Plundering Our Freedom with Abandon – Robert Scheer (pt 5/10)

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on June 24, 2015.

On Reality Asserts Itself, Mr. Scheer discusses American partisan politics, is there a real difference, and the demonization of the other camp.

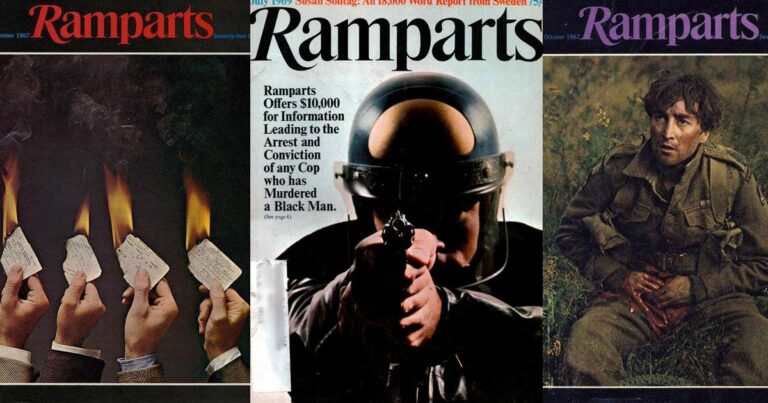

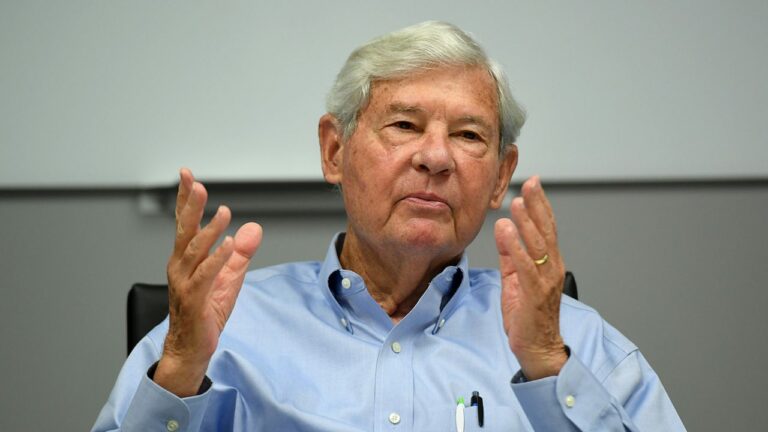

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network and Reality Asserts Itself. I’m Paul Jay. And we’re continuing our series of interviews with Robert Scheer. He now joins us again in the studio. Thanks for joining us again, Bob. So just to remind everybody, Bob is a veteran U.S. journalist, currently the editor-in-chief of the multi Webby Award winning online magazine Truthdig. But Bob was also a correspondent and editor for a while, if I’m correct, of Ramparts magazine. Ramparts is a historic journal from the Vietnam era, Vietnam War era. So thanks for joining us. Tell us, after Ramparts, you’re kind of a fairly well known writer and you go on to some big-name publications, and amongst other things, you start interviewing presidents.

SCHEER: Well, I interviewed–the first big interview I did after Ramparts was Jimmy Carter. And that’s where he talked about the lust in his heart, and it almost derailed him in the ’76 election. But I was also profiling Nelson Rockefeller, who was vice president. I profiled a lot of people in those days. And, yeah, so my–the interview became my art form. And I’ve always liked the interview. I think it’s a real challenge. When I’ve taught classes in the art of the interview, I think the key is to get yourself psyched up that you actually could be wrong or not know something or need this person you’re interviewing to help you understand. And that is an absolutely essential ingredient for a good interview.

JAY: So I know you are a thinking person, not just a journalist. I say that in all seriousness, ’cause a lot of journalists have fairly narrow tunnels about how they do their investigative work, and you do a lot of thinking about society. Talk about the end of the–you know, the post-Vietnam period. What happened to the antiwar movement? Why do you think the mass movements of the ’60s, why there was such an ebb?

