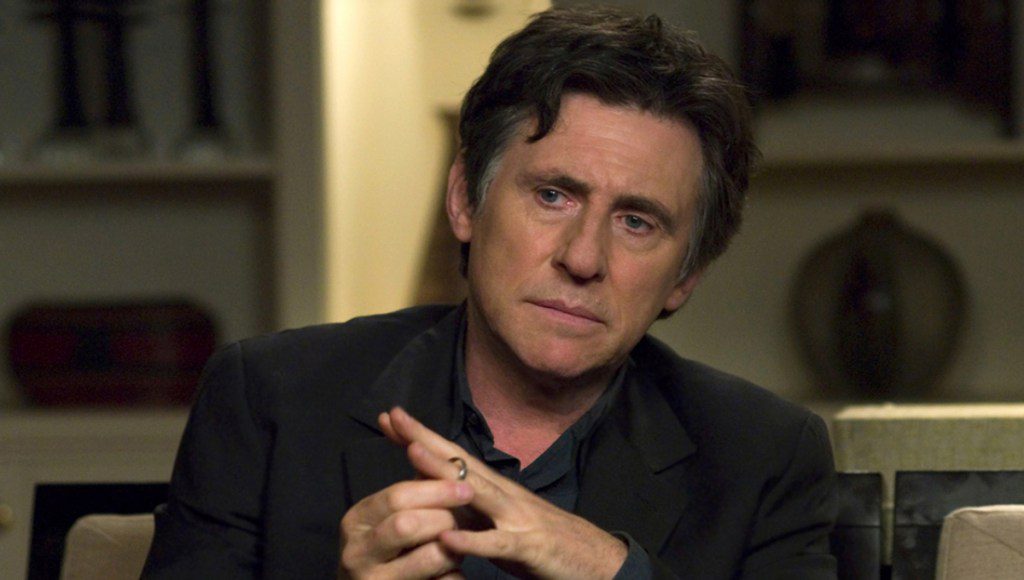

From Priesthood to Actor to Activist – Gabriel Byrne on RAI Pt 1/4

On Reality Asserts Itself, actor and climate activist Gabriel Byrne speaks of growing up in a working-class family that was religious, Irish nationalist, and where joining a seminary made parents proud. He came to understand the injustice of the life working men like his father faced; with host Paul Jay. This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced December 22, 2017.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

Paul Jay: Welcome to Reality Asserts Itself on the Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay. Gabriel Byrne is an Irish actor, film director and film producer, a writer, and was named Ireland’s first cultural ambassador. Gabriel has appeared in over 35 films such as Excalibur, Miller’s Crossing, Little Women, the Usual Suspects, Stigmata, End of Days, and the 33. He starred in the recent HBO series In Treatment. He co-wrote the 1996 film The Last of the High Kings. He’s also produced films like In The Name Of The Father, which was nominated for six Academy Awards. He was also the subject of the documentary Stories From Home.

He’s also a passionate advocate for accepting the reality of the existential crisis of climate change. He fights to find effective solutions. Gabriel Byrne now joins us in the studio. Thanks for joining us.

Gabriel Byrne: You’re welcome.

Paul Jay: On Reality Asserts Itself, as most of the Real News audience knows, we start with your personal backstory and then we get in to what you think about stuff. For full disclosure, Gabriel watches the Real News. He’s donated a few times. We’re friendly here but I’ll see if I can’t give him a bit of a hard time.

Paul Jay: You grew up in a working-class family in Ireland. You once said, “Give me a kid until he’s seven years old and whether it’s the church or some Americanism or fascism, give me a kid until he’s seven and I’ve got him forever.” Well, the Catholic Church and Catholicism had you until you were seven. Irish nationalism, which is intertwined in Catholicism had you until you were seven. They didn’t have you forever.

Paul Jay: Talk a bit about the internalizing of the religion and growing up with such religious thought to the point that at 11 years old you go off to a seminary on track to be a priest. Talk about that part of your life and then we’ll get into how you break with them.

Gabriel Byrne: Well, I wasn’t the one who said give me a child until he’s seven and he’s [crosstalk 00:03:12]

Paul Jay: You’re quoting someone?

Gabriel Byrne: Yes. It was the Jesuits I think who came up with that one and how right they are about that because of course a child doesn’t have the ability to reason. That’s why they say when you get to the age of seven that is you have reached the age of reason. Up until that time it’s a form of inculcation and brainwashing, whatever you want to call it. Laid down in the teaching in those years is a notion of heaven and hell and the idea of consequences for action but also for thought.

