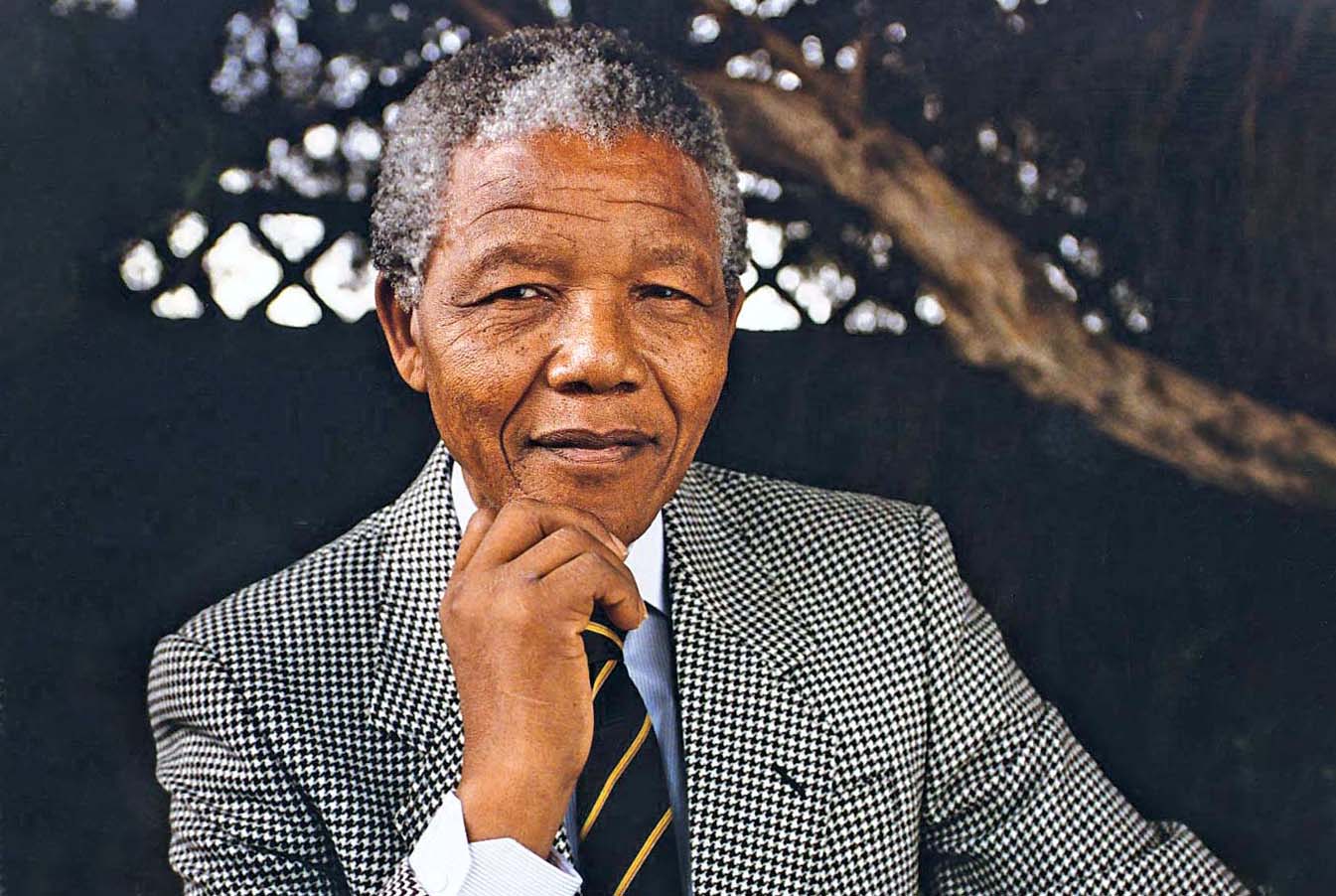

Mandela and Neoliberal Economics in South Africa – Danny Schechter (pt 2/3)

