“I Can’t Breathe” – Gerald Horne on Reality Asserts Itself (pt 6/6)

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on August 25, 2014. Mr. Horne says these words are this enormous metaphor for the black condition in North America stretching back centuries, the suffocation, the cry of despair, the cry of horror.

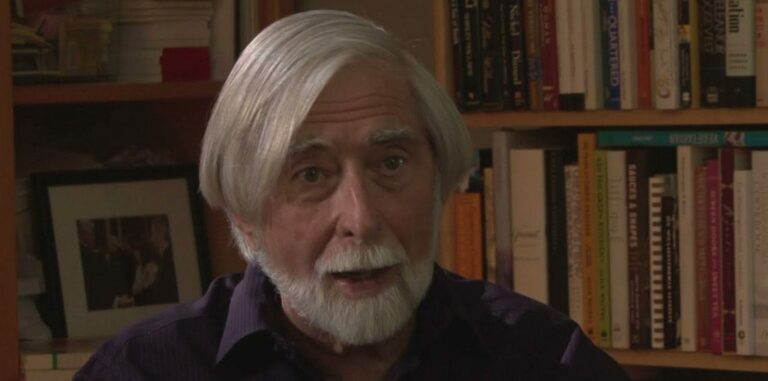

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself.

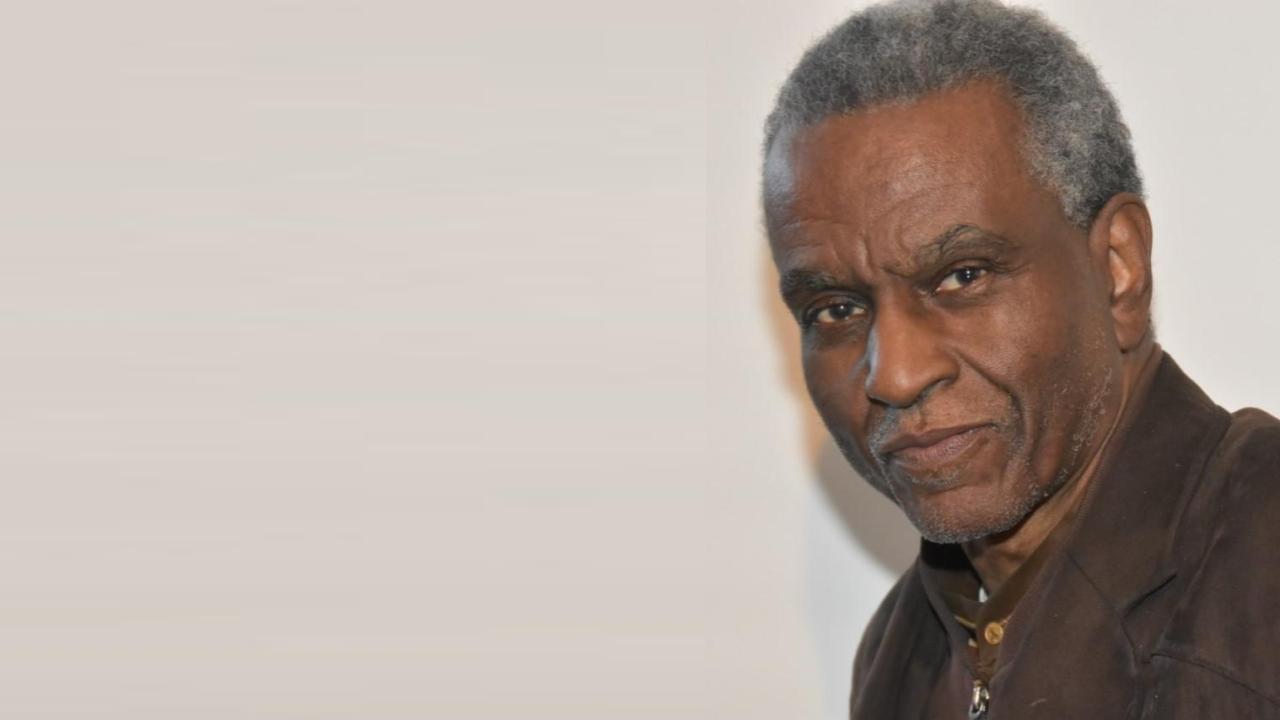

We’re continuing our series of discussions with Gerald Horne, who now joins us in the studio. Gerald’s recent book: The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America. And he’s the author of about 30 other books.

Thanks for joining us again.

GERALD HORNE, HISTORIAN AND AUTHOR: Thank you.

…

JAY: Thanks for joining us.

HORNE: Thank you.