Gabriel Byrne: You could go to hell for committing an infringement against one’s parents or the school or whatever. I remember once in a class a teacher trying to relay to us the horrors of hell and the consequence of bad action. He took a kid from the front row and he struck a box of matches. He held a lighted match under the kid’s finger until the kid obviously grotesquely danced away in pain. The teacher said, “This is what hellfire is like except that your entire body will be on fire. It will be for eternity.”

Gabriel Byrne: He then went on to explain to us what the notion of eternity was and to us at a very young age he made us repeat again and again and again the word forever. Forever, forever, forever, forever until the word made no sense. You knew that there was this place of horror.

Paul Jay: Was he a priest?

Gabriel Byrne: No. He was a teacher. Also, on the other side there was the notion of reward for good behavior, which was heaven. Fear was laid down very early on in the way that you saw the world. Fear was a great way to make you conform. Corporal punishment was endemic to the system. We were beaten regularly for all kinds of supposed misdeeds. Cruelty and corporal punishment went together.

Gabriel Byrne: In a religious institution like the one that I was taught in at the beginning you had these celibate men and women who had total and utter authority over you. In many cases, they were extremely unhappy people who were forced into this condition of celibacy and were in charge of children.

Paul Jay: How pervasive was sexual abuse in the school?

Gabriel Byrne: You know, in the early years I don’t think anybody was aware of it. There were rumors here and there about people. We were too young to know what that actually meant. As we got older, of course, the rumors began to be more prolific. I think the full horror of it didn’t come out until we were adults and we looked back and thought, “Oh my God. That was part of what the system was.”

Gabriel Byrne: You made a good point there that nationalism and Catholicism were intertwined and that’s true. The way we learned history was interesting. We learned it from an emotional point of view. Our enemy was England. Everything about England was nefarious and evil. We were very proud of the fact that we resisted the British conquest for 500 years. At the same time, we had a kind of victim approach to history. That we were the victims of this appalling country that took it out on us for no reason whatsoever.

Paul Jay: How much of your personal identity was your national identity?

Gabriel Byrne: Well, the internalizing of Irish history was an emotional experience. There was in the teaching of history an emotional element to it. This was a country where heroes were people who died for the country. That was a thing that was among many people aspired to the idea of being a martyr for your country. Those people were venerated.

Gabriel Byrne: Catholicism was unquestioned. Nationalism, to a great extent, was unquestioned. You internalized those things before you had the time to really think about them. When I came to 11 years of age it didn’t seem … Although it does now of course. It didn’t seem strange to me to decide at 11 years of age that I would want to become a priest.

Paul Jay: In spite of the corporal punishment.

Gabriel Byrne: In spite of all that. Yes, in spite of all that.

Paul Jay: What were you getting at home? What did your parents do? Had they bought into all this themselves? Did they challenge any of this in any way?

Gabriel Byrne: To say bought into it implies that in some way …

Paul Jay: Yeah. It’s the wrong word bought in. They were immersed in the same culture.

Gabriel Byrne: It was cultural. It was social and cultural. The Irish word for church is ‘teach an phobail,’ which means the house of the people. It was cultural and social as much as it was religion. The idea of a God and heaven and hell were accepted without question.

Paul Jay: There was a left in Ireland at the time, which was nationalist but not necessarily so religious, wasn’t there? Or secular?

Gabriel Byrne: I certainly didn’t grow up with a sense of there being an oppositional force to it or there being a left perspective. We used to pray, I remember, for the conversion of Red Russia. The teacher would stand up at the end and say, “Now we’ll say a prayer for the conversion of Red Russia.” We also had our own kind of colonialism but we didn’t see it as that.

Gabriel Byrne: Ireland never invaded anywhere but we would send out these missionaries to countries to convert them to Catholicism because they were godless and had no direction in their lives so they needed to be saved. That movement was supported by us at home in the form of putting pennies into a little box. There was a little black boy who would nod his head every time you put in the coin. That was for the conversion of their souls.

Gabriel Byrne: The emotional nationalism that I grew up with and later came to see that we weren’t exclusively the victims of Britain but we were actually part of the colonial empire and that other nations also suffered like we did. I can remember my mother telling me that her grandmother saw people starving by the roadside in the Irish famine in 1845 where the population of the country went from 8 million to four in the space of four years, which precipitated the huge immigration into America and Australia from Ireland. It had a profound effect not just on Irish history but on American history too.

