Peru: Mass Protests Against Hypercapitalist Narco-State Force Presidents’ Resignations

Three presidents in one week as massive youth-led protests shake Peru’s political system. Patricia Oliart, head of Latin American Studies at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom, joins Paul Jay on theAnalysis.news podcast. Produced in collaboration with Other News.

Transcript

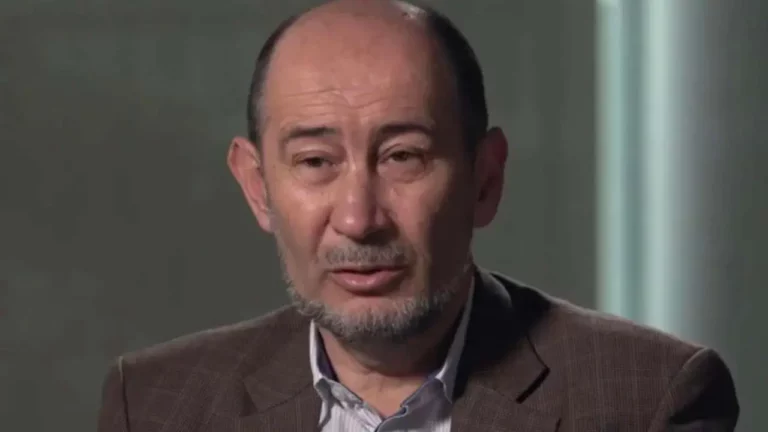

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to theanalysis.news podcast. This episode is produced in collaboration with Other News. It’s an international service that provides reporting and analysis in English, Spanish and Italian.

Three presidents in one week. Massive protests led by the youth. What’s going on in Peru? Joining us now to make sense of this is Patricia Oliart. She’s a senior lecturer in Latin American Studies and head of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies at Newcastle University in the United Kingdom. Thanks for joining us, Patricia.

Patricia Oliart

Thank you for having me.

Paul Jay

So, it wasn’t that many years ago that Peru had supposedly done this big turn-around. It was going to be one of the great stars of Latin America economically. Democracy had returned. And now, you know, at least at the level of presidential politics, it’s kind of like a basket case. Corruption is rampant. Presidents are falling left and right. So, give us some of the historical context and then we’ll get into what’s happening now.

Patricia Oliart

OK, it depends on how far back in history you want to go.

Paul Jay

Well, for a lot of people, the last thing they kind of know is Fujimori.

Patricia Oliart

The problems that led to the situation now started a bit before that. In 1985, there is substantial research showing that with the first government of Alan García, there was a sort of a seizure of the state by the mafia in Peru, particularly those in narco-trafficking and a lot of what we call the submerged economy: illegal mining, illegal logging, narco-trafficking, cocaine production and commercialization. This was linked also to the collapse of the cartels in Colombia. And it’s more or less the same people in charge of the submerged economies that with Alan García, have access to power. The mafia influence goes together with neoliberal reforms that also allow for a lot of influence for the formal economy of the state.

Paul Jay

So, by neoliberal reforms you mean privatization…?

Patricia Oliart

And the shrinking of the state, flexibilization of a lot of the laws for trade, et cetera.

Paul Jay

To what extent do the Americans have anything to do with all this?

Patricia Oliart

I think more or less at that moment, we were at the beginning of a different, global world and certainly the US had an influence. But there are other foreign interests impacting the country and also a very strong interest in oil exploration, exploitation, and also mining. And so, at that moment in the late ’80s and ’90s, it’s the world of the corporations more than specific countries. And you can see that happening in the country.

So, Alan García’s regime ended in 1990. Then Fujimori’s started. And these were ten years of demolishing of the state from within and also the growth of all these submerged economies in the different regions with certain groups gaining more influence and power. There is also a process of capturing the judiciary in the country. So, the laws don’t really work. [Laughs.]

Paul Jay

Captured by who? The narcos, the corporates or both?