JAY: So, in the Civil War, as we talked about in the last segment and we touched on, this slave system and the power of the slaveowners was getting in the way of this exploding industrial capitalism in the Northeast at all kinds of levels. But it seems the Northerners, Northern capitalists, are [in] a little bit contradictory position, in the sense that this whiteness is pretty good as an ideology, ’cause if you can focus white workers on black workers, it’s a good distraction, because the class contradictions were getting pretty fierce at the time with white workers in the North. On the other hand, you’ve got to sell white workers on going to fight in the South, and one of the big stated objectives, at the very least, is the abolition of slavery. So you have abolitionists and others quite strongly saying, no, these people are humans. It’s somewhat a contradictory message.

HORNE: Mhm. Well, yes. There are so many contradictions, I don’t even know where to start. I mean, first of all, it reminds me of Cuba during the slavery period, where on the one hand you had this one group of U.S. nationals who were making money hand-over-fist going into the Congo River Basin, snatching Africans, and bringing them to Cuba to be enslaved, and working on plantations often owned by U.S. nationals. Then you had another group of U.S. nationals who were complaining about a process and a term that I guess is fortunate has disappeared from the language, the English language, which is Africanization. That is to say, they were bringing so many Africans to Cuba, there was a fear that conditions were being created that would allow for another Haiti, that is to say, a slave rebellion, not least because of ratios that would lead to not only a Haiti on the doorstep of Florida, but another kind of Haiti, in the sense of Cuba, being on the doorstep of Florida. So that’s a contradiction.

Then there’s contradictions about capital itself. That is to say that, as noted, there were individuals in Baltimore and in New York and Boston who were profiting quite handsomely from the slave trade. There were other individuals who felt that diverting so much capital into slavery was ultimately inimical to the wider and larger interests of the United States, because it was felt that capital could be more profitably diverted into manufacturing, for example. And as noted, you had slaves working in manufacturing plants, but that was not seen as optimal, given the spinoffs from capitalism, that is to say, workers being able to have multiplier effects by buying clothes, buying foods, buying housing, etc., which from the capitalist point of view was something of a virtuous circle, leading to the upward rise of the enterprise.

But it’s striking to note that even after the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was enacted in the 1860s, after the U.S. Civil War, which basically frees the enslaved, after the abolition of slavery with the Emancipation Proclamation, you still have U.S. nationals who are involved in the slave trade, not only to Cuba, where slavery doesn’t end until the 1880s, or to Brazil, where slavery doesn’t end till the 1880s, but you still have the process of kidnapping. Even after the U.S. Civil War, you have black Americans, U.S. nationals, being kidnapped from the streets of Baltimore. Next thing you know, they’re working in the fields of Cuba, or perhaps even in the fields of Brazil. Not only that, but as I state in an earlier book that I published entitled The White Pacific, you had slave dealers from the United States who, after the U.S. Civil War, Migrated to the South Seas and began kidnapping Melanesians and Polynesians and converting them into bonded labor in Queensland, Australia, and in Fiji. And, indeed, the then independent Kingdom of Hawaii objects and tries to block this trade, ’cause they’re also kidnapping indigenous Hawaiians, and for its pain and troubles, its regime is overthrown by the U.S. in the 1890s, leading to Hawaii becoming a state and the home of the first black president, becoming a state in 1959.

So this whole area that we’re talking about is just replete in contradictions.

JAY: Okay. One of the things that came up in the first segment that I promised we’d pick up on and before we kind of jump to today, this sort of one–another historical point, is the role of Japan.

HORNE: Ah, yes!

JAY: And in the leadup–in World War II, Japan positions itself as the leader of the fight against white supremacy in the world.

HORNE: Yes. I confess sheepishly it’s one of my favorite subjects. And I did a book some years ago on the Pacific War with that as a centerpiece. And I’m working on another book, ’cause I can’t get enough of it.

To start where I just left off, the Kingdom of Hawaii was trying to broker an alliance with Tokyo, which is probably why you thought of it at this point. That’s why so many of the Asian Americans in Honolulu are Japanese-American. This was part of a diplomatic alliance, which of course outraged Washington, ’cause they could already see over the horizon to see the Pacific War erupting a scant 40, 50 years later, in 1941-42. That also helps to fuel the overthrow of the Hawaii Kingdom in the 1890s.