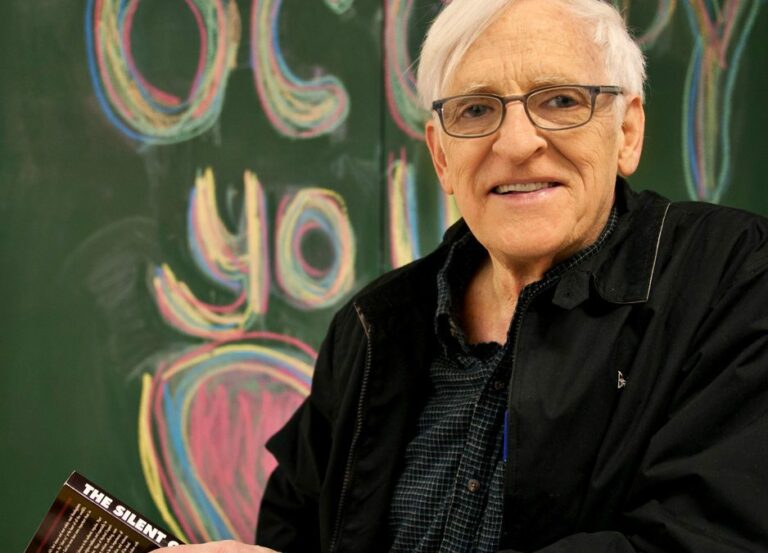

This interview was originally published on February 12, 2014. Mr. Schechter tells Paul Jay that under tremendous external pressure, the ANC gave up its plans to nationalize the mining sector.

No posts

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore. And we’re continuing our series of interviews on Reality Asserts Itself with Danny Schechter, the author of the new book Madiba A to Z: The Many Faces of Nelson Mandela.

I’m going to read a little section from the book.

“It was Mandela, too, who had crafted what was called the ‘M Plan’ (for Mandela), to prepare contingencies for the movement being forced underground. Ronnie Kasrils, who became a commander in the MK armed struggle, and later an intelligence minister, worked alongside Mandela when he was underground. He recalled: ‘He was a man of defiance. He led the masses in militant active struggle, and he led us in armed struggle. This is conveniently forgotten under the olive branch of Mandela the Saint. If one has to understand him in total, you’ve got to look back to the man who with his colleagues, with his contemporaries, created this ANC, led our people through chapters of struggle, and then at a crucial point when nonviolent struggle became an impossible way to change the system, putting his head together with others, including with young people and the rank and file, was saying, “We’ve got to find another way, and now we need to rise up with weapons.”‘”

Now joining us in the studio to discuss his book and Nelson Mandela is Danny Schechter. He’s a journalist, author, and documentary filmmaker. His films include Plunder: The Crime of Our Time. He’s currently working on a new documentary film called The Making and the Meaning of Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom. He’s written about fifteen books, including many about Mandela, and including the book I just quoted from, Madiba A to Z: The Many Faces of Nelson Mandela.

So thanks for joining us again, Danny.

DANNY SCHECHTER, EXEC. EDITOR, MEDIACHANNEL.ORG: Thank you, Paul.

JAY: So why do you think this, you could say, more revolutionary content of Nelson Mandela, the fact that he participated and helped lead armed struggle in South Africa, it’s kind of been eliminated, sanitized out of the official story of who he was?

SCHECHTER: In part that’s true, but also South Africa changed and evolved and the movement changed and evolved. Mandela said that after being in prison for all these years, he matured. He began to see that there was a need to do more than just fight back, but also to try to negotiate and engage the enemy. And he became sort of the negotiator-in-chief after being the commander-in-chief. So his strategy, his tactics, you know, evolved with the times.

This was a movement that was really a broad church movement, as they call it, made up of the unions, made up of the Communist Party, and made up of the ANC, which was more of a African nationalist type organization, and certainly not a socialist or communist organization. And he worked with Indian people, with colored people in South Africa to have a kind of common front against apartheid.

And as the leader, he was also–then in prison, he wasn’t able to be a leader. So the leadership of the movement shifted to Oliver Tambo in the Lusaka headquarters of the ANC. Mandela became a follower as much as a leader.

JAY: Before he’s arrested and he, you know, begins and calls for armed struggle, to what level did that armed struggle go? I mean, what did it look like?

