Pollin: Nationalize Fossil Fuels and Create Public Banks

The collapse of oil prices is an opportunity for a public takeover of the fossil fuel industry and replace it with sustainable energy. As the depression deepens, it is also the time for large publicly owned banks to weaken the economic and political power of finance. Economist Robert Pollin joins Paul Jay on theAnalysis.news podcast.

Paul Jay: Hi, I’m Paul Jay, and welcome to the analysis podcast. In a speech that President Roosevelt gave in 1932, talking about the Republicans and financial elites of his day, FDR said, “I read somewhere in a history book about a Roman senator who threw himself into a chasm to save his country. These gentlemen who represent us are of a new breed. They’re willing to throw their country into a chasm to save themselves.”

That seems to describe the American oligarchy today with save themselves, meaning save a system that has created unprecedented wealth, going to a tiny fraction of the society in spite of the cataclysmic threats of climate change and nuclear war.

Biden claims he wants to create the most progressive administration since Roosevelt. He should read some of Roosevelt’s speeches on concentration of corporate ownership and fascism to see what that would mean.

Now joining us is Bob Pollin. He’s co-founder of the PERI Institute. That’s the Political Economy Research Institute in Amherst, Massachusetts and author of an upcoming book co-authored with Noam Chomsky, titled “Climate Crisis and the Global Green New Deal, The Political Economy of Saving the Planet. “Thanks for joining us, Bob.

Robert Pollin: I’m very happy to be on, Paul. Thank you.”

Paul Jay: Well, let’s start with sort of the obvious big question. Given Covid, given the crisis, just how deep is this economic crisis going to be? How long might it last? What are we really looking at? Are we really looking at unemployment levels that equal the Great Depression or worse?“

Robert Pollin: Well, you know, the fairest answer, I think, is we don’t know. And the mere fact of the extreme uncertainty that we face certainly suggests ,that alone, is a crisis because you can’t operate a capitalist economy effectively with these massive levels of uncertainty. So, you know, there’s a lot of things. Most things we just don’t know. I mean, I can tell you where we are now as of today, as of April, 23rd, the latest figures on unemployment insurance claims, initial claims over the last five weeks.

We are now up to 25 million. So that’s 15 percent of the labor force. That’s not the official unemployment statistics, but it’s probably a better metric anyway. So in the Great Recession, what we call it, the Great Recession of a decade or so ago, unemployment never got beyond 10.2 percent. Now it’s at roughly 15 percent already.

So it could keep going up. If we continue with the lockdown, it almost certainly will go up. On the other hand, one of the things that the capitalists have learned over the decades, if they don’t know how to do anything else, they do know about bailing themselves out, and the bailouts for Wall Street and corporations are absolutely gigantic. They probably are not enough. They almost certainly are not enough. But nevertheless, they’re gigantic. I mean, we have the first stimulus package, the, ”Pear’s” package of the past couple of weeks ago, was two trillion. So that was 10 percent of GDP. The money that was supposed to go to small business, the three hundred and fifty billion in loans that could be converted into grants that got used up in one day. So now, you know, as of yesterday, the Congress has passed another one, another 400 billion or so for small business. On top of that, you had the Fed standing ready to give unprecedented loans to corporations and Wall Street and to buy assets, to buy corporate bonds and government bonds held by Wall Street firms.