But it’s interesting that Japan, which you may know was something of a hermit kingdom, not unlike how Korea has been described, up until the 1850s, when the black ships from the United States sailed into Japan and Japan, or at least the Japanese elites, faced the prospect of falling victim to what had occurred in neighboring Hong Kong in 1841, when the British had taken over–they were facing the prospect of being colonized. So you have this miraculous turnaround. So by 1868, with the Meiji Restoration, Japan is well on its way to becoming a major industrialized nation and a major imperialist nation, as evidenced by its attack on China in 1890s, which, of course, the Chinese have not forgotten to this very day. But in terms of positioning itself for global leadership, Tokyo felt that it could [still a march (?)] on the United States by making these pointed appeals to black Americans. I don’t know if they had learned or studied the lessons of other previous antagonists of the United States of America who had also made appeals to black Americans.

But in any case it’s quite striking that if you look at black American leadership in the period before World War II, W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus Garvey, Booker T. Washington, they all had contradictions between and amongst themselves, but to a greater or a lesser degree they were all pro-Tokyo. And many of them visited Japan, such as W. E. B. Du Bois in the 1930s, where he was lionized to degree. And as I’m going to talk about in this next book that I’m working on, Tokyo had flooded the zone, had sent agents into black American communities, beginning in the 1920s. You had all of these so-called pro-Tokyo fronts. Indeed, if you look at the history of the organization now known as the Nation of Islam, which, of course, has a strong base right here in Baltimore, if you look at its origins, in many ways it starts off as a pro-Tokyo organization, like so many. It hasn’t fallen by the wayside like most of the rest of them. And indeed this concept that–I know you at this enterprise, you’re into conscious hip hop–if you look at this concept of the Asiatic black man, which the Nation of Islam used to tell and some of the so-called conscious hip hop elements today in 2014 tell, it comes out of that period of the 1930s when the U.S. Negroes were saying, we’re not African, we’re Asians. You know, this was part of this pro-Tokyo orientation. And then, of course, if you look at Malcolm X’s autobiography, in the middle of the autobiography he talks about when he’s about to be conscripted. He goes to the draft board and talks about how he’s pro-Tokyo. What he’s expressing is this widespread idea that Japan had helped to seed amongst black Americans that Japan was the champion of the colored races, that if Japan defeated the United States, the U.S. Negroes would get a better deal. And I argue–.

JAY: Not unlike Spanish Florida. Go on.

HORNE: Exactly. And I argue in a previous book and I plan to argue in this next book that this is part of the momentum that convinces the rulers in the United States that they need to do something about this problem, because it’s inimical to national security to have this dispossessed population in great numbers on your shores that could be easily appealed to by foreign antagonists. And so, therefore, you begin this agonizing retreat from Jim Crow, try to create a black middle class that have a stake in the system, to use that term that was so prevalent not so long ago, and so that they would not be so susceptible to these foreign appeals. And to a degree, that’s worked.

JAY: How has it worked? Talk about today. How has it worked?

HORNE: Well, it’s worked, because, you know, you have some–I mean, I’m in Baltimore, so I’m well aware of realities, but you do have a black middle class, to a degree, that feel they have a stake in the system. You have certain black millionaires, even a few billionaires, who feel they have a stake in the system, less susceptible to the blandishments of–.

JAY: Mostly black city council.

HORNE: Exactly, which is something new historically in the United States.

However, to return to where we began, I think that part of the problem that our leading organization, the NAACP, made when they ousted W. E. B. Du Bois in 1948 on Cold War grounds–that is to say that he was perceived as being pro-Moscow and the United States was moving towards anti-communism in a more aggressive fashion–there were many problems with that approach. But one of the problems is that if you look at the great span, the great scope of the history of Africans in North America from the 1600s up until today, I have argued and will continue to argue that there are two constants. Well, actually, one constant and one variable. The constant, which helps to explain progress, is unremitting struggle and resistance, organizing, disciplined organizing. That’s the constant. But as your quote suggested, human beings have to make history with the cloth at hand. And that leads to the variable. And the variable which helps to explain how the constant is going to succeed or not going to succeed is our ability to lengthen the battlefield, to forge alliances in the international community, to broker international alliances. And so when the NAACP turned aggressively towards anti-communism, they were turning aggressively towards a wholly domestic strategy, relying heavily upon the munificence of U.S. elites, the U.S. Supreme Court, the Congress, etc. But that has not been the warp and woof of our history. The warp and woof of our history is not just relying upon those domestic forces but relying on international forces. And that’s the major weakness, I would argue, of the black struggle today is sort of not only relying not upon these global forces, but a kind of myopia, not even keeping up with these sorts of struggles. We know that in the U.S. Congress as we speak there have been all these votes taken in favor of the Israeli aggression against Gaza. So I won’t single out the Congressional Black Caucus or black elected representatives, ’cause they share a lot of company in terms of not being heroic and speaking out, but certainly I think it is not unfair to suggest that black Americans above all should be speaking out against this kind of aggression, because our history has suggested to us that when there is that kind of injustice abroad, it inevitably strengthens our opponents here at home to our detriment. So it’s in our self-interest not just as an act of morality or an act of benevolence to speak out against these kinds of international outrages. But, alas, many of our elected representatives are not, and I think we’re suffering the consequences.