SCHECHTER: Well, you know, it was an armed struggle as a concept more than as a army. It took a while for them to actually create an army, to get training, to get weapons, to–they were basically making it up as they went along. And Mandela went to North Africa in the early ’60s and was trained by the Algerians, who were then in Morocco, who were fighting against the French. And he went to Ethiopia. And he went and he got support from many African countries for the fight against apartheid. So he was, you know, both a military man but also a kind of a diplomat, a negotiator to try to bring in–foreign secretary, almost, of the ANC and its representative abroad.

So they were building this whole movement, having studied armed struggles in other countries and seeing what would work in the South African context. So, many of the activists, like Ronnie Kasrils, who you quoted, and others, began to be trained in a military organization. Mandela was at the top of it, but there were other leaders and other people involved in it. And it was a movement that started out by not attacking, not trying to kill whites, for example, but trying to engage in sabotage against targets of the regime. That’s what he was convicted of in prison, you know, and which he justified as necessary to challenge the apartheid system. So he was, you know, very clear about why he was doing what he was doing.

And a lot of that has sort of fallen away. In the movie Mandela: A Long Walk to Freedom, we do see his trial, where he’s committed, he’s prepared to die for his beliefs, and he talks about sabotage. So that hasn’t been totally sanitized out. But in the news coverage at his funeral, even though there were 91 heads of state there, it was, ironically, Barack Obama who reminded people that he had been a military leader and the head of the Umkhonto we Sizwe, or “The Spear of the Nation”, which was the name of the ANC’s military wing.

JAY: But the actual level of armed struggle did not go so far. It was mostly at the level of sabotage.

SCHECHTER: At first, inside South Africa. But then, when it became impossible for them to operate inside South Africa–a lot of their leaders were arrested and rounded up–they moved into exile and they began training people at bases in Angola, in the so-called front-line states, in Zimbabwe and in Mozambique, and their armed struggle began to move outside of South Africa proper, but still attacking South Africa when they could.

And so they–you know, it was a hard fight. And at one point the South African government invaded Angola, which is one of the neighboring states, and the Cubans came in with a military force and stopped the South African advance, working with the ANC military and the Angolan military. And that defeat of the South Africans is what led to the negotiations, well before de Klerk sat down with Mandela.

JAY: Now let’s go back to something I started in the first segment of the interview. I quoted from the Freedom Charter, and I’m going to do that again. So in 1955 they have a meeting where they establish the basic principles that the ANC is calling on the people of South Africa to support the fight for, and it includes the following:

“The national wealth of our country, the heritage of South Africans, shall be restored to the people;

“The mineral wealth beneath the soil, the Banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole;

“All other industry and trade shall be controlled to assist the wellbeing of the people;

“All people shall have equal rights to trade where they choose, to manufacture and to enter all trades, crafts and professions.”

I mean, that’s a call for nationalizing the mines of South Africa, which is, like, certainly at the time, and even now, one of the sources of the greatest wealth of the country.

SCHECHTER: Yeah, but it wasn’t necessarily the priority at that time. Fifty thousand activists under the ANC’s umbrella and flag went out into the communities, into the townships of South Africa, door to door, asking people, what would their priorities–what did they want for there to be in this Freedom Charter. So it was a very democratic, bottom-up struggle to get South Africans to express what they were concerned about.

And many were concerned about ending apartheid, ending racism, allowing black people to live decently and be paid decently and all the rest of it. There were also these other demands as well, without question. But it wasn’t, you know, at the level of, here’s our program for nationalization. It didn’t get that far. It was very generic in terms of the principles of the country being run by its majority, who are democratically–democratically elected government. It was a movement for democracy as well.

JAY: Given, but it’s very specific. It says, we’re going to nationalize the mines. And this means, we’re going down a certain kind of path in terms of how we envision the economy. And it’s certainly not the path they went down. And that’s a matter of great controversy.

SCHECHTER: Yes, it is. And, in fact, ironically, it was the Afrikaners, their oppressors, who did the first nationalizations in South Africa, nationalized sectors of the economy–broadcasting, transportation, electricity, power. All of this was done–nationalized by the Afrikaner government, not by the ANC.

