Open – RAI with Bruce Cockburn (5/9)

This interview was originally published on May 28, 2019. Songwriter Bruce Cockburn discusses his experience visiting Guatemalan refugee camps and the inspiration behind his political and spiritual songwriting.

PAUL JAY: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network. And we’re continuing our discussion with singer-songwriter Bruce Cockburn. Thanks for joining us again.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Thank you.

PAUL JAY: You wanted your art to be meaningful politically, but you weren’t quite sure how effective it was. Let me quote you.

BRUCE COCKBURN: OK.

PAUL JAY: “Still, at the time, I was skeptical about the ability of music to accomplish anything in a direct way. Music can have emotional impact and it maintains an important place in the nurturing of culture and of dissent. Pinochet’s shock troops understood that when they killed Victor Jara. But a song by itself does not foment change. It’s a harbinger or a chronicle, a spark.”

BRUCE COCKBURN: Yeah, I’ll stand by that, and I think I still feel that way. What I was doing when I wrote the songs that people think of as political songs … And I suppose I could put this in the present tense, too, because it could still be happening … I’m writing what touches me. I’m trying to share that with people. This is what I’m seeing. This is how I feel about it. Take a look. Maybe you’ll feel the same way. I mean, when you’re doing any kind of art you’re not, I don’t think–most people who do art are not sitting there thinking of their audience in such specific terms when they’re creating. I mean, they may be aware of the fact that people are going to like this, or will not like this as much, or maybe they’ll be stepping out on a limb with this, or whatever.

But you were aware. I mean, if you’ve been around for a while and you have a sense of an audience, you’re aware of that audience when you’re working. But at the same time, it’s in the background. It’s just a–for me, especially–well, I guess I can only talk about me, really. It’s in the background, that. But I’m aware. I want the language to be intelligible that I use. I want people to understand what words I’m using and why, kind of. And I want to communicate those–those things that touched me with enough force that that desire to communicate is triggered. You’ve got to–you’ve got to see what this is, you can’t … We’re all familiar with that feeling. Little kids have it in spades. I mean, “Daddy look at this, look at this.” You know, and it’s basically that same sentiment. It’s just that lies behind the writing of a song. So if I go–if I’m standing in a refugee camp in the south of Mexico surrounded by a thousand Guatemalans, or 3,000 Guatemalans, who fled from horrendous things that they’re telling us about, and these people are telling us these horrendous stories with a great feeling of dignity, and of a … a kind of rise above it calm that it seems unbelievable to me, but there–but here it is, all the same, it became very poignant.

And in the case of If I Had a Rocket Launcher, I didn’t witness the attacks that were taking place. But one had happened the week before I was in this camp, and happened again a week after, I found out. But you can hear the helicopters patrolling the border. And it could have come up over the camp any time. It was only a few hundred meters away. And I just thought, in the face of all of this poignancy, that these people who are perpetrating the stuff that they were doing had forfeited any claim to humanity. And that was a very disturbing feeling. It went along with the sense of outrage, this … But I couldn’t, I noticed even then at the time, that the people who were telling me these stories did not show the same evidence of the outrage as I was feeling. They were calm. They were … They just wanted it to go away.

Now, there were other Guatemalans, of course, who chose an aggressive response to that stuff. But it’s, it was pretty interesting, the contrast there. And I ended up writing the song out of my sense of outrage and out of a sense of compassion for the people. But what made me record it–because I almost didn’t. I thought, you can’t put a song like this out in public. You know, people are going to think you’re telling them to go kill each other. And that’s not what I wanted to say to the world. But then I, you know, I had heard enough, I’d had enough discussions with Latin American writers about self-censorship that I was like–I was hesitant to not do it, also, because there it was, it was a real thing, I had done this thing and it came from a real place.

