As a Socialist, I have No Voice in the Mainstream – Chris Hedges on RAI (6/7)

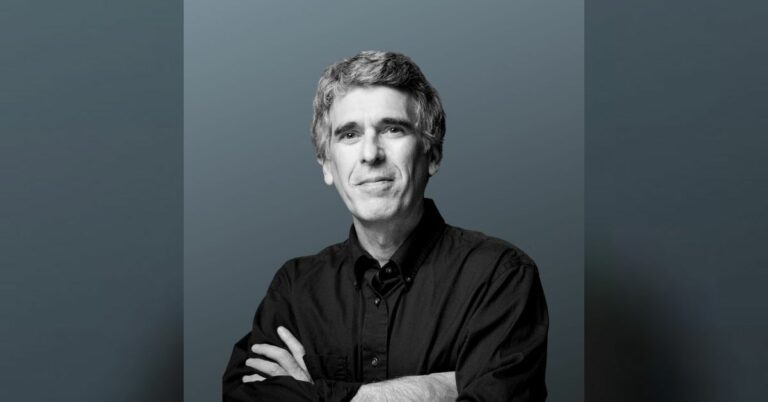

On Reality Asserts Itself with Paul Jay, Chris Hedges says an effective movement that defies power will have to be disciplined and articulate what a vision of socialism might look like. This episode was produced on July 24, 2013.

TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And welcome to Reality Asserts Itself.

We’re continuing our series of interviews with Chris Hedges. And if you haven’t seen the other parts, I suggest you go back and watch from part one forward, ’cause then this will all make more sense. But if you don’t want to, it will probably still make some sense.

Now joining us again in the studio in Baltimore is Chris Hedges. He’s a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, a senior fellow at the Nation Institute, and he writes a regular column at Truthdig.

Thanks again.

CHRIS HEDGES, JOURNALIST AND WRITER: Thank you.

JAY: So people watching this, what would you suggest they do next?

HEDGES: We have to begin to build organizations to protect ourselves from corporate forces that are determined to exploit the ecosystem until it collapses. We have to recognize that the implantation of global capitalism is one that will reconfigure the world into a kind of neo-feudal society where workers here will be told that they have to be competitive with the sweatshop workers in Bangladesh who make $0.22 an hour prison labor in China. That’s already happening. We have to recognize that–the vast corporate systems that we have set up.

For instance, our food system is very fragile and is not sustainable. Food must once again be local. We can’t continue to feed ourselves on a system where we’re shipping all of our fruits and vegetables from California or Florida across the country. That means beginning to–and more than community gardens, but essentially buying local, creating sustainable systems that are local, because when things go down, the elites will withdraw into their gated compounds, where they will have access to security, water, medical facilities, all sorts of things that they will deny to the rest of us. They’re not going to take care of us when things come, when things go bad. And we have to begin to prepare for that.

It’s not a very pleasant scenario. It’s not pleasant to think about. But it’s survivable if we begin to respond to what’s coming. As long as we remain unplugged, as long as we are checked out, which is how they want us, we’re going to be left defenseless.

JAY: Some of what you’ve suggested people are doing. I mean, there are organizations trying to speak about the environment. There’s organizations speaking about housing and unemployment and this and that, and so people still left wondering, what can I do that would make a difference to this, ’cause the current kind of left politics, while there’s breakthroughs in certain places–you talked about Chicago teachers, and there’s–you know, there was the rebellion in Wisconsin–rebellion–big protest in Wisconsin. You know, things happen. And across the country there’s many more things happened than we know about. And we tried to cover some of this on The Real News. We don’t really have the capacity to cover all that’s happening. And I think because it’s not getting enough coverage in, certainly, the mainstream media, people think nothing’s happening. And, in fact, more is than a lot of us think is, but not at the scale, you know, that would make the kind of changes that, you know, you’re suggesting we need. So people are still left with, like, what’s the key link for what’s next.

HEDGES: Well, the more we create self-sustainable systems that are local, the more we sever ourselves from these corporate forces, the less we need them. And the less we need them–I mean, let’s remember that 70 percent of the U.S. economy is driven through consumption–the less we need them, the more we impoverish them. I mean, the goal has to be to break these corporate power, this entity that has seized control of our government, our systems of communication, our judiciary.

I mean, now we’re watching them eviscerate our systems of education. Anytime hedge fund managers walk into a city like Baltimore and propose charter schools, it’s not because they want to teach people to read and write. It’s because they know the federal government spends about $600 billion a year on education, and they want it, and they’re getting it.

So I think that building local centers that are self-sustaining and that can create forms of community that are not dependent on these corporate forces is a political act, because these corporate forces need us to continue to consume their products and rely on their services. And the less we consume and the less we are hostage, the less we need these forces, the more independent we become.

Now, that has to come with a kind of political consciousness, but I think they come hand-in-hand, that both things–I think that as people take control, once again, of their own lives, that will bring a kind of consciousness, because these corporate forces, especially if they begin to feel threatened, are going to see these acts as political acts and are going to move–as we have seen corporate farming move against organic farming, they are going to move to try and destroy these forces.

JAY: One of the things I don’t think the left talks about very much in the United States and Canada, and maybe in many countries for different reasons, they don’t often talk about who owns stuff. There’s a lot of talk about lack of fair distribution, there’s a lot of talk about the power of the state, and all rightly so. But who owns stuff doesn’t get talked about that much.

