America today, they tried to say to the Saudis, in the last conversation Blinken had with the Saudis, “What about recognizing a Palestinian state but without borders, without frontier?” Imagine, without a border, it’s nothing.

The whole problem of the Palestinian National Authority is today, they govern small islands, small territories here and there with this integrity. It’s like a municipal power. Without the idea of sovereignty, without the idea of a border, it doesn’t mean a Palestinian state. The question of Palestinian refugees is very important. The Palestinian state should accommodate those who are unable to continue living in these inhumane conditions, like in the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon.

Talia Baroncelli

There are a few things there that I want to pick up on. You’re saying that without borders, without nation-state borders, there could be no sovereignty. But that’s saying that Palestinians can only have independence or some freedom and integrity within the confines of a nation-state. I know that a nation-state, of course, would afford certain privileges and certain securities, but it might not address all of the issues because you already also mentioned the elite structures and neoliberal decision-making in the Palestinian Authority, in different governmental structures. How do you reconcile the two? Could it be possible to have other forms of integrity and independence outside of the nation-state in ways that perhaps would escape neoliberal confines?

Sari Hanafi

Well, in one of my writings, I wrote about what I called the flexible extraterritorial nation-states. Until today, nation-states are not only important for the question of sovereignty. It’s important for the question of citizenship, the idea of being a citizen. Until today, even the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Talia, when you say no discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, thinking that you have a state, a sovereign state, which will enforce no discrimination. Even this idea of humanity, equality, and liberty needs a state to reinforce it. It goes beyond whether this is a communist state, a neoliberal state, or a socialist state. The state is important. We should not throw the baby in the bath water. I think the way nation-states become authoritarian, they become problematic, they become neoliberal, but nevertheless, the idea of a state is important for reinforcing the citizen’s rights.

If you ask me my opinion, I am in favor of finding a one-state solution, Palestine/Israel, for all its citizens. They live here, one man, one vote. Of course, the Israeli Zionist project doesn’t want that. Now, they are veering towards the right-wing side in Israeli society. They definitely don’t want a one-state solution with the Palestinians. In that case, let’s have a two-state solution.

However, within this two-state solution, you can envision the mobility of the population, the possibility of double allegiances, and the possibility of working in some and living in another place. You can mitigate this idea of a nation-state where the territories, people, and state or government are closely combined. That if you like, you can allow some fluidity. Often, we find it in a frontier area. If you take many cities, border cities in Europe, for instance, the population, they work, for instance. I forgot the name of the city, but people…

In Basel, for instance, it’s a typical case where people, there is a regulation where they pay taxes, but then they have the possibility of mobility. We need that kind of national liberation conceptualization and imagination that goes against any tough nation-state models. The idea that you need sovereignty is very important, whether in a two-state solution or in a one-state solution.

Talia Baroncelli

There was something very interesting you said at the beginning where you said you’re opposed to some forms of post-colonial studies. I know that some scholars have criticized various forms of post-colonial studies, saying that it puts them in a box that the only way they can respond is within those same colonial terms that European colonizers imposed on them. The only way to get out of it is to use those same terms which categorize them according to certain hierarchies. I’m just wondering if your criticism is along those lines or why you would perhaps be opposed to certain strains of post-colonial studies.

Sari Hanafi

Thank you. This is a very good question. Look, first of all, I am not against post-colonial theory. I think the remnants of this division of labor in knowledge production, in academia, in media, are still to a certain extent influencing how people look to the ‘other.’ How the orient is constructed, imagined, et cetera.

However, I am criticizing post-colonial discourse. What I saw during the Arab Spring were people who supported an authoritarian regime like a Syrian regime because it’s allying with a resistance movement like Hezbollah. Something they don’t want to see that is very important for the population is not only are they resisting imperialism, but resisting authoritarianism, which has its own internal dynamics.

This post-colonial discourse has two features. The first one is focusing too much on imperialism without seeing the emerging empires. Iran has empires. Turkey has empires. The United Emirates and Saudi Arabia have empires. These are local, but they play a role in supporting elite formations, supporting the regime, supporting repression, and so on. This is one feature.

The second is sometimes the discourse creates this ‘us’ and ‘them,’ the West versus us. I think this dichotomy is not always useful or as simple as that. I don’t want, in the name of post-colonial theory, to replace French sociology with Arab sociology. It’s not like this.

I see that today, in order to understand my social reality, how I can use Marx and Ibn Khaldun to complement each other in order to understand the political system or political economy. It’s not to say either Ibn Khaldun or the other.

Today, for instance, with my students, we had a major debate about the universality of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. They want, because they see the Euro-American reaction supporting genocide in Israel, they wanted to throw the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at them. What I claimed today is how we can disentangle this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a very important document produced through a consensus where everyone participated, including the Rapporteur Charles Malik, who used to have this office where I am now. It is my office. How to disentangle this beautiful document from the Western power as a guardian or Western referentiality or guardian of this document.

Today, if you ask me who the guardian of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights is, it is not France, Germany, or the United States. It’s Gambia who thought about Rohingya. It’s South Africa that thinks about Palestinians. It’s Chile and Nicaragua. It’s very interesting. It’s Latin America and Africa who are now the custodians of the universality of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This is where I introduce this nuance. To say, you don’t understand todays academics: knowledge, and production; if you don’t implement the post-colonial approach by anti-authoritarian approach, how there are local elite who become so authoritarian, disconnected, whether the colonial power support them or not they are playing an important role, for instance, in knowledge production.

I see in the Arab world how our universities are full of censors and self-censorship. People are afraid to talk about many, many issues. Do you expect there to be political sociology in Egypt? Is it because of the post-colonial studies or because of the authoritarianism in this country? This is how I try to problematize how we used and abused post-colonial studies.

Talia Baroncelli

Right. I think perhaps one of the largest aims of imperialism is to create categories and then to divide people along those lines. There’s a great effort, and many scholars, post-colonial scholars, have identified the European colonial roots of the current legal system that we have. If you just stop there, then you’ve succeeded in perhaps deconstructing something, but you’re not presenting an alternative which other people, other scholars, perhaps Marxist scholars, would say lies in taking Marx’s work and infusing it with some of the other writers or political scientists that exist right now to fuse it together to have this critique of elite structures and to show how the law is also used and those standards are weaponized by imperial powers, but those very laws can also be to bring about a certain form of equality. As you say, Gambia, Nicaragua, using those standards to turn it on the Western imperialists and on this form of hegemony.

As you said, it’s inaccurate or perhaps misplaced to throw the baby out with the bathwater, and we need this multifaceted approach to these studies.

Sari Hanafi

Exactly.

Talia Baroncelli

Not just focusing on this specific history of colonialism, but also trying to understand the capital relations that actually drive it and which seek to continue this dividing or tensions between groups and to give them the impression that the only way that they can fight a certain struggle is to be even more entrenched in their very narrow positions, which is perhaps what imperial powers actually want. I think it’s important to try to go against that and to fuse different perspectives and not to say one or the other, but to unify all of them and to have a universality that enables solidarity.

Sari Hanafi

Exactly.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, Dr. Sari Hanafi, it was really great speaking to you. Thank you for taking so much time to join me today. It was really great.

Sari Hanafi

Thank you. It was a pleasure.

Talia Baroncelli

Thank you for watching theAnalysis.news and for expressing your interest. If you’d like to support us, please visit our website, theAnalysis.news. Thanks for watching.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Sari Hanafi is currently a professor of sociology at the American University of Beirut and chair of the Islamic Studies program. He is the president of the International Sociological Association and also the editor of Idafat: the Arab Journal of Sociology.