Patricia Oliart

Both. It’s an alliance; it’s a tacit alliance. So, the formal sectors of the economy turn a blind eye to the other side, and the other side just creeping into every single corner they could control.

Paul Jay

Just one question about the narco gangs from Colombia. Is there, like, cocaine in Peru or they’re bringing their money from Colombia to establish themselves in Peru?

Patricia Oliart

I think Peru is among the three main producers of coca leaves in the region. So, you find coca plantations in Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia. These are the three countries where the coca plant grows. And there has been four hundred percent growth in coca plantations in Peru in the past thirty years. There is a new variety of the plant that can now grow in the lower areas, in the Amazon. That was not the case before. It used to grow mostly on the east slopes of the Andes and facing the Amazon. So, mountains versus heat and humidity. But now it is growing in lower areas and in the rainforest as well. There has been an expansion of the areas for the coca plantations and a very rapid process of we could call it “democratization” in the production of cocaine. It is not produced in labs anymore. The very growers of the plant can produce the basic paste — pasta basuca, a stage prior to refined cocaine — and then process it very quickly into kilos. There is now a huge network of mostly young people distributing these kilos of cocaine to the places on the Pacific coast where the cocaine leaves the country or through Bolivia and Brazil to the Atlantic.

Paul Jay

And I assume a lot a lot of it’s going to the United States.

Patricia Oliart

Yes. The map has changed a lot. In the ’80s, most of the market was controlled by Colombians. So, the drug produced in Peru would go to Colombia and from Colombia to the world. But with the war on drugs in Colombia, the narco-traffickers lost power in Colombia and the cartels in Mexico took control of the distribution of cocaine from South America to the US. The production of cocaine by smaller producers who are at the same time the people who in many cases also grow the plant is widespread all over the region.

Paul Jay

So, the state that emerges in the late ’90s is a merging or alliance of narco money and corporate money, a lot of which has to do with resource-extraction money. So, it’s either cocaine, resource-extraction or mining, and they’re all together building the state. OK.

Patricia Oliart

Yes, that’s more or less the scenario. In parallel with this, you have basically the disappearance of the political system that existed before the ’80s. The electoral laws facilitate access to power to all these little lords of the formal and informal economy in the country, many becoming themselves candidates. We have at the moment, I think, twelve candidates for the presidency in the country.

Paul Jay

This is in the coming elections in April, right?

Patricia Oliart

Yes.

Paul Jay

Yeah. What is it, like, half of them are under indictment for corruption for one thing or the other?

Patricia Oliart

Exactly. In Congress right now, 68 out of 130 are being [judicially] processed. Some of them even sentenced.

Paul Jay

You mean, “charged.”

Patricia Oliart

Charged; yes. And in for a wide range of crimes.

Paul Jay

Well, I don’t want to break your historical narrative, but get to the point — no rush, but how do you even get a judiciary that’s willing to charge these people? I mean, almost the whole government is involved in this kind of corruption.

Patricia Oliart

Exactly. Well, the thing is that there is a very healthy corps of civil servants in the country in spite of all of this. There are prosecutors who are trying really hard. And it is very volatile. It all depends on the support they have from the president and the alliances they form among themselves to build the cases and push them further. It’s a struggle within the state that is quite dramatic. So, the moment we are in is, in a way, the result of this healthy corps of civil servants, independent journalism, and young people.

Paul Jay

OK, we’ll get back to the present. So, pick up the narrative: we enter the 2000s with a corporate narco-state.

Patricia Oliart

Exactly. It is. We don’t dare yet to call it that. But more and more people are showing evidence of this. And so, we have the end of Fujimori —

Paul Jay

Well, talk about Fujimori for a bit here, because that’s something a lot of people know about.

Patricia Oliart

Fujimori was in power from 1990 to 2000.

Paul Jay

But this corporate narco-state evolves under Fujimori.