SCHEER: Well, I think the main thing is that they did away with the draft. I think the people who run this country decided if they’re going to effectively wage wars, they have to figure out a way of avoiding drafting ordinary Americans, have a professional army, rely on high tech–I think drone warfare is this sort of ideal, ’cause the only people that get killed are innocent or guilty others, not people from Ohio or–. You know.

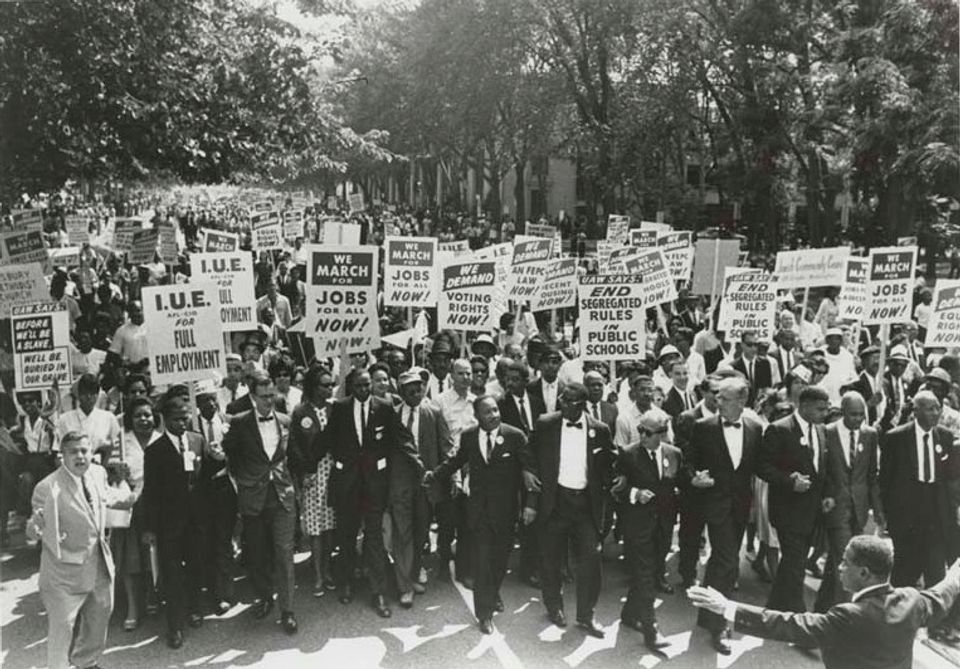

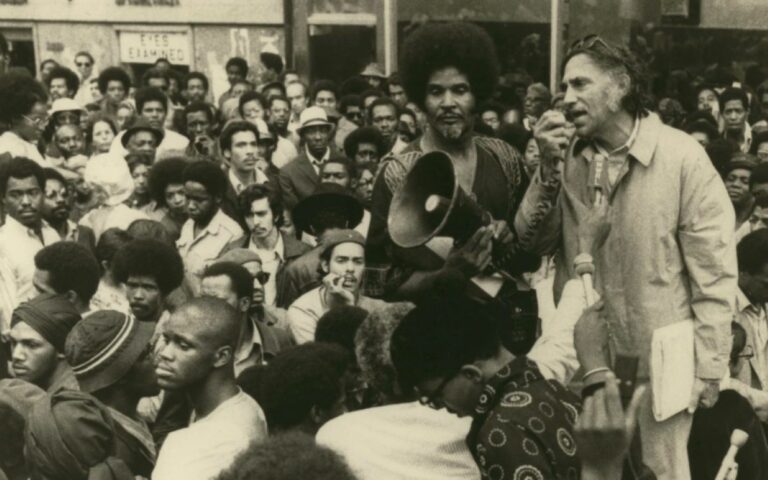

JAY: But the antiwar movement was–the demands of the antiwar movement went beyond the draft. The civil rights movement demands certainly went beyond the concessions that were won. Even the workers movement was very militant during the ’60s. There were many, many strikes. In fact, in many unions, although some unions were quite conservative in support of the war, there was a growing union movement that was antiwar. There was a radicalization taking place throughout the society. And then it kind of fizzled.