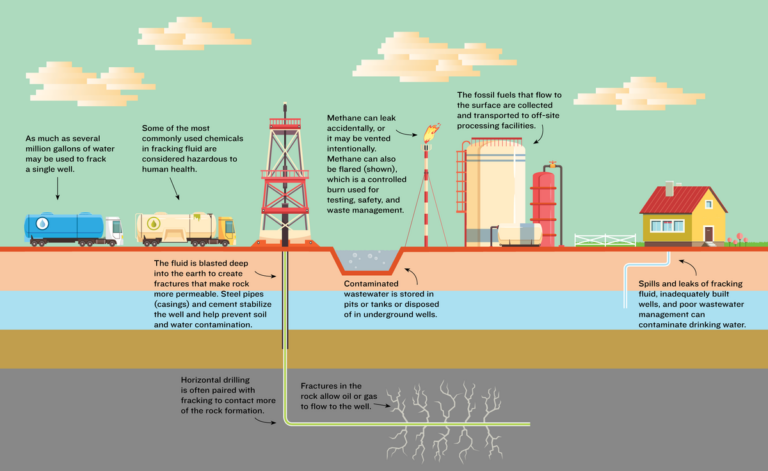

And, you know, if you believe the Financial Times, the amount of purchasing they’re they’re looking at is probably in the range of six to eight trillion dollars. So we’re talking about like 35, 40 percent of GDP injected into the economy in a matter of weeks, maybe months. So, I have to believe that this is going to prevent something equivalent to the 1930s depression when we didn’t know how to do these things. They let the banking system fail so that the capitalist foundation to a large extent, is going to be protected deeply. Nevertheless, the severity of the crisis is pulling the other way. So we know that the oil companies, fossil fuel companies, they’ve lost half their value since the beginning of the year. They now are literally not only giving away oil, they are paying people to take oil.

Paul Jay: So that’s because their storage facilities are full. The storage facilities that are used up. They don’t know what to do with it. And so, by the way, that would suggest the oil industry is ripe for nationalization.

But overall, I think my best guess is that this is going to be a recession comparable in in its worst phases in severity to the Great Depression. But it’s only going to last maybe eight or nine months, and then things will recover. I mean, “recover. “It’ll be a very slow, uneven. And the nature of the recovery will depend on the political configuration that comes out of the next few months.

Paul Jay: WHO and the head of the CDC are saying next winter could be worse than what we have just gone through.

Robert Pollin: Yeah, well, you know, I don’t. I’m certainly no expert on pandemics. I also just read that the WHO is projecting 10 million infections in Africa over the next three to six months. They basically have had none so far. There’s only been 12000 recorded. Now we’re talking about getting to 10 million. And, you know, they’re actually, there was a paper from the African Economic Research Consortium just yesterday that they themselves saying, look, we don’t have any health care resources to handle this. So if there is anything close to 10 million, you’re going to see people dying in the streets. You’re going to see mass starvation. So if that’s the case, then all bets are off. I mean, you know, it’s just absolutely unprecedented. Maybe we have to go back to the 14th century. To the Black Plague.

Paul Jay: Yeah. And massive attempted migration. So then you’re gonna get the kind of migration we’ve seen to Europe in the last few years times. Who knows what? It’s going to be insane. And then Latin America, you look at all the barrios, the slums all throughout Latin America. That’s starting there. And as it starts to develop, you can have a similar situation as Africa. And they’re talking about a second wave in China. I know I’m going on with worst case scenarios, but that’s what scientists now say.

Robert Pollin: I think, I think, you know, we don’t know. I mean, those are realistic scenarios. And I mean, let’s say it’s a lot worse. It’s a lot less bad than what you’re suggesting. But it’s still horrible. Catastrophic.

Just on the economic front. If we are operating in semi lockdown for not I mean, I’m saying, you know, maybe four or five more months. But what if it’s 10 months, you know? And then the U.S. unemployment is at 20 percent. Twenty-five percent for 10 months, 11 months. And then really, who knows? Things are going to collapse. We’ve got 30 million small businesses. What if 70 percent of them go out and, you know, go under.

Paul Jay: There’s a quote from Roosevelt in the 30s where he talks about lending money to business to keep them going during this crisis is not enough. The government has to do something about the purchasing side, that people have to be able to buy things. How much of these trillions, so much of it that’s going to the corporations? Some of it’s going as direct payments to people, at least for what is it, 16 weeks or something?

Robert Pollin: Yeah.

Paul Jay: But how much of that money is directly connected to them continuing to hire and pay people even if they’re not able to work, or not? How strictly is that going to be regulated?

Robert Pollin: Well, the money that’s going for, you know, the General Lending Fund, which is basically for big business and the Wall Street stuff there, there’re no stipulations attached. So the businesses can take the money and lay off all their workers, basically. I mean, there’re some weak conditions, but they can be overturned by the Treasury Secretary. .The Fed stuff. There’s no conditions whatsoever. The small business program, it does have the condition that it can convert loans. Loans can be converted to grants, outright grants of money, if the businesses keep their payrolls intact. So that is an incentive. But there are a couple of other stipulations.