JAY: This emergence after the civil rights movement and, as you talked about, the various reasons for why it was in the interests of American elites to make these kinds of compromises, but with a great deal of success, a lot of the black elite in the United States has really adopted Americanism. And President Obama can talk about we’re all in the same boat and talk with nostalgia about 1776 and so on, and that stratum is kind of all there with him.

HORNE: Well, sure. But the die was cast when the decision, the fateful decision was made to throw in our lot wholly and exclusively on the domestic scene, to put all our eggs in that one basket. After you make that decision, well, there is a certain logic that unfolds and flows.

JAY: Well, King broke the silence.

HORNE: Sure.

JAY: He, I think, in certainly his last set of speeches did what you’re suggesting should have been done.

HORNE: Sure. But he was killed.

JAY: But he was killed.

HORNE: Right. And, you know, it’s interesting. I’ve given a number of interviews about the 1776 book. In one interview I gave, this journalist was asking me, do I think that this book should have gotten more publicity, given its thesis and the research, etc. I said, hey, look, in the United States, I’m happy to awake every morning without facing indictment or a murder plot against me. So, I mean–and I say that jokingly, but in a sense what it bespeaks is a sort of atmosphere in this country where you know that if you step out of line, you’re going to get slapped down. And getting slapped down is sort of a euphemism.

JAY: So we’re in Baltimore. And in, you know, ’68, ’69 there were tanks on the streets here.

HORNE: Mhm. I remember that.

JAY: There was a real outburst of resistance, both organized and spontaneous. Not so much now. We had our grand opening a little while–a few weeks ago, and we kind of talked about how in Baltimore there’s something like–I don’t know, somewhere–it depends on the year–230, 240, 250 murders every year,–

HORNE: Wow.

JAY: –of which, last year, 11 were white people and everyone else was black.

HORNE: Wow.

JAY: The chronic poverty here–I mean, it’s all kind of become a new, acceptable norm. How much does this ability of America to kind of accept mass incarceration rates, accept this Third World within the country, how deep is this in the culture and what we’ve been talking about, how this weighs on people’s minds from the past?

HORNE: Well, a couple of points that come to mind. One is that certain analysts are suggesting that black Americans are the most incarcerated, imprisoned population on this small planet. Certainly we disproportionately populate death row, which is rather chilling to contemplate. Walking over to your studio, I passed by all of these buses–Maryland Corrections. I assumed that prisoners were being transported into the courthouses.

JAY: Yeah, which are all right behind us.

HORNE: Exactly. Walking over here I passed a building that carries the name of Clarence Mitchell. The Mitchell family is a prominent family, a black family in the city of Baltimore. And Clarence Mitchell, who was a lobbyist for the NAACP for years, one of his close relatives, Parren Mitchell, was a congressman from black Baltimore for years. Clarence Mitchell was so influential in the U.S. Congress that he was considered to be the hundredth senator, so to speak.

And yet, as I look back on the NAACP and Clarence Mitchell, and even some of the heroic labor of Parren Mitchell, I have to consider that despite their yeoman duty, to a certain extent they had missed the boat, because once again, to reiterate, once the NAACP made that fateful decision to turn away from the international arena, we turned away from one of our most powerful allies and in a sense helped to create the setting for the rise of incarceration.

I was just in New York the other day, and as you probably know, there was yet another police killing captured on videotape, of a father, Eric Garner, 43 years old.

JAY: He choked to death.

HORNE: Choked to death with an illegal chokehold. And his last words, captured on videotape, are something of a coda, it seems to me, for black America. In other words, his last words were, “I can’t breathe.” That’s what he was saying as he was choking to death. And as I watched that videotape, it was like this enormous metaphor for the black condition in North America stretching back centuries, the suffocation, the cry of despair, the cry of horror, “I can’t breathe.”

But I should also say that the fact that so many people have come into the streets to protest against this latest outrage, this latest police killing, should also be seen as part of the coda, part of the metaphor of the black existence in North America.

JAY: Alright. This is just the beginning. Thanks for joining us.

HORNE: Oh. Thank you.

JAY: And thank you for joining us on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. And just one more time, Gerald’s book is The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America. And Gerald said he’ll come back, so we’ll pick this conversation up again soon enough. Thanks for joining us.

“Gerald Horne is an American historian who holds the John J. and Rebecca Moores Chair of History and African American Studies at the University of Houston.”