Patricia Oliart

Absolutely. His main adviser, Vladimiro Montesinos, now in jail, was kind of the organizer of this corrupt state. There is a famous interview with a recent president of Colombia mentioning how they discovered that Vladimiro Montesinos, this close adviser of Fujimori, was delivering arms to the FARC in Colombia because he didn’t stop short of getting involved in anything that was profitable. So, at one point during the Fujimori regime, Lima was the place where people from al Qaeda would come to get sets of passports for the world. Falsification of documents, narco-trafficking, arms dealings, you name it.

Paul Jay

I mean, my memory of Fujimori, the way the West was portraying him, was that he was this economic reformer. He was going to make the economy efficient. I mean, I don’t remember much of this being talked about at all.

Patricia Oliart

No. The narrative was that his regime brought Peru into the global financial system. At that moment, we had missions from the Inter-American Development Bank and the World Bank implementing the reform of the state. And he went along with this very happily. It was incredible because he used the money coming for the transformation of the state to gain popularity. It was money coming from abroad to push for the transformation of the Peruvian state but he used this money for partisan purposes. So, he became very popular. Because of these reforms, the state finally appeared in many places in the shape of schools, medical attention, a very interesting reform in the judiciary as well that decentralized the implementation of justice. For a lot of people, the Fujimori regime is the moment when the state finally reached the most remote corners of the country. At the same time, due to the liberalization of the economy, we get a lot of foreign investment because he relaxed the laws for giving concessions for exploration and exploitation of fossil fuels and also for mining. It is a moment where there is a lot of investment in the country and a very clear turn to being a country that exports primary resources.

Paul Jay

But under this veneer is rampant corruption.

Patricia Oliart

Exactly. From the year 2000 because of a constitution that was signed during the Fujimori regime in 1993, the political system was very severely affected. All the big political parties disappeared due to the lack of political freedom that there were in those years. Some people call these years “the era of antipolitics” in the country because they were not relevant at all. We lived within a regime that was almost a dictatorship. There was not really space for any kind of political negotiation. There was a very silent dismantling of all the unions, for example, along with the internal conflict with The Shining Path. So, it was, on one hand, state repression and on the other, the guerrilla attack on the very thick network of social grassroots organizations that we had before the 1990s. It was a moment of disarticulation of the social fabric of the country.

Paul Jay

Talk a little bit about what Shining Path was. Most people, including myself, have only the vaguest notion of it being described as a terrorist group.

Patricia Oliart

Yes, they were Maoist. Very similar to the Khmer Rouge in their ideas.

Paul Jay

Compared to who?

Patricia Oliart

The Khmer Rouge in Cambodia.

Paul Jay

Oh, really? The Khmer Rouge? Really? They were rather fanatical.

Patricia Oliart

Yes. Pol Pot. [Laughs.]

Paul Jay

The Khmer Rouge were beyond fanatical. [Laughs.]

Patricia Oliart

Exactly. They [Shining Path] were very similar in their ideas and in their demeanor as well: in the way in which they treated the communities that they managed to capture. They came out of the 1965 Sino-Soviet split. They were a small faction; part of this communist factionalizing that happened in those years. And they had a leader who was a provincial intellectual that nurtured the rage that people with frustrated expectations had for the country. Peru went through a process of rapid social mobility for disenfranchised groups in the 1960s and ’70s. But Peru is also a very racist country with no opportunities for social mobility if you are of indigenous origin. So, the Shining Path really fed into this frustration. It grew rapidly in teacher training schools, for example, a typical peasant and working-class sector for those that have access to higher education but who then are doomed to have low-paid jobs. In Peru, a teacher gets very little money. It’s the worst-paid sector in Latin America, meaning, if you compare school teacher [salaries] all over the region, Peruvian teachers are at the bottom.