SCHEER: Well, think co-option is the key thing here. I think people who have power in this country realized that they were being arrogant in their confidence that they can manipulate the public. They had the big newspapers, television. They had the toys to dispense. And they thought they could sort of dictate the terms and get away with it, would not be questioned. And they realized that, first of all, you had more people who had time to think and were going to college, had some leisure time, could–you know, you had people at schools who could raise questions. You had teach-ins. The assumptions of the society could be examined. You had people like Howard Zinn coming out with books saying American history is not so rosy, there are real issues and contradictions and so forth. And I think they felt–and by they I’m pretty clear, ’cause I interviewed a lot of these people. You know, Nelson Rockefeller had his commission on critical choices. I mean, they actually thought about this stuff. Are we losing our grip on the society? You know, what’s going on here? How do we keep the young? You know, when John Lennon becomes a real menace, you know, from The Beatles, instead of being one of the lovables, he becomes a critic, he’s talking about peace and war and race and “Working Class Hero” and–you know, one of his songs and everything.

LENON: Keep you doped with religion and sex and TV / And you think you’re so clever and classless and free / But you’re still fucking peasants as far as I can see / A working class hero is something to be

SCHEER: you start to think, wait a minute, we have a PR problem of a major dimension here. And so the real question is: how do we cool out the population? How do we manipulate, how do we control it? And you have to be more sophisticated about it, right? And that sophistication involved, you know, buying out. I think the whole professor class got bought out with tenure and good salaries.

JAY: Much of the union leadership.

SCHEER: Well, but I’m just [incompr.] first of all the intellectual class. There were enough openings to interesting artists, and people could get wealthy, and so forth. The union movement got divided over the Cold War, and the old-fashioned Meany labor unions and so forth just basically didn’t go anywhere. And you passed legislation making their lives much more difficult, making it harder to organize, harder to get people to sign up, you know, in the name of freedom. So there was a lot of that kind of thing. But basically you avoided certain traps. You could not use the basic American population as cannon fodder. They wouldn’t go for it. So you had to have another way of waging wars–more covert actions, more using other people’s armies, high-tech fighting mechanisms. They don’t work very well, because without boots on the ground, it’s hard to control Iraqi soil. You can have a surge and do well, as the Republicans point out, but then you can’t keep up the surge. And, you know, we still haven’t won in–we haven’t won any of these wars. You know, we can overthrow Qaddafi in Libya, we can maybe overthrow Assad in Syria, but you seem to get something worse. So, you know, they’re caught between different models. What is your model? You don’t want to really run the world. You can’t. It’s not cost-effective. And you’re up against someone like China. What are the Chinese doing? As opposed to our prediction, they’re not conquering anybody. They’re just making deals. They’re making shrewd investments. They’re buying stuff cheap. They’re figuring out how to do stuff themselves. I mean, when I was in the Center for Chinese Studies, the assumption was China could never develop. It had 400 million people, and the conventional wisdom was that was too big a population for that land. The land had been worked too much. They didn’t really have much in the way of natural resources. And because of this huge population, they couldn’t go anywhere. People like Ehrlich wrote The Population Bomb and everything. You know, [it was going to sink. (?)] Well, the Chinese have defied all of that. They’re still a Communist government, but they haven’t followed a model of conquest. They’ve been very shrewd in delivering certain things to their own people. They’ve had this incredible–it’s like the enclosure movement in England without the turmoil. They’ve been able to move hundreds of millions of people off the land into cities and somehow keep some stability without the upheaval you had in Europe. And at the same time, they made deals all over for the stuff they don’t have, all the oil and minerals that they really don’t have in China. They seem to be quite shrewd about it. And they’ve done this without a very large military. We still have a military equal to–you know, we spend on the military equal to the rest of the world combined. The Chinese are basically developing a regional force that–.