And so businesses. I’ve read some articles where the small businesses don’t really believe that they are going to be eligible for this. And so they’re worried about it. The best proposal out there is the one by Congresswoman Jayapal and the Progressive Caucus. the Democrats in Congress. This basically provides 100 percent of payroll grants to any business. So we’re going to, the government is going to cover your payroll as long as this crisis continues. And that way one thing businesses don’t have to worry about, whether they’re going to qualify under the small business provisions. They’re not going to be loaded up with debt. I mean, even big corporations, if this goes on for six months and they have no revenue coming out of it, the recovery will be really limited because the heavy debt levels has been piled up while the businesses had no revenue. So this way the businesses get their full payroll. The deal is, of course, that they have to keep everybody and their jobs so that there’s no increase in unemployment. Everybody keeps their income as is. Obviously, that’s an expensive proposition. I’ve actually been costing it out.

Congresswoman Jayapal asked me to. And if this were to go on for just a matter of three, four months, we’re looking at upwards of three trillion dollars. So that’s already there are twelve percent of GDP. But that’s that. I mean, if you want a stabilization program that is going to be reasonably equitable, that is going to be effective. That is not going to face bureaucratic obstacles, such as what’s happening now with unemployment insurance, because with unemployment insurance, they did pass generous provisions for four months.

But you have to get it. You have to get the money. You have to apply. And the unemployment bureaucracy is used to having 200,000 people applying in a week. And now it’s five or six million people applying in a week. So that alone is preventing people from getting the money they need just to keep going.

Paul Jay: So Biden claimed when he would did his webcam with Bernie Sanders when Sanders announced his endorsement. Biden says he wants to have the most progressive administration since Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

You’ve written, there’ll be no recovery from the consequences of global warming. And I would assume you would now add the economic crisis now and post Covid-19, unless we succeed in advancing a global Green New Deal. So what for? If this Biden presidency is in the most optimistic way, and I don’t know if it’s realistic or not, but let’s see what would that administration have to do to A)Live up to the scale of the crisis and B) What he’s claiming he wants to be. And I share everyone’s scepticism about Joe Biden. But what would it look like?

Robert Pollin: Yeah, well, I I’ll just preface that by saying I also share scepticism. I can’t claim to be a fan of Joe Biden. But, you know, historical circumstances force people to go in directions that nobody would have anticipated. I mean, as our friend Noam Chomsky frequently says, the last progressive U.S. president was Richard Nixon. And that certainly wasn’t something that people would have expected of Nixon at the time. Nor would people have at the time said this guy is progressive because he wasn’t for the historical moment. He was reflecting a much more progressive overall political configuration. And so if there is a strong enough movement, left movement that forces the Washington establishment to the left in order to survive, then Joe Biden will move with that. He will have to.

So, you know, the crisis now is so severe there is going to have to be innovations across the board. Certainly what one of the obvious things we now recognize is that the US government, not all governments, but the US government, has basically unlimited financial capacity to spend as needed to accomplish important things. So if we come out of this crisis, and we say, well, we not only need the backstop of just funding to keep businesses and workers alive, but we need a long term strategy for growth and sustainability and a viable recovery. Well, the Green New Deal is the obvious answer.

People define the Green New Deal in different ways. But basically, it is, you know, massive investments in building a clean energy economy is the cornerstone, and having the fossil fuel industry wind down to zero over the next couple decades. And then we have to defend the well-being of the workers and communities that are dependent right now on the fossil fuel industry. You know, if we do that. That can be a foundation for a long term recovery and the transition to a sustainable economy that will stabilize the climate.

Paul Jay: So develop a little bit more concretely what the steps would be. You know, this is, you know, in the inconceivable moment where Bob Pollin’s asked to advise the Biden administration, but who the hell knows? We are in Inconceivable times. What are the steps you would advise, or you might be able to advise his advisers? How do you what are the practical steps that this administration will take, even in the most minimalist, both in terms of dealing with the deep unemployment and the and the global catastrophe, not just American and at the same time developing a Green New Deal?