But by the time the ANC became, you know, out of prison and was able to negotiate for a general election, the economic demands seemed to take a second, you know, fiddle to the political demands.

JAY: Well, that you get into a lot in your book, and I want to get there. But you agree with me that at the time in ’55–. And this is at a time when there’s a lot of politics going on in South Africa. There’s another group gets formed. In fact, there’s many other organizations that are all calling for various forms of either straightforward socialist development. And you read the language of this. Actually, this is one of the questions I had for you. They use the language of nationalization, but then later they have a quote where they go out of their way to say this isn’t socialism.

SCHECHTER: You’ve got to remember what happened in the intervening period. And this is important. The ANC in exile was supported by the Soviet Union, by East Germany, also by Sweden, but by countries that had a socialist coloration to their economies. One by one, those countries sort of fell apart. The Berlin Wall came down. The Soviet Union imploded, in a way.

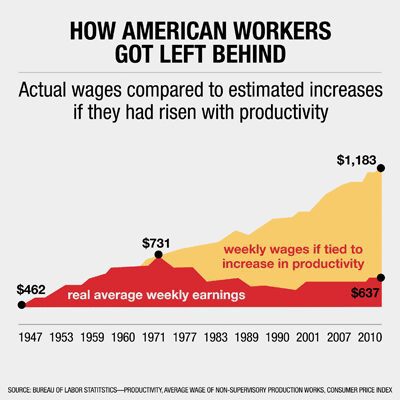

And so, as the ANC emerges as a potential government in South Africa, they have to decide what model they’re going to, you know, approach and what model they’re going to try to base themselves on. And many of the people in the movement, as well as many of their allies in socialist countries around the world, advised them: do not go in this direction, because you’ll cut off all investment, which you desperately need to create jobs. I think that they sort of bought this argument to try to be pleasers, to please the corporate interests in South Africa and around the world.

They were under a lot of American pressure, too. Mandela says the American companies were particularly strong in discouraging nationalization. You know, they had various strategists who were telling them, don’t do this, because if you do this, you’ll lose the allies that you’ve won in this fight for freedom, people like Clinton and Democrats as well.

So there was a lot of conflicting information and debate going on, and in the end they opted for a neoliberal type of economy, which I don’t think has served them well.

JAY: No, let’s–you deal with this in your book. And, in fact, there were meetings. Mandela and other leadership of the ANC, including the leadership of the Communist Party that are allied with the ANC, are meeting with Harry Oppenheimer.

SCHECHTER: Mandela was cultivating the richest people in the country. He was cultivating all the kind of support that he could get, because at the time he got out of prison, there were 35,000 armed soldiers in the apartheid army, many of them based in right-wing organizations that they were afraid would stage a kind of a Allende–you know, the kind of push that took down Allende in Chile. They wanted to make sure that there could be a democratic resolution in South Africa, a negotiated solution. And they were most concerned about this threat from the right. And so they compromised on many of these points, because they were worried that if they didn’t, the same thing would happen to them that happened to Allende and other socialist revolutionary movements in other parts of the world.

JAY: Yeah. You quote–there’s a quote in your book where Mandela’s concerned that if they don’t make these compromises, they’re going to end up in a country so destroyed, there won’t even be roads left and there will be a bloodbath.

SCHECHTER: So that was their mindset at the time. I don’t think it was based on, you know, I like capitalism more than socialism. I think it was pragmatism: what can we do now that can neutralize the far right wing in the violence in South Africa, try to end the tribal threat posed by Inkatha, the Zulu armed, you know, movement that was supported by the right? What can we do to build a new South Africa? And they thought that the U.S. and that all these other countries, like Britain, and Europe would come to their aid and help them. Ronnie Kasrils, who later has become very critical of that, you know, said at the time they were hoping for a Marshall Plan, you know, an investment in the new South Africa from these governments around the world. And it never happened.