And in the end I decided, OK, the reason–what I want to share about this is, along with drawing people’s attention to the situation itself, is how easy it is for me, coming from a position of luxury, to–where nobody is threatening me–to embrace a feeling like this, that’s willing to go out and shoot people, or blow somebody’s helicopter up, in this case, you know–though I didn’t want to shoot anybody. Didn’t want to be that personal. But just–you know, to do this–these–to do an act of violence, that would have seemed to me completely legitimate.

In the big picture, you know, is anything like that ever legitimate? Sometimes it’s inescapable. But I don’t know if it’s ever legitimate. But the–in fact, I kind of don’t think it is. But the … the feelings, all feelings, are legitimate. Feelings are just feelings, if we have them. So you know, how do you go–what do you do with a feeling like that? And that’s really, you know, it was putting that song out there and inviting a discussion or a set of speculations along those lines that that justified recording the song for me.

PAUL JAY: Had you thought of yourself as a pacifist up until that point?

BRUCE COCKBURN: No. I never thought of myself as anything with an -ist or an -ism, really. I mean, I call myself a Christian, but that’s gone through many, you know, permutations. I think there was, when I was in my late teens and just starting to get into music, it made a big difference whether somebody called you a folk singer or a blues singer. Like–you know. And people used to worry about stuff like that. But once I got past that stage of my life, I–it really, you know, the definitions became kind of abhorrent, actually. I don’t–I don’t like the idea of being pinned down to an -ism, or an -ist, or being some kind of -ist.

So no, I mean, you don’t have to be a pacifist to recognize that peace is better than war. You know, I mean, anybody with a brain can see that.

PAUL JAY: But the song is saying people in affluence should not be rendering judgment on people fighting for liberation.

BRUCE COCKBURN: That’s the hope. That’s the hope, is don’t … don’t write off this component of people of, in that case Guatemalan society, that happens to have taken up arms against the oppressor of the–of their government. Don’t write them off as a bunch of radical flakes, because they come by their position very honestly. And you know, if there’s a way we can mitigate that struggle and make it less necessary for them to do that stuff, and make it end quicker, then we should do that.

PAUL JAY: The song is a real repudiation of U.S. policy in Latin America. And you write about that in the book.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Yeah. And I mean, you know, like it or not, I mean … I grew up thinking of the United States as our friendly neighbor. And in the case of Canada it has been that, almost throughout our mutual history. Not completely, but mostly. But you know, you look south and you see that since the era of the Monroe Doctrine, the United States has been up to its hips in Latin American bloodshed, basically. We–because I can say ‘we,’ because I live here, and I’ve been accepted here as a, as a resident alien. The, you know, we’ve exploited the injustices that the culture of those countries has latently or actively have for our own benefit, and perpetuated them for our own benefit. And when they didn’t–when things didn’t work out too well, and things looked like they might be getting a little better for the folks down there but it was going to cost us some money, we go in there and we blow them up.

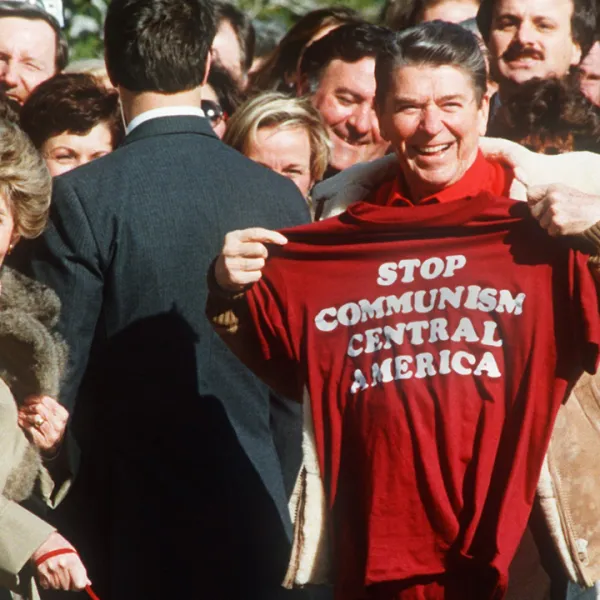

We’ve been doing this, you know, for generations. So, you know–and this is this is what’s behind the current influx of people trying to escape their situation in Central America coming to the States. And it’s–you know, we tend to downplay that aspect of immigration at this moment. But you know, in the ‘80s it was–it was active. It was real. I mean, Reagan was saying there’s no war in Central America, so there can’t be any real refugees.