Well, you know, implausible things do happen. I actually was an adviser in the Obama administration. And I mean, more implausibly, I wrote a paper which I guess, you know, nowadays we would call an outline for a Green New Deal in 2008 that basically became the green feature of the 2009 stimulus program. They basically lifted it out of my paper. So I thought that was a pretty good program since I drafted it. You know, it didn’t accomplish all that we wanted, but it wasn’t too bad. And we need something much more aggressive now because this is now a decade later and the climate crisis is worse.

Paul Jay: Look, just before you go further, let me just ask one economic question here. Is there any limit to how much money the American government can borrow? And like, obviously, there’s going to be the argument. Well, the American government just borrowed essentially four or five trillion dollars. Whatever this ends up being during this phase. You know a Green New Deal would be a whole another trillions. Is there any limit to how much the government can borrow?

Robert Pollin: Yes. But, well, let me first say the U.S. is in a unique position. You know, there is this school of thought called Modern Money Theory, which argues that all governments can borrow as much as they want to achieve full employment. I don’t agree with that.

Other countries are much more constrained. The reason the US is not so constrained is because the U.S. dollar remains the global currency of international trade. About 80 percent of global trade is done with dollars. So everybody needs dollars. And, therefore, the U.S. can take advantage of that. And everybody needs dollars. So on top of that, in a crisis, however bad things are in the U.S., they’re worse elsewhere. And so that there is a huge demand for U.S. government bonds. Normally for other countries, even in Europe, if other countries start borrowing and start putting out bonds at anything close to the rate we’ve been doing here in the U.S. Well, the interest rate on the bond is going to go up because people will see those bonds of Italy or Greece as being more risky because the government is borrowing. Government is borrowing more, which means it makes it more difficult for them to pay back. So that a lender will want a higher interest.

Well, the interest rate right now on a U.S. government bond, five year Treasury bond, is zero point four percent. Again, it’s like we’ll take this for nothing just to have a U.S. government bond because we know the U.S. government isn’t going to go out of business. So the U.S. government has this unique capacity at this point of almost unlimited ability to borrow. Now, the only thing that would weaken that is if we really get into such a severe crisis that something like a hyperinflation occurs. A hyperinflation could occur.

I would say it’s very unlikely. A hyperinflation could occur if the government borrowing increases, let’s say, five, six fold and the economy is still isn’t recovering. And then we really do have this ultra-extreme situation, that kind of thing that Milton Friedman talked about, which he described as a normal situation, but where you just have money pouring out, and you don’t have any goods and services being produced. So then that creates a hyper-inflation. Under that circumstance. Yeah. That U.S. government’s the confidence in the dollar would collapse.

Paul Jay: Can I can I just make sure I’m understanding that. Is that what would happen that if the American economy is so stagnant, so depressed, such high unemployment and so much money has been borrowed, that it reaches a point where instead of paying less than a percent, the amount of interest the American government has to start paying starts going up and up. And that becomes inflationary? Am I understanding that?

Robert Pollin: Let’s say it could. It doesn’t necessarily have to be. But that , in my view, let’s say, you know, over the next whatever, 18 months, two years would be the only scenario in which we could see any limitation on the U.S. government borrowing. A yes, is that ultra-stagflation? Yeah. Now, the stagflation that occurred in the 1970s resulted from oil prices going up six fold. That, obviously, is not going to happen now.

And by the way, if we transition out of oil and into green energy, we will be able to ensure that the prices are going to be stable. So that would take away the prospect of any kind of oil shock derived stagflation.

Paul Jay: If we reach a point where people, investors, the elites of the world actually find that even borrowing American T bills they don’t consider safe anymore and start to withdraw from that. Is there an alternative? I mean, is that just become such a shit show that the whole system starts to unravel?

Robert Pollin: Yeah. So if we’re at the point at which people, investors don’t trust American treasuries, then, yes, we are in such a deep crisis. And, you know, the level of uncertainty is so high. I mean, sure, one could say, well, look, China is a stronger economy, but China is obviously not so strong right now. You know, the IMF itself is predicting China will continue to grow, but it basically zero point one or one percent, you know. So that is a collapse from their growth trajectory, which has been for 40 years, eight percent, eight, nine percent. Say, , oh, well, the Chinese yuan is a viable alternative to the dollar. Yes. Is really projecting something that seems implausible at this point.