Gabriel Byrne: That was a huge psychic wound in the Irish soul. People remembered it and they remembered injustice and they remembered the rising of 1916. When I went to England when I was in my twenties to become an actor I had the real sense for the first time of the fact that I was Irish. I didn’t ever question my identity, my Catholicism really until I went to England.

Paul Jay: At 11 years old you go to a seminary that’s in London?

Gabriel Byrne: That was in England. Yeah.

Paul Jay: Any doubts? Or you are a full true believer still at 11? Let me add, some of the abuse that happened in the school you were affected by. At 11, you’re still headed towards being a priest.

Gabriel Byrne: Yeah. I think that when you are … I don’t want to use the word brainwashed but certainly when you are inculcated about certain notions about the way the world operates it’s not that I sat down and said, “Hmm, I wonder should I …” It seemed like a natural extension of the life, the society that I lived in.

Paul Jay: There were a lot of people … Not a lot. The vast majority of people that grew up in that culture don’t become priests.

Gabriel Byrne: True.

Paul Jay: They may go to church, they may be true believers, but they don’t pick the path of that.

Gabriel Byrne: True.

Paul Jay: Did that get partly inspired from your family or your own internal thing, “I want to be a priest”?

Gabriel Byrne: If you look at the way a church presents its rituals it’s very deliberate. You have a stage, which is the altar. You have the leading actor, which is the priest. You have stained glass, which produces a certain effect.

Paul Jay: It’s all theater.

Gabriel Byrne: It’s all theater. Incense, which is a sophomoric effect.

Paul Jay: Even this enormous church with all the overpowering architecture.

Gabriel Byrne: Absolutely. Absolutely. I was just noticing that when I came into Baltimore yesterday.

Paul Jay: A lot of churches.

Gabriel Byrne: A lot of churches here.

Paul Jay: This Baltimore was the Catholic city versus New York.

Gabriel Byrne: Yes. The prominence of that architecture in the community. Every village and every town in Ireland has a church. I became an altar boy and the congregation, the audience, it was all very similar. I think there must have been something in me that was attracted to that even though I’m an extremely shy person and was then crippled with shyness. Yet, I had this compulsion to be doing that. I don’t know why or how that manifested itself.

Paul Jay: What is your internal conversation with God at this time? You’re praying? It’s a real thing in your mind?

Gabriel Byrne: Well, it was a personalized God. The idea of it being a force or an invisible spirit it wasn’t that. It was actually a physical person in a physical place so that when you thought of God you thought of an old man with a white beard. In fact, there was a guy who used to live on the street next to us who had a white beard. His nickname was Holy God. That image of God, that personal image of God, and the reality of a place called heaven to a child was deeply reassuring because I think that one of the powerful things that religion gives is a sense of reassurance and security and that the answers to extremely complex questions are in many cases simply laid out.

Gabriel Byrne: My relationship to God at that time was a child’s relationship. The religion itself had the magnetism for me of a fairytale. There’s an element of the fairytale in the religion anyway. The greatest gift that could be bestowed on an Irish-Catholic household was to have a priest in the family. There are families where there are priests and nuns and several … Not anymore because vocations have fallen off hugely.

Paul Jay: It would have made your family proud?

Gabriel Byrne: Very proud. Yeah. I thought in my child’s way that it gave me tremendous reassurance that there was somebody up there, a powerful paternal figure who was taking care of me, and that I could talk to in the form of prayer and that I could try and live a good life with his help.

Paul Jay: What did your father and mother do?

Gabriel Byrne: My father was a laborer. He worked in Guinness’ brewery, the famous Irish brewery. He was made redundant at 50 years of age. I remember thinking to myself at the time, somewhat cruelly but at the same time in a childish way, “Well, he’s so old anyway. He’s 50. What does he care about going to work?”

Gabriel Byrne: It’s only later I reflected on the absolute injustice of what happened to him and people like him in that their identity as working-class men was bound up in the work that they did. When they got to be 50 they were just thrown on the scrap heap. They got a pension. A small pension but their worth as human beings plummeted to the point where I’m sure they had appalling days and nights of suffering because they were no longer the breadwinner.