So, that’s where Shining Path grew. He [i.e., Abimael Guzmán] had a very loyal and firm group of militants. They decided to engage in a popular war; they declared the war on the state in 1979. They attacked the state from its weakest point. So, the school teacher could be the enemy. And they would kill the teacher. And mayors, union leaders, grassroots leaders who were not with them. Their idea was, either with us or against us.

Paul Jay

Let me ask a question. Was Shining Path manipulated at all? I just remember Fujimori used Shining Path as the rationale for what amounted to dictatorship. If he hadn’t had Shining Path, I don’t know how he would have exercised such power. Was Shining Path really its own thing or did the state actually in any way help create the thing?

Patricia Oliart

What they did was to delay their defeat. They were smaller than the government portrayed them. But this is a narrative that comes from the secret police trying to finish The Shining Path. There are testimonies of how there were opportunities where they could have finished the organization. And it was Fujimori who delayed his [Abimael Guzmán] capture. So much so that they took advantage of a moment when Fujimori was on vacation fishing to actually capture the leader of The Shining Path. They presented Fujimori with a fait accompli. And he had to acknowledge it at his own victory. But they had to capture Abimael Guzmán without Fujimori knowing. It was a very small group in the police who performed this achievement for the country. [Laughs.] Yeah.

Paul Jay

So, how does Fujimori come to an end?

Patricia Oliart

Because of his corruption. There were a lot of protests from 1997. He won the elections in 2000, but it was clearly rigged. There was a lot of evidence of this. But still he was the president when he left the country in November, 2000. He left because someone leaked videos that his advisor had been accumulating in an incredibly well-staged scenario. He had a camera filming everybody who had power in society with him taking loads of money — actual cash — and negotiating with them: “OK, ten thousand is OK.” “OK, here you go now.” And you have newspaper owners, media officials, authorities, congressmen, people from other political parties, military men, et cetera. He even filmed a ceremony where he had several officers in the military and the police signing allegiance to the regime. And he filmed it. [Laughs.]

Paul Jay

Now, the American state liked Fujimori, right? They must have known how corrupt he was.

Patricia Oliart

I’m not sure. I think there were mixed reports from the US embassy to the US. It was clear that he wasn’t democratic. I think it depended on who was reporting what because there were clear human rights abuses, for example. And there were people from Washington who came in to assess those situations because Peru acted as an occupation army in the highlands. There were several war crimes, really, against peasant communities. So, it depends on who we’re talking about in the US. But it was certainly economically interesting because the investments were high and it was really easy to get hold of territories with rich resources in mining and oil.

Paul Jay

But also, Fujimori was seen as a figure who was very much against the left, against socialism. In fact, they even tried to equate Shining Path with some of the kind of socialist movements in other parts of Latin America. And I think the Americans liked him for that.

Patricia Oliart

Yes, he did that, indeed. He was very successful in inserting in people a deep distrust of anything progressive. So, for a few years and until the last decade, it was very difficult from anyone with progressive ideas to further their ideas or advance politically. It is something these days — it’s really nice to observe the struggle to reinstate the validity of some progressive ideas in this context.

Paul Jay

OK, so Fujimori goes down and his corruption becomes clear. What comes next?

Patricia Oliart

So, when these videos are leaked and everybody can see on television what happened, he escapes to Japan and resigns with a fax saying that he’s no longer the president. After his resignation, there were elections in Peru. We then had a series of presidents that kept more or less the same economic model of economic growth and the same constitution that favors foreign investors, lowers environmental standards, and doesn’t allow for the creation of unions. There has been a progressive loss of workers’ rights.

The whole package continued throughout the years. It’s so interesting because every election that we had since 2000 — 2006, 2011, 2016 — the candidate winning the election was the candidate opposite to the Fujimori party. But, in the end, the economic program was the same. Even in 2011, when we had an openly leftwing candidate who promised the great transformation and had a very anti-neoliberal electoral platform, once he was in power he dropped everything and said that he wasn’t going to conduct the transformation. But he had a “map” that he was going to follow, a “map” to take us to a better place. [Laughter.] But he increased repression and also concessions to mining companies, etc. So, it was more of the same.