JAY: Okay. Let me read a quote from Ronnie Kasrils, ’cause he wrote a piece in The Guardian not long ago where he’s very critical and not–he’s not so much critical of Mandela, ’cause he was part of the same–he was in the leadership and he went along with this, so you could say it’s self-critical as well. But here’s what he wrote in The Guardian:

“To break apartheid rule through negotiation, rather than a bloody civil war, seemed then an option too good to be ignored. However, at that time, the balance of power was with the ANC, and conditions were favourable for more radical change at the negotiating table than we ultimately accepted. It is by no means certain that the old order, apart from isolated rightist extremists, had the will or capability to resort to the bloody repression envisaged by Mandela’s leadership. If we had held our nerve, we could have pressed forward without making the concessions we did.”

And this “concessions”, if I understand correctly from your book and other literature, a lot of it had to do with an IMF loan that came right around this time, where you had to kind of agree to all the neoliberal reforms, privatization, give up any thought of this kind of public-sector ownership, and they went down that road. And Kasrils is saying now they didn’t have to.

SCHECHTER: Well, looking back on it, you know, you can see, we should have done this, we should have done that, woulda, coulda, shoulda. But, you know, at the time, they were facing enormous problems, you know, bringing their exiles back into South Africa, finding jobs for them, creating some basis for a democratic election, which they had never fought before and had never experienced before. They were confronting the need to train their people in how to run a modern economy, which they didn’t really have any experience with, and how to deal with the civil service, which was Afrikaner-dominated; and, you know, if you just replace experienced people with inexperienced people, you’re going to have, you know, not the outcome that you want. So they were trying to be pragmatic. And they were also under a lot of pressure from, you know, basically, the United States and other Western powers–the IMF, the World Bank–you know, that tied economic promise, promises of economic, you know, prosperity to pursuing policies that in the end undermined the potential of empowerment of the South African people. And so the poverty today is as bad as it was back then.

And so, while there have been a lot of improvements and there’s an emergence of a black middle class, you know, there’s a lot of disappointment in South Africa, a lot of a feeling of, you know, if not betrayal, of self-betrayal, that our movement didn’t do the right thing, didn’t pursue the right tactics. And this is not historically unprecedented. I mean, there’s been this–look throughout Africa, where corruption has dominated the organizations that led to liberation struggles in many other countries; and there’s corruption in the ANC as well. Once a movement goes from we, from working on behalf of all the people, to I, where people are out for themselves or out for material advantage and benefits and jobs and all the rest of it, this is what happens, unfortunately. You need a strong culture, you know, of solidarity, a culture of commitment. And that was lost in many ways.

JAY: Well, what do you make of Kasrils’–what he’s saying is they didn’t have to make as much compromise as they made. I don’t think anyone would imagine that they could come to power and immediately implement the ’55 Freedom Charter and nationalize mines. That would have been a civil war–. Let me finish my point. It would have been a civil war of massive proportions, of course. That being said, they totally embrace the neoliberal agenda. There’s no attempt, once they come to power, to even a more slow, gradual way to build up the public sector.

SCHECHTER: No. I think they had an illusion, and the illusion was, if they could take over the state and have state power and have their people in government, and even in the corporate sector, that would work to the advantage of building a movement.

They were faced with strategists who were giving them two options. One was, you know, an option of almost like Icarus flying into the sun, getting everything you want right away and then perishing; or what was called a flamingo option, where a bird takes off and flies for a long time, and that this was going to be a longer-term struggle and they realize you couldn’t do this overnight. And this was what the debate was like in those early days, about which direction to take.

They started out with a redevelopment program, a reconstruction program, and then they abandon it and they move more in a macroeconomic way, supporting the idea of banks and financial capitalism, and then they abandon that because it wasn’t working. So they’ve been experimenting with these different approaches, and at the same time trying to satisfy the desire of people for better jobs, better housing, and better schools and the like. And so this has been the conflict. That’s why you have a tremendous number of protests in South Africa against poor service delivery, against bureaucrats that are not responsive to the people, against, you know, a terrible corruption.

JAY: Please join us for the next part of our interview with Danny Schechter on Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network.

“Daniel Isaac “Danny” Schechter was an American television producer, independent filmmaker, blogger, and media critic. He wrote and spoke about many issues including apartheid, civil rights, economics, foreign policy, journalistic control and ethics, and medicine.”