JAY: Just to pick up the point you made about the difficulty of manipulating American people to be fodder, that was something they needed to grapple with, because with such a militarized economy and such an economy based on dominance around the world of one form or another relying on the military, there was a whole issue of how to get Americans ready for war again.

SCHEER: Look, there’s two different models. You know, one you can actually believe in international capitalism, and some are going to succeed, some not. Some American companies are going to succeed, some not. You know, General Electric is a company that basically went from being a national, American-as-apple-pie company making good stuff here with American workers to basically being an international operator, two out of three jobs outside of our country for much of the ’80s and ’90s, well, right up till the great crash. Increasingly, their business was banking, GE Capital, loans, subsidized mortgages, you know, exploitive mortgages, and so forth. Now they’re suddenly getting out of that business. So a lot of that happened with General Motors, GMAC, you know, a lot of loan financing, a lot of financial dealing, and then outsourcing a lot of the production of cars to try to be more competitive. So you can have a model of how you operate internationally. Certainly Apple has a very successful model, that mixture of producing things abroad, but opening markets abroad, gradual improvement of wages in some markets so people can buy your stuff. I think what’s happening in China with Apple is quite interesting. It’s a model that basically challenges the very notion of the nation state. You know, you don’t need the Marines to come in and–. No. I mean, don’t you could argue. I think that right now you could argue that for Apple or for Google, the U.S. government is an embarrassment, the surveillance society is an embarrassment. Whatever the value of it was at first, right now Google is having a hard time penetrating the Chinese market. And the Chinese government can say, trust our companies, the devil you know. You know. And Apple is more successful in China because they are responsive to domestic Chinese interests. There’s a gradual improvement of wages [crosstalk]

JAY: Yeah, and certainly for some of the technology companies, maybe it’s not as direct, but for many sectors of the American economy, the connection between U.S. foreign policy, U.S. military power, and commerce are inseparable, so the fossil fuels and others.

SCHEER: I don’t know if that’s true. I mean, look, as I say, there are basically two models. They have risks and problems. But, for example, right now California’s having a problem with it’s almond crop because it needs a lot of water to grow almonds. But the fact is, people all over the world want to buy those bloody almonds. You know? Now, maybe the price can go up and they can have both the water and the almonds. But the fact is we have in California very rich agriculture that seems to work well in the world. And there are–and we have the tech industry. We have a good climate in California, so a lot of immigrants come and keep land values up and housing. I mean, if you–you know, I live in Los Angeles, and we are basically not an Anglo city. I mean, we have huge populations from all, including Canadians, but we have Iranians and you can go into huge restaurants where people are speaking only Mandarin.

JAY: But [if you don’t think (?)] that this massive military machine isn’t connected to U.S. Congress, then why have such a massive military machine?

SCHEER: I think it’s an anachronism. I really do. I think it’s an old-fashioned model of the imperial state that benefits, obviously, in some ways, Boeing and Lockheed and, you know, defense contractors. But even they have their own contradiction, ’cause they also have civilian wings. And I think we’re in a period of adjustment. And in that adjustment you have to accept that you’re a normal state, you’re not the city on the hill, you don’t control the whole world, you can’t control everything, kind of the wisdom of the framers of our Constitution that did not envision an empire and thought that was a real trap, to build an empire, and that’s what destroyed Rome and destroyed England and so forth. And we are really fighting between these different models. I am not of the school that says without a big military the U.S. would be a third-rate nation. No. We have great resources. We have a hard-working population. You know, we have a lot going for us, very good climate. We’re centrally located for a lot of things around us. And I think one can make an argument, which is the argument, I guess, George Washington was making, that, you know, use gentle means, engage in normal commerce, don’t try to exploit and conquer people, and you can do quite well. We’re not going to be a banana republic. We can do things other than grow bananas.

JAY: You may be right, but certainly the preponderance of the American military, foreign policy, and business elite don’t believe so. I mean, they believe that there needs to be regime change when you want to. In fact, if anything, it’s going more the other way.