But you know, it was obvious that there was war in Central America. Everybody else in the world knew it. And there were real refugees. And you know, yeah, people would like to–if they’re going to flee the place they’re in, they’d like to go to a place where they could–might have a better life. Why would you not do that? But the reasons for fleeing the place they’re in are pretty profound, and very visible if you go there.

PAUL JAY: And I think we should add Canada’s hands are certainly not clean when it comes to Latin America, from gold mining companies, to supporting the U.S.

BRUCE COCKBURN: No, I mean nobody’s hands are clean. I mean this is the thing, this is one of the reasons why it’s not good to get a swelled head about anything. We’re all in it together. We’re all–we’re all wading through the same crap and we all come out of it with the same kinds of scars. And it’s the–this is what unites us. We’ve got to recognize this. Yeah, yeah, you’re up to no good. And I’m up to no good, and we’re up to no good, but we shouldn’t be.

PAUL JAY: But it’s also a class question, no? I mean, it’s the elites of the United States that profited from all this policy in the U.S., even if there was public opinion-

BRUCE COCKBURN: Yeah, but who votes–who voted for the current elite? You know, I mean, people are–everybody is complicit. You can’t–you know, it’s true that there are people in positions of influence who could change things, who could do things a different way. And if they’re smart enough they could pull it off, and the rest of us would be happy to go along. But that isn’t what we see. Most of the people who are in the position to call the shots act out of self-interest. And they manipulate popular opinion for the furtherence of that self-interest. But—you know, the nobodies.

I like to quote–I forget his name, now. There’s some French anarchist from the late 1800s who at his trial was, you know, confronted by the judge. He said, well–he’d blown up a theater. And the judge said, well, what about all the innocent bystanders? He said: “There are no innocent bystanders.” And I mean, that’s a horrible position to take-

PAUL JAY:That’s what Bin Laden says.

BRUCE COCKBURN:That’s what?

PAUL JAY: That’s what Bin Laden says.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Well, yes, that’s what ISIS says. That’s what–I mean,it’s warped. But in the same way, though, none of us can stand back and say that we’re completely free of complicity in the bad things that go on in the world. And in recognizing our complicity, we have something in common with everybody else. We have–we have grounds for communication there.

PAUL JAY: And also stop the complicity.

BRUCE COCKBURN: Well, That’s the hope. Would be nice. But I–you know, I mean, that’s a long shot. But in the way it kind of shakes down for me is that you can-

PAUL JAY: Isn’t that what your music is to a large extent, to spark–stop the complicity?

BRUCE COCKBURN:Well, you know, in a perfect world my music would – you know, I’d write a song, and everybody’d wake up and go, “Oh, yeah, he’s right, let’s fix this.” You know, that isn’t going to happen. But what happens if you don’t do anything is that everything just gets worse faster. At the very least that’s–you’re acting against that current.

And so it matters to me to try to further the good, I think. I come by that from my upbringing and I come by that from my spiritual inclinations and experiences. And that’s–that’s my job. To the extent that it … that my job is more than just putting words on paper and then putting them to music. It’s about that. But I don’t expect it to have great impact by itself. In concert with a lot of other stuff going on that other people do it might be effective.

PAUL JAY: OK. Please join us for the continuation of our series of interviews with Bruce Cockburn on Reality Asserts Itself on the Real News Network.

“Bruce Douglas Cockburn OC is a Canadian singer-songwriter and guitarist. His song styles range from folk to jazz-influenced rock, and his lyrics cover a broad range of topics including human rights, environmental issues, politics, and Christianity.”