Paul Jay: There’d have to be a radical change in the Chinese peoples’ ability to consume because China is so dependent on the American market, and if the American market is screwed, what can China do then?

Robert Pollin: Yeah. And the global supply chains from which China is like the foundation. Who knows where, the you know, those are flat on their back, also? So to say that, you know, we have a clear alternative to U.S. dollars and U.S. Treasuries via China, to me just seems a really like an unlikely scenario over the next two years. So if investors don’t want dollars and they don’t want U.S. Treasuries, I have no idea. They won’t want oil. So gold. You know what? Gold doesn’t do you any good. You can’t eat the gold. So I really don’t know what the world would look like. And, you know, for looking at a two year scenario in which investors say we just we can’t take any more dollars.

Paul Jay: Has capitalism exhausted itself? I mean, everyone thought it would eventually and of course, it’s being predicted over and over again over the decades. But have we actually reached a point where it has, and/ or looking at some kind of either, some in certain places of the world, at least. I don’t know if it could be done in the United States, but a radical transformation toward some form of socialism and/or some form of Dark Ages

Robert Pollin: Yeah, I mean, capitalism as we know it, I think well, it already had exhausted itself because we were already at a transition out of neo liberalism. I mean the global emergence of neo fascism. You know, Trump obviously is the most obvious example, but both Bolsanaro in Brazil, or Orban in Hungary and Netanyahu in Israel.

We have, you know, a huge movement out of, away from neo-liberalism because neo liberalism didn’t deliver well-being for middle class, working class people. Unfortunately, the response has been primarily neo-fascism and neo-fascism was able to incorporate racism and anti-immigration attacks at their core, so that you could blame, you could kick down, instead of kicking up, and the left agenda of attacking capitalism and building some egalitarian alternative hasn’t really taken off.

But I think this is a moment where it can. And so the critical thing, I think, for us is to define what we mean when we say we have an alternative that’s viable, that people can believe in. I think, you know, for all its flaws, I think the Bernie Sanders campaign did a great job in raising these issues and defining what an alternative to neo liberalism and neo fascism could be. So I think that’s on the table. Corbyn did reasonably well on that also. So we just have to push it to the point at which these things become hegemonic to the point at which they become dominant political forces. We’re not there yet. But I think there’s movement in that direction.

Paul Jay: You raise the issue of the nationalization of the fossil fuel industry as a really necessary component of developing an effective Green New Deal. I’d add to that now. I think you would too. The nationalization of certain sections of the banking industry. As long as finance is controlled by who it is controlled by, and these days, it’s so concentrated ownership into a few asset manager funds like BlackRock and Vanguard and State Street that control Goldman Sachs and the other places. But on the whole, finance. There’s a quote from Roosevelt about when private interests dominate government, are stronger than government. It’s essentially the definition of fascism. Well, we’re definitely in a situation where corporate interests, private interests, but specifically banking interests, controlled government. It seems to me if there isn’t both nationalization of fossil fuel and at least a section of the banking industry, which without all this public subsidy would be down the toilet. One the government could buy doesn’t have to, just out and out nationalize. It could simply buy sections, enough sectors of the banking industry to have an effective public interest banking system. Is there any other way other than that?

Robert Pollin: Well, yes. I mean, I think we have to realize that that Wall Street would have collapsed 12 years ago if they hadn’t been bailed out. So Wall Street only exists on the foundation of public subsidies. You know, the bailout in 2007, 2009 added up to about twelve trillion dollars. So that was, for the time, that was over, let’s say, 60 percent of U.S. GDP. And the bailouts on Wall Street dwarfed the tiny little eight hundred billion dollar stimulus program that Obama passed in 2009.

So now here we are back again, you know, 12 years later, only 12 years later. And the bailout that was undertaken during the Great Recession is now also now going to look puny relative to what Wall Street is going to get from the Fed. So really, without Fed bailouts, we would have no financial system operating whatsoever now. So, yes, certainly it is clear that maybe we let some of these institutions fail, or the government just takes them over. And then at that point, we start to define what a financial system, banking institutions could look like that operate under some kind of public well-being criteria, as opposed to squeezing every penny of profit out of working people in this economy. So, yes, we are—-

Paul Jay: Here’s another quote from Roosevelt. This is another 1938. “The justification of private profit is private risk. We cannot safely make America safe for the businessmen who does not want to take the burden and risks of being a businessman.”