SCHEER: Well, it’s a conflict. It’s a big conflict.

JAY: Right now, with the lack of opposition of another superpower, if anything the mentality is the ability to assert American foreign-policy interests through military is even heightened now.

SCHEER: I understand. But military is a loser.

JAY: I’m not saying it’s rational.

SCHEER: Imperialism is a loser. So you have a conflict. As we are recording this–I don’t know when you’re going to show it, but right now, we’re towards the end of April, and right now the secretary of defense has spent the whole–our secretary, Ashton Carter, spent the whole week in Silicon Valley trying, without much success, to convince the people in Silicon Valley they should be part of the American military machine. He’s given one speech after another. And he’s found resistance right across Silicon Valley, because these people feel now that their association–which has been intimate, with the military, ’cause after all, the internet came out of a military project and there’ve been military contracts. But now this whole attempt to use cyber warfare and have a whole new chapter of the Cold War around cyber warfare and you need us and we need you to improve this and all that, they’re finding tremendous resistance, tremendous resistance, because it undermines Facebook’s model. Facebook needs growth internationally and they need the trust of people internationally. And Google needs the trust. Use our search engine. It’s a neutral engine. It doesn’t favor American culture or American business or the American military, right? It’s universal.

JAY: Well, I mean, I haven’t studied this, so I can’t get into any argument with you, but people I know–.

SCHEER: Well, people should read my book, ’cause it’s really about that, and, you know, They Know Everything About You. But the positive side–.

JAY: Most people I know in the tech sector, they say, a lot of them say that Google and some of the others are putting on this kind of show of pushing back, but in reality NSA and the surveillance programs have had lots of access and they don’t really push back that hard.

SCHEER: Well, until Edward Snowden, which is–you know, it’s like before Christ and after; I mean, I’m not saying Snowden’s Christ, but it’s a critical moment in the life of Silicon Valley–you could get away with doing both things. You know, you could claim to be neutral to the world, and we’re just Google, we do no harm. Right? You’ve seen Google ads and Apple. We’re just, you know, for everyone, and all we want to do is sell you good products and service your interests, and yet at the same time be playing footsie with the U.S. military, which they were doing, and getting military contracts and so forth. But let me just be clear about this. After Snowden, after this knowledge comes out, you can’t get away with it. Whatever you want to do, it doesn’t matter. You cannot get away with it.

JAY: Why not?

SCHEER: Because people now when they see a little Google truck running around Hamburg taking pictures of their house, they know it’s the CIA taking pictures of their house, and they don’t have the same benign view of the American CIA and NSA, which, after all, tapped Angela Merkel’s phone, right? So there’s–the pushback is very real. And if you have–Google has 90 percent of the European market. If they lose that market, they go the way of IBM and Microsoft. These companies can decline. They all live in fear of decline, because they’ve seen it with once great companies. And now three of the top ten tech companies, tech product companies, are Chinese. And so what do these folks say? Hey, you know, you can trust us more than those guys. At least we speak your language.

JAY: But it seems to me what you’re suggesting or what you’re hoping is that there’s still some rationality left in the system.

SCHEER: Well, there’s rationality left in consumers and in human beings.

JAY: But is there any rationality left in the elites and in the system itself? Like, for example, you can–.

SCHEER: Tim Cook is a member of the elite. He’s very rational. Very rational.

JAY: No, I’m not saying there aren’t some individuals.

SCHEER: Yeah.

JAY: What I am saying is take for example banking. I mean, you did a whole book on banking. In fact, take for example banking–and, in fact, we’re going to stop here and do another segment, and we’ll pick up this whole issue of rationality, the system, and we’ll start with banking. So please join us for the continuation of Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News Network with Bob Scheer, and maybe we’ll argue a bit more.

“Robert Scheer is an American left-wing journalist who has written for Ramparts, the Los Angeles Times, Playboy, Hustler Magazine, Truthdig, Scheerpost, and other publications, as well as having written many books.