Paul Jay

And the narco gangs still have the same kind of power?

Patricia Oliart

Yes. With the fragmentation of the political system, what you have now is similar to what happens in Mexico. Before the narco-traffickers or the submerged economy — because it’s very complex. It’s not just cocaine; it’s illegal mining mostly for gold but also other minerals that are extracted under terrible conditions all over the country; it’s illegal timber as well. In the different regions, instead of these narco-traffickers paying political parties to pass laws that favor them, what happened is that they themselves became candidates. In the regions, these people have a lot of power. They build sports stadiums, they give money for schools, they develop cheap housing. They throw their money out to their regions. They have started capturing Congress to pass laws that favor very specific aspects of their economic activity in their regions. So, Congress is like a market of very small interests where congressmen and -women negotiate their interests to have the right correlation of voting for whatever law they want to pass. So, it is a total mess.

Paul Jay

I don’t think that’s so different than what goes on in Washington, but go on.

Patricia Oliart

In 2016, we had a rightwing candidate, Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, who had worked in the US. He’d been in an executive or sitting in the directories of oil companies, etc. So, he was quite clearly a pro-neoliberal president. But he faced Fujimori’s daughter, Keiko Fujimori, in those elections. Kuczynski got the support of the majority of the population because people were saying, Fujimori? Never again. So Kuczynski got into the government. Do you know of the Odebrecht scandal from Brazil?

Paul Jay

What year we are in?

Patricia Oliart

We’re in 2016 now. So, 2018 — Kuczynski had been in power two years. And then came the president who was vacated, as we say, ten days ago.

So, what happened was that Kuczynski won [in 2016]. When he was president, something very interesting happened in the judiciary. An independent group of prosecutors started having a lot of success, more than in any other country in Latin America, following the implications of the Odebrecht scandal in Peru.

Odebrecht is a company in Brazil that had been securing concessions to carry out public works — construction, roads, dams, and all these big infrastructure projects all over Latin America — with a very perverse mechanism. They kept two sets of books: one for the projects they won and one for bribing governments to accept their projects. (What do you call it when several candidates present their plans for a project and the government has to choose? Concepción is what we call it. [Competitive bidding via RFPs, most likely.]) They had a system by which they would pay lawyers and officers to gain the concessions for their projects, sometimes pricing them with very low budgets and high technological standards so that once they got the contract for the project, they would insert addendums to the project to get more money.

In exchange for concessions they would give expensive presents to the officials involved, etc. So, everybody was smeared with this scheme. All over Latin America. In Colombia, people trying to do research on these issues have been killed. In other countries the whole investigation has been muffled. But not in Peru. In Peru, the president, Petro Pablo Kaczynski, was linked to these schemes and he resigned.

Paul Jay

And this was ten days ago?

Patricia Oliart

No, this was 2018. Right? So, he resigned. And then the Peruvian ambassador to Canada, Martín Vizcarra, became president because he was Kaczynski’s vice president. Vizcarra is an engineer from the south of Peru, from Moquegua, a good guy and an engineer wanting to serve the country. And so, he came to Peru and became president, but he was completely alone. He was not linked to any group in power, not in the formal economy or the informal economy.

He had not that progressive a discourse, but a very decent one. He wanted to fight corruption. He wanted to expand state services. He wanted to broaden the fiscal program. You know, reasonable things. He was immediately seen as an enemy by the most conservative segments of society as well as by all of the corrupt groupings. The opposition to him in Congress and in the official media was relentless. Very, very heavy.

So, ten days ago, what happened was that Congress voted to discard him as president because five people emerged to testify that he had also been corrupted by Odebrecht when he was governor in the south of Peru because he had accepted the equivalent probably of $600,000, more or less, of bribes to conduct projects. He has denied everything. He has surrendered his accounts, his passport, everything in order to be investigated. And that’s when Congress said that he couldn’t be the president with these allegations.