Gabriel Byrne: My father used to come in on Friday evening with a little brown envelope and he would put it behind the mirror and my mother would take it out and give him back his money for his drink and his cigarettes and tobacco, whatever. That was no longer the case. The roles became reversed and my mother went out to work.

Paul Jay: What did she do?

Gabriel Byrne: She was a nurse. She worked the night shift and my father took care of six of us during the daytime. I remember my father, that sense of … Associated with unemployment was this notion of shame. That somehow it was your fault. I knew he carried … I couldn’t articulate it really at the time. I knew he carried an invisible hump on his back, this sense of failure, and shame. He tried to do other jobs. Nobody would employ him. He died at a relatively young age. I think a great deal of that had to do with the fact …

Paul Jay: How old was he?

Gabriel Byrne: He was 66.

Paul Jay: About where you are now.

Gabriel Byrne: Yeah. He believed all his life. He went to Mass every single morning.

Paul Jay: How much did you share your internal life with either of your parents? Especially when you started having some doubts about the path you were on.

Gabriel Byrne: I think the culture of the time … I’m not sure what it was like here. In Ireland the idea that parents and children would sit down to discuss an internal life was kind of … I remember there was an American television series that was beamed into us in Ireland ludicrously opposite to the experience that we had. It was called The Brady Bunch. I don’t know if you remember it.

Paul Jay: Sure.

Gabriel Byrne: We used to look at this. We’d all be sitting around in the sitting room on two or three chairs. I don’t want to make a Frank McCourt situation but it wasn’t luxurious. We’d be watching this thing called The Brady Bunch and they had a maid who poured orange juice for them before they went to school. The father would say, “Okay, kids. Let’s have a meeting.” I would look at this and I’d say, “This thing isn’t funny. Why is everybody laughing at this thing?”

Gabriel Byrne: These kids were saying things like, “Oh, yeah. I have a crush on this girl at school.” Kids went to mixed schools, for a start. They were able to say to their parents, “I had a crush on this …” They were incredibly happy because they had everything. It looked to me like an unattainable ideal. What was really being shown there was to a certain extent the American Dream. The American Dream clashed with Dublin working class reality. You just looked at this thing and you said, “My God. There are people who live like that? That’s what America is. Everybody in America lives like that.”

Paul Jay: You mentioned in school you would pray for the conversions of the Red Russians. This is you’re growing up during Cold War years and both the American/Russian rivalry, the potential of nuclear war. Certainly in this country relentless propaganda against anything left, anything secular, anything that is even quasi-socialist, never mind communist, and a purge of the left in many state institutions and Hollywood and such. How much is that Cold War ideology part of what you grew up with?

Gabriel Byrne: I remember the incident at the Bay of Pigs and the world being brought to the edge of nuclear war. Suddenly the world started to get really small because we lived in Ireland and that was the world to us. Suddenly there was the possibility of annihilation because these two people were doing what? They were having some kind of a row.

Gabriel Byrne: I remember watching this in … They used to put television sets in windows of shops. We were all gathered around this window watching some kind of a discussion or a program about Kennedy and Khrushchev. I didn’t understand it at the time. I was looking in the window and this guy was saying, “Well, that guy is Khrushchev. That guy, Kennedy, is the good guy. This guy is the bad guy. Kennedy is going to stand up to him. If they attack America the entire world is going to be blown up and set on fire.”

Paul Jay: You’re about 13 or 14.

Gabriel Byrne: Yeah. Suddenly the world became a very terrifying place. Kennedy was deified in Ireland because of course he had Irish-American roots. There used to be in Ireland a very common thing, which was a picture of the Pope looking one way and Kennedy looking the other way. Sometimes Jacqueline Kennedy-Onassis, until she married Onassis. Then she was taken out. The Pope and Kennedy were the two earthly gods. Kennedy could do no wrong.

Gabriel Byrne: In fact, he came to Ireland to visit about six months before he was assassinated. They talked about him in the sense of, “Our boy has come home. The Irish grandfather who left Wexford with nothing and then achieved the American Dream and his grandson became President” and all that stuff. I think after that I was never as secure about the world. That went really deep.

Paul Jay: In the next segment in the interview we’re going to explore Gabriel’s next phase as he starts to break with some of the both nationalist and Catholic religion that he grew up with. I don’t know if I’m overstating it but coming to a political consciousness that starts to question and challenge many of those assumptions. Please join us for the next segment of our interview with Gabriel Byrne on Reality Asserts Itself.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download