Robert Pollin: Right. Exactly. So these big Wall Street firms and big corporations have been pampered under neoliberalism, and to getting socialism for themselves. So the government that we the people assume their risks and they keep all their profits. And that’s the system that they have. And that’s a system that they like. And sure. Why wouldn’t they like it? So but, you know, as Roosevelt quote, you have there perfectly captures it. If these businesses literally cannot operate without a foundation of government bailouts, then they shouldn’t exist. If they’re going to exist as private entities, they have to be private entities that accepts some standards of social responsibility. Major, not just rhetoric, but in actual practice, they have to be committed to some standards of social well-being because they are beneficiaries of the public interventions. And the fact that they won’t means that they need to be nationalized, at least some significant share of them.

Paul Jay: OK, so now put on your imagination hat. So just imagine there is a really progressive, mass movement, very conscious, national assuming people can get into the streets that can rally hundreds of thousands, even millions of people in the streets in support of a progressive agenda. This progressive movement has just elected progressives that now control Congress and have a progressive president facing, of course, big enemies, both in finance, military-industrial complex and so on. So it’s not some la-di-da utopia here. But I mean, even what I just described is a little la-di-da. But whatever. What would that progressive government do? So to boil it down—if there was a federal government, then you can apply this to states and cities. And maybe what I’m saying is actually more possible in states and cities than federally, at least to begin with. And what does this progressive government do if, for example, in this situation? We’ve talked about nationalizing fossil fuel sections of finance. What else does it do?

Robert Pollin: Well, we definitely nationalize the health insurance industry. So, yes. We have a Medicare for all. And by the way, Congresswoman Jayapal also has an excellent bill that would extend Medicare, existing Medicare to anyone who’s experienced unemployment. So that could be a stepping stone to Medicare for all. So, if we have a health insurance system that covers everybody decently, we have a Green New Deal Foundation, which is transforming the energy economy. Also agriculture.

And then we, on that foundation, we can also operate, according to the nineteen forty six version of the Full Employment Act, which is, you actually guarantee jobs for everybody, at decent pay. So I think that’s a pretty good foundation. We will have gotten rid of the fossil fuel industry that has to go anyway. We will have a transition for everybody who is negatively affected by the demise of the fossil fuel industry. We have something that can do a full employment economy with a decent wage standard. And we have a global, global Green New Deal, I should say, that is going to save the planet. That’s going to eliminate the threat of climate change.

Paul Jay: And I’d add to that a couple of things. One, from what you described earlier, what’s happening in Africa. But it’s going to be happening in parts of Asia and Latin America. There’s going to have to be a massive bailout of huge sections of Asia and Africa and Latin America. Are they? Or this is going to become a catastrophe on a scale never heard of.

Robert Pollin: That’s right. So, you know, the US has been the stingiest high income country in terms of foreign assistance. So we give zero point two percent of GDP. So that’s 40 billion dollars for foreign aid. So countries like Sweden and Norway give up five times more as a share of GDP. One percent. But even one percent is nothing at the very least during this pandemic, what we really need is the U.S. government to be giving something like a trillion.

It’s the only way. I mean, if we really are seriously, if the WHO is anywhere close to accurate and saying there’s going to be 10 million infections in Africa. And as you said, let’s double that number for low income economies of Asia and Latin America. So that would be conservative. So 20 million people in poor countries that have very fragile public health infrastructures. This could be, you know. Let’s go back to the Black Death, the plague of 1350. We could be looking at something like that. And let’s say we don’t even care about any of those people. We couldn’t give a damn. But, of course, what if we have 20 million people infected in poor countries? Of course, the virus is going to come back to the US. Yeah. So we need an intervention on that scale. We need a… I mean, we just did two trillion in the U.S. through the Treasury and untold trillions more through the Fed.