He’s not even being charged. There is not even a complete case against him. It’s an ongoing investigation. They did this to him twice. The first time he went with his lawyer to Congress to defend himself and he stayed in office. But two months after, when these five people emerged and start giving similar testimony about him being corrupt as well, they decided to get him out of power. And he didn’t do anything. He said he was tired; he said the investigation is ongoing and I’m not doing anything. He didn’t contest the second attempt.

So, that’s why we didn’t have a president. Then the Congress elected a guy who has very good relationships with all the little corrupt organizations currently in Congress. And he negotiated with each of them the passing laws that the executive had been rejecting because they were not viable, because they were damaging to the state.

Can I tell you what the businesses are? The minister of education is currently the head of the World Bank Division on Education, Jaime Saavedra. He’s a World Bank specialist in education. And we had him as minister of education in Peru for the past two regimes. He was minister of education with Humala, the leftwing guy who turned out neoliberal, and with Kuczynski. From the Ministry of Education, he wanted to formalize education and clean up the corruption in the education market. There are fake universities in Peru and there are fake private schools in Peru that provide really poor services and there was no system of accreditation. So, these two consecutive regimes tried to create a system of accreditation to preserve the right to a proper education to the students attending these places. They created a commission to initiate processes of accreditation for educational institutions. And this affected the mafia’s control of these really poor education businesses: for-profit universities with no credentials at all. Some of them were closed and some of the members of Congress that voted to get rid of Vizcarra are owners of these universities.

That’s one example of the kind of businesses involved. Then, because of the other investigations, there are many business people who have also been linked to contracting services with this company [Odebrecht] and also to passing rights to regional and local municipalities, etc., to gain access to these infrastructure projects. They are trying to stop the investigations of these allegations and in some cases very well-formed cases.

Paul Jay

So, ten days ago, the president resigns. The Congress elects a new one. What happened to him?

Patricia Oliart

What happened was that as soon as he was elected, people went into the streets because the rage in the country at having these mafias in power is enormous. This is why we have been voting every time for whoever we saw as not representing the mafias. So, whoever had an agenda of fighting corruption, we voted for — regardless even of the program they presented. Whoever said, “Stop corruption; this is it! Done. I am going after this and that…” We voted for this person because the rest are quite poor and empty. [Laughs.] And you can see the little corrupted people participating in the elections with sometimes plagiarized government programs. It’s really miserable. So, when these people won and got rid of the president, people went into the streets.

During the protests two young men died because the police were in the streets to kill. There are videos of policemen saying, “Kill him, kill him!” You know, that kind of thing, shooting at the body. It was not just teargas, but there were also rubber bullets, but they are 80 percent lead.

Paul Jay

That ain’t rubber! [Laughs.]

Patricia Oliart

Right? The coating is rubber, but 80 percent of the bullet is lead.

Paul Jay

And two students were killed.

Patricia Oliart

Yes. After they died, the people filled the streets with the largest protest movement ever seen in the country. In Lima, for example, in previous years, you would see fifty thousand people in one plaza and some other people marching in the streets. This time, last Sunday, you had similar amounts of people in different districts in Lima, in the smallest towns in Peru — the whole country was out. There was a survey that says that thirteen percent of the population was in the streets, not counting, because of the pandemic, people banging pots from their houses, hanging banners in their houses — or people under 18 who were a large proportion of the people attending these marches because of the situation of pauperization [phon.] that corruption has contributed to in the country together with neoliberalism. So, if you want, in Peru, the struggle against neoliberalism is linked to the fight against corruption.

Paul Jay

And most of the people in the streets were young? Is that right?

Patricia Oliart

They were very salient. And what I think makes them visible is that, because of the protest culture that has developed globally, they took control of the shape of the manifestation and its endurance. They gave it stamina and a lot of energy. But you have people in wheelchairs in the streets. It was a massive multigenerational manifestation of discontent.