And in the piece you wrote, in terms of you said this gravest mistake is not articulating a vision of what a democratic socialism might look like, and you talk about nationalizing the energy companies and other kinds of things like that, is part of what’s missing is that doesn’t seem to be part of the left discourse in any kind of unified way? Like, you have a big protest, there’s, like, 30 different things get talked about in terms of demands and issues. I mean, what got the Brazilian thing going recently was very specific. It was bus fares. And in Quebec it was tuitions. And here it’s like there’s always, like, 30 things, and then you have a debate about why isn’t it more focused, and it becomes a virtue not to be focused.

HEDGES: Well, because, you know, as somebody who identifies himself as a socialist, I have no voice in the mainstream. You’re not going to hear my voice. To even call yourself a socialist in this country is to essentially remove yourself from the acceptable parameters of public discourse.

JAY: Including in the movement.

HEDGES: The movement is so fractious and the movement is so diffuse that–I mean, I think–let’s go back to the Occupy movement. I think a lot of that is–I look at it as a very kind of new, green, maybe even immature expression, but it’s a beginning. You know, if we are going to build effective social and political movements that defy power, they’re going to have to do a lot of things that were not done in Occupy, like become very disciplined and focused and delineate between what is right and wrong.

I mean, part of the Occupy movement is they had that kind of bourgeois liberal notion of tolerance. You know, everything is okay. Well, everything isn’t okay. You know, if we’re going to build a political force that is going to counter systems of power that seek to destroy us, you know, some things are not acceptable and some things are acceptable.

And I think many of the Occupy activists–you know, and I was associated with the Wall Street movement in Zuccotti–really came to that understanding. I mean, they lost control of the park and the individual tents went up. The, you know, activists were spending all night in de-escalation teams to stop fights [incompr.] drugs came in. The cops were dropping off homeless people. They were taking people out of Rikers and dropping off, and because they knew that they could overload the system to destroy it. And they did, coupled with all the infiltrations and surveillance and everything else.

So we’re just beginning. And I think part of that is a political maturation that begins to articulate what it is that we want. And, you know, at least they know what they don’t want. They don’t want ExxonMobil determining our children’s relationship to the environment. But that really means that we have to destroy ExxonMobil.

JAY: You’ve got to change who own stuff.

HEDGES: Well, you have to nationalize. You have to build an energy system that is responsive to the needs of the citizenry, not to a corporate board which is awash in tens if not hundreds of millions of personal wealth. I mean, and so I think that’s coming and I think those questions are being asked.

I think we’re in this kind of strange period when the language we use to describe our economic and political system no longer matches the reality. I mean, laissez-faire capitalism–we don’t live in a system of laissez-faire capitalism when the federal government bails out these institutions to the tunes of trillions of dollars and then keeps pumping out free money from the Fed and handing it to–that’s not laissez-faire capitalism. And yet I’m sure that if you went to Wharton or Harvard Business School, they would still be teaching this fictional system. And we haven’t yet moved into a period where the vocabulary we use to describe our reality matches that reality. And that’s always a revolutionary period, because there’s a disconnect between the way we speak about ourselves and the way we actually function. And that’s where we are. And so we in many ways are searching for the words to describe what’s happening to us and then to articulate another vision of where we want to go. And we haven’t gotten there yet.

JAY: I may be well proved wrong on this, but I think the emperor-has-no-clothes moment is that I think the older of us who grew up with in the Cold War and have all the memories of all this, we’re way more hung up on the word socialism than young people are. I don’t think they’re very hung up on it. And there was a really interesting moment in the 2008 elections. In the last couple of weeks, when Obama’s starting to pull away, McCain pulls out he’s a socialist, you’re a socialist, you’re socialist, and that was going to be the thing to scare everybody. And it’s the one thing I thought Obama hit a great note. I don’t think he believed it, but he hit a great note. When he was accused–he’s asked, are you a socialist, he said, well my Bible teaches me I am my brother’s keeper, and the whole thing went away. And there was a magazine–we’re all socialists now. And there were surveys. Young people don’t care. They’re not worried about the term. I mean, one of the great achievements, I thought, of Occupy was you could actually talk about capitalism is a system. But then you also got to talk about an alternative.

HEDGES: Right. I think Occupy was getting there. You know, Occupy was–I like to think of it as tactic, not a movement, in the same way that, you know, Rosa Parks gets on the bus and it’s five years before the Freedom Riders get on their bus. I look at Occupy like that, that what comes next, something will come. It will build on what came before. It will begin to answer questions that weren’t answered before.

JAY: And I’m guessing it’s going to happen in a few key cities.

HEDGES: Probably, yeah. I think that’s right. But where and when–I mean, having covered movements, you can never tell. You can sense that it’s in the air, but what triggers it, what it looks like–. And, when I covered the street demonstrations that brought down Milosevic, I was spending time as a New York Times reporter with the purported leaders Dindic and Draskovic, but in fact they were struggling to figure out what the crowds wanted, that it had a kind of life force of its own. And it was really interesting being around them as much as I was, because most of the time they were trying to take the pulse of the public.

JAY: I was just talking to a friend of mine who has friends that organized the transit fare protest in Brazil, and they were as shocked as anybody that this became this national movement. They thought they had this little local transit fare protest going.

HEDGES: Well, you know, the PLR covered the first intifada, and the PLO, which then was in exile in Tunis, had nothing–was as surprised as the Israelis. And while they, you know, struggled to sort of take charge of the movement, again, they spent most of their time trying to figure out where the people on the street were going.

And that’s how movements work. And, you know, the best leaders in uprisings can read, can read the pulse. But that’s what they’re doing. That’s how it will happen. And when it happens, where it happens, what it–no one knows.

JAY: Okay. In the next and final part of the interview, we’re going to ask viewer questions. So join us for the next part of our interview series with Chris Hedges on The Real News Network.

END

Podcast: Play in new window | Download