So we need a trillion coming out of the US. And another trillion coming out of the rest of the high income countries to at least provide some decent stabilization of health care systems in the low income economies. That would be a low number, I think. But we need that and we can argue for it on strictly, absolutely selfish grounds that we have to control Covid19.

Paul Jay: Add two things to that. One, it’s not like there’s not enough wealth to do that. It’s not just about borrowing. Jeff Bezos could throw in practically a trillion all by himself. Right. So it’s not about just necessarily endless borrowing. There is such a thing called taxation. And the other thing just to remind people, because I’m sure people listening to this know what I’m about to say, but why is it Africa has no decent health care system?

Because, you know, from World War II on, the natural development of even modern capitalist and certainly socialist economies in Africa, were all undermined, destroyed. And leaders were murdered. And in Latin America, dictator after dictator supported by U.S. foreign policy, that led to the undermining of natural development, even capitalist development in Latin America. So it’s not like United States and Europe too, to some extent, aren’t responsible for these places being so vulnerable.

Robert Pollin: Of course, you know, there’s no question about it. I mean, having done some work, policy work, in both Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa and trying to introduce some egalitarian programs and then connecting with progressive movements there.

Paul Jay: Yeah, I mean, you’re facing massive obstacles that have been built up for decades through the undermining of any kind of progressive movements, progressive politics by imperialist powers, starting with the United States. The danger of war in moments like this, it seems to me, is very high, not just through kind of normal competition between these days, it will be China and the United States. It could be Russia, but it’s a very aggressive, militarist government in power right now. As sceptical as we are about Biden, Trump, I believe and I think you do, too, represents a kind of not just authoritarianism, but a real potential fascism surrounded by the worst, most right wing elements of the oligarchy, allied with, you know, very backward sections of the society. And it’s very, very dangerous moment in many ways, but not the least of which the threat of war. And you have Steve Bannon, who still apparently in Trump’s ear, openly advocating a military confrontation in the South China Sea. You have Trump and some other people in the Pentagon and other people actually seriously talking about the possible use of tactical nuclear weapons.

And, of course, Iran, where Trump, the Trump administration, has been very dedicated to bringing down the government of Iran. And now with Iran in such terrible shape as a result of sanctions, Covid 19 and the mismanagement of the economy by the Iranian government. But I think that pales in significance to what the first two factors are responsible for.

Robert Pollin: It’s very, very dangerous.

Paul Jay: So it seems to me that whenever we’re talking about the Green New Deal and we’re talking about what needs to be done, we have to also talk about the danger of the nuclear weapons industry and nuclear strategy, the size of the Pentagon budget, and not that there isn’t enough money to pay for all that and do the other stuff. A point you’ve made. But just the inherent danger of all of that. The threat of war obviously is increased, as you mentioned, as we mentioned, a bit ago, the pressures for migration are going to become severe. Again, if we talk about 10 million infections in Africa and comparable problems, chronic catastrophic circumstances in, say, the Caribbean and Central America. People are going to want to get out of there, however, and that is going to create pressures for Trump, who’s going to love this stuff! Who’s going to want to blame everything on immigrants, foreigners? So the opportunity to start a war and deflect attention from his own failures is going to be close to irresistible.

And obviously, Iran is a is a is a big target. Always has been. I mean, Trump has to date has resisted the most militaristic advice he’s been given on Iran. But how long is he going to resist if it really gets to the point at which he thinks he’s going to lose the election unless he can change the story? If there’s a story out there in the media is that Trump has screwed up the management of the Covid19 19 crises, which is a story that is increasingly becoming obvious. But if that story really sticks and he thinks he can’t reverse it through his usual kinds of rhetorical somersaults, sure he’s going to want to start a war. And so that is a yes, that’s a real threat. And we have to be really totally on guard around that.

Paul Jay: All right. Well, thanks very much for joining us, Bob.

Robert Pollin: Great to do this. And I really wish you all the best with this venture. Thank you

Paul Jay: And thank you very much for joining us on theAnalysis.news podcast.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Robert Pollin is an American economist and professor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he is also founding co-director of its Political Economy Research Institute. Pollen received his PhD in economics from the New School for Social Research in 1982.

wonderful issues altogether, you simply gained a new reader.

What may you recommend about your post that you just made some

days ago? Any certain?