Paul Jay

And social media played a big role.

Patricia Oliart

Social media played a crucial role because we don’t have political parties. We don’t have unions. So online communities — gamers, skaters, Tik-Tokkers, K-poppers were articulating the protest, giving people ideas of where to gather, giving georeference locations of where the police were, organizing brigades to advance in the streets with Hong Kong techniques of using shields and laser beams to confuse the police. Everything you can imagine, and all learned from the Chilean upheaval from last year and from Hong Kong. Crashing media websites, hacking Congressional web pages — the Congress’s page was hacked. All this global protest culture was used massively in these protests and made them very, very effective.

Paul Jay

Then the president had to resign under the pressure of these protests.

Patricia Oliart

Exactly.

Paul Jay

And so where are we now? Who’s president and what’s next here?

Patricia Oliart

In Congress, when they decided to get rid of Vizcarra, the vote was 105 to 19 for ousting him. Because something like this happened exactly 20 years ago, the new president can’t be anyone in the group that voted to remove the old president. None of the 105 could be the next president, so the next president needed to come from the 19 who voted against the elimination of Vizcarra.

And so, that’s how we now have a very interesting group of people. We have Francisco Sagasti as our president now. He is an engineer and philosopher, an expert in scientific and technological development. He served in the World Bank, in different branches of government in Peru, mostly linked to science and technology. He is a very well-mannered man and he knows how to establish dialogue. And so, he was accepted by most of the Congress in order to make the country governable. So, we have him in power now. The president of Congress is a lawyer and an activist for peasants’ rights confronting mining companies. She has won twice against the Buenaventura mining company defending people who are resisting selling their land to big mining projects. And she’s a human rights activist, and from the left. She’s the president of Congress now. And that’s where we are. [Laughs.]

Paul Jay

And that’s where we are. [Laughs.]

Patricia Oliart

Yes.

Paul Jay

And are the youth and other people still in the streets or not? The protests continue?

Patricia Oliart

Yes. Protests continue for two reasons. One is that people want a clear investigation about the particularities of the presence of the police during these last ten days, because we have never seen anything that violent. In a few days, around 50 people were disappeared. They were kidnapped by the police, imprisoned with no formal charges, with no prosecutor present, and tortured as well. Had it not been for human rights organizations that really canvassed the whole city looking for them, they would probably be dead now or still disappeared. There are no disappeared at the moment due to the pressure from civil society and human rights organizations.

But there is no clear decision yet from the new government about how to deal with this, how to establish criminal responsibility for people who acted in this way. At the moment, they are all avoiding responsibility. And so, people are in the streets because they want clarity, people held responsible, and also compensation for the families of not just the two kids who were killed, but also of 102 severely wounded people — bullets to the head, paralyzed by bullets to the back. Terrible. The damage has been terrible. The new president has visited some of these wounded people in hospitals, but there’s still nothing clear about who is going to take responsibility for this.

Paul Jay

And this is all happening during the Covid pandemic. If I understand correctly, Peru has maybe the second highest per capita mortality rate in the world. Because I guess in the midst of all this chaos, how can there be any real control over the pandemic?

Patricia Oliart

Exactly. Well, one of the terrible things that happened from the start and that is also linked to corruption was that we didn’t really have a proper health system. Formally, we have universal coverage. But if you are ill and go to a public hospital, you need to take a relative to take care of you because there are no nurses, your own bedding, and you need to buy medicines wherever you can because hospitals are really poor. So, we have the system. We have the doctors. But nothing else.

Paul Jay

I saw the same thing in Afghanistan in 2002. We found a kid whose head had been split open and he needed stitches, but we had to run down the street to buy sutures to do the stitching because they didn’t have anything to stitch with.

