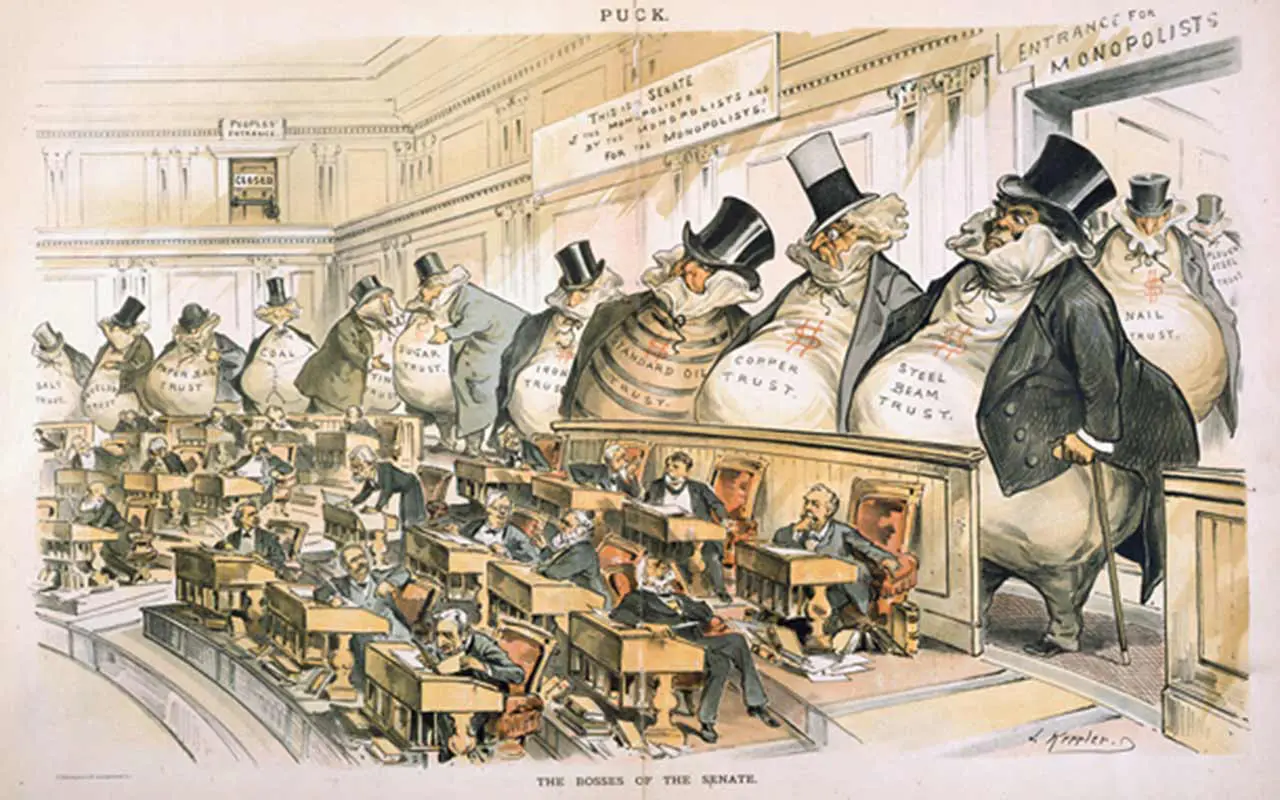

The Bosses of the Senate

To reduce inequality, monopolies in finance and other economic sectors should be broken up or made public, says Polly Cleveland on theAnalysis.news podcast with Paul Jay.

Paul Jay

Hi, I’m Paul Jay. Welcome to theAnalysis.news podcast, and please don’t forget there’s a $10,000 matching grant challenge. That’s one of these things where one of our supporters has put up ten thousand bucks, and for every dollar that’s donated between now and the end of the year, he’ll kick in another dollar, up to ten thousand bucks. If you have a current monthly subscription, well, first of all, thank you, but if you increase the subscription, he’ll take that whole amount times twelve and match that. If you don’t have a monthly subscription and you sign up for one, well, same thing: times twelve, matching that. So, you’re going to help us raise another ten grand really rather quickly if you contribute now. Thanks for joining us, and we’ll be back in just a few seconds.

There’s a lot of talk these days about the tech monopolies: Apple, Google, Microsoft, Facebook and Twitter. The Senate recently issued a report and grilled tech leaders who are assailed from all sides for having too much control over the flow of information. Most modern capitalist countries have some sort of anti-trust legislation recognizing that private monopolies in any sector of the economy inhibits competition and creates concentrated wealth and political power.