Patricia Oliart

Exactly. So Vizcarra, the former president — from ten days ago — knew this. And this is why Peru had one of the quickest reactions to the pandemic, very strict measures of confinement, etc., because the system was not going to be able to respond. And yet, even in these circumstances, we still saw corruption within the state. A person working in a public hospital who had just received medicines to treat Covid stole medicines in order to take them to her own pharmacy. So, that kind of thing. Or a relative of the governor in Iquitos, who had just had oxygen flown in to treat patients, stole the oxygen tanks in order to sell them privately. Corruption is absolutely generalized and this has also hindered the intentions of the government to respond to Covid.

Paul Jay

Is there a progressive political formation that could emerge as an alternative out of this protest movement?

Patricia Oliart

What is interesting is that I told you about the first reason why people are in the streets. The second reason why people are in the streets now is because the understanding is growing that Fujimori’s constitution of 1993 is at the root of all the evil things happening to Peruvians. This constitution creates a political party system that allows for this fragmentation and the election of corrupt people because in this voting system when you vote for congress, you vote for individuals and not for political parties.

The other thing is that due to the constitution the state has very little power to stop monopolies. For example, one company owns 80 percent of pharmacies in the country. And the government can’t do anything about that because of the constitution. It’s at the root of several of our evils. People see the need for change in the constitution, and we just have what happened in Chile where a change of the constitution was at the root of the of the movement, of the upheaval. And so, this idea is growing.

Another thing that is happening is that people are starting to understand that being leftwing or progressive doesn’t make you a terrorist, which is the idea that Fujimori instilled very deep in people’s fears because the experience of the armed conflict [with Shining Path] was traumatic for many people. And everybody saw it as linked to socialist ideas. It’s interesting that these days is that anti-progressive ideas are losing prestige at the moment and people don’t believe them anymore. People are being more critical these days of fake news and all these rightwing, very conservative ideas that demonize anyone who talks of progressive changes.

So, something nice may happen out of this. We have elections in April next year. Some people are saying that that could be the moment to change the constitution. But we still have people in the streets because of the human rights issue but also because there is a growing demand for change in the 1993 constitution.

We don’t know what is going to happen. And it is not clear yet how the president is going to tackle the opposition from the streets. He started his first address to the nation acknowledging the importance of political participation of people in the streets. He acknowledged the dead kids. On behalf of the state, he apologized to the nation for these events. But it is not clear yet what he’s going to do about that either. On the constitution, he has not said a word about it.

What he’s saying is that his main commitment is that in the months that he has before April, he wants to have clear, transparent elections and he wants to fight Covid. Those two are his priorities. That’s what he wants to do. It’s very interesting because he had called for a cabinet full of a really interesting range of people with trajectory in the state. Several of them either have served as ministers in previous regimes or have been vice ministers. And so it’s a very competent team that is seen by the right wing, as leftwing, socialist, communist Chavistas, or whatever. But they are all really interesting professionals — many of them with no qualms about neoliberal economic plans or whatever.

Paul Jay

What do you mean by, “No qualms?” No qualms about being neoliberal or being anti-neoliberal?

Patricia Oliart

Being neoliberal.

Paul Jay

So, it’s a very centrist group.

Patricia Oliart

Exactly. It’s a centrist cabinet.

Paul Jay

But I suppose if they’re not rabidly corrupt, that’s a move in the right direction.

Patricia Oliart

I think that’s the major gain of this whole thing.

Paul Jay

I saw that Peru’s GDP has gone down by 14 percent since the pandemic hit. So, with a high mortality rate and high unemployment, the way that this is going, the economy is going to get worse. Listen, we’ll come back to you, Patricia. In a few weeks, we’ll come back and we’ll talk again and catch up where things are.

Patricia Oliart

OK, well, thank you.

Paul Jay

And thank you so much for doing this. And thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news podcast. Please don’t forget we’ve got this fundraising campaign going on. We have a $10,000 matching grant. If you give a buck, we’ll get it matched. If you donate monthly, that will get matched. And thanks for joining us on theAnalysis.news.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download