Even most capitalists in the end think completely unregulated and unrestrained monopolies are not good for capitalism. First, one sector of the elites can become so powerful they essentially take over the government. [Franklin] Roosevelt said this was the very definition of fascism. Such monopolization also makes workers and consumers — who are actually mostly the same people although they’re often talked about as if they’re not — subject to lower wages and higher prices. This is also not good for capitalism as a system even though it might be good for some individual capitalists as it lowers demand for products and tends to make recessions longer and more frequent.

There are various approaches to what to do about the current state of monopolization. While tech gets most of the public attention, I think an even more dangerous concentration of wealth is in the finance sector, which to a large degree owns much of big tech. I’ve written an article about BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street asset managers who together control more than $14 trillion dollars under their control. That’s more than the GDP of China. Institutional investors like these Big Three have effective control of voting stock across 90 percent of the S&P 500 and beyond. While they don’t control these companies on a day-to-day basis, to a large extent they get to choose who does. The other major banks wield enormous power in every sector of the economy. And while Roosevelt said that it was the banks that were behind the monopolies, ownership has only become more concentrated since his day.

So, what should be done with the monopolies?

Some say, break them up. Some say, regulate them. Some say, create publicly owned banks and other enterprises that compete with the privately-owned ones, regulate private monopolies in the public interest when they exist in critical sections of the economy. Roosevelt advocated that, too.

Now joining us to discuss this, and hopefully from this point on to monopolize the conversation, is Mary Cleveland — she’s known as Polly Cleveland. She’s an economist focusing on wealth distribution and a longtime activist for social justice. Her blog Econamici also appears on Dollars and Sense website, and she serves on the Dollars and Sense board. She’s an adjunct Senior Research Scholar at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs. Thanks so much for joining us, Polly.

Polly Cleveland

You’re welcome. I’m delighted. And you’re a terrific interviewer.

Paul Jay

Thanks. [Laughs.] You just say that because I’m about to interview you —

Polly Cleveland

Of course!

Paul Jay

— and you want this to be softball. I’ll have to give you a hard time now.

OK, so start with some history. The Sherman Act in the late 19th century was the big, founding anti-trust legislation in the United States, and apparently passed on almost unanimously in the Senate at that time. So, talk about the conditions that gave rise to the Sherman Act — and has it been effective? When we look around the United States, it doesn’t look like it was so effective: there are monopolies everywhere you look.

Polly Cleveland

Well, there’s a long history. Now, back in the 19th century, there was the railroad monopoly and the steel monopoly, all kind of allied with each other. Among other things, they were ripping off the farmers who relied on the railroads to ship their goods to market. You interviewed Thomas Frank about the populist movement, which was a big organized movement of farmers — and to some extent small business, but largely farmers — that led to a great deal of outcry and eventually the 1890 Sherman Anti-trust Act, which at first was not terribly well enforced. In fact, at one point it was used against labor unions.

Then there was the Clayton Act in — and I don’t have the number in front of me around 1910 or so [1914]. And then with [Teddy] Roosevelt, there were various strengthenings of anti-trust. Well, there was a little bit under Teddy Roosevelt, but then the real vigorous anti-trust actions came with Franklin Roosevelt. And that also included the Robinson-Patman Act requiring businesses to charge the same price either to different customers or different vendors. That led to what were known as the fair-trade laws, which kind of put out of business A&P and some of the other great chains. Well, it reduced their power. So, there was a tremendous amount of anti-monopoly agitation, a lot of litigation, and you had a period starting with certainly with the Roosevelt administration and running up to about the 1970s in which there was, in fact, very vigorous anti-trust enforcement by the Justice Department.

It was also a time, and this is out of my research, of growing equality. In the mid-seventies, equality reached its highest point or inequality reached its lowest point in the history of the US. I would attribute that to two things: very vigorous anti-trust enforcement and also, with World War II, very high marginal tax rates that had a great equalizing effect. It really wasn’t until the Kennedy administration that you started getting cuts in those high marginal tax rates.

I argue that equality is good for the economy. It produces more jobs, it produces more output. It produces, you know, general growth. (And growth doesn’t have to be bad. But that’s another subject.) But in any case, that era of anti-trust was, I think, very effective.

The problem was in the 1970s, and this is where I stepped into the picture. My ex-husband and I were working for Ralph Nader, and Nader did some wonderful things for consumer protection. But he did begin to play into the narrative of the old monopolists, which is, big monopolies are efficient; they deliver lower consumer prices; and this is what counts. Therefore, you shouldn’t have regulations against monopolies because you’re denying consumers the benefit of low prices.

By the time I was in graduate school in economics at Berkeley, this certainly was what you were seeing in the textbooks. Monopoly was kind of relegated to a few chapters at the end of the textbook, if you even got to it. And the whole thing was, well, you know, monopolies will behave themselves; they’re afraid of competition; so, they’ll be good. These monopolies are giving us low prices and that’s what counts. Besides, they’re so big and glittering and efficient. This was also the era of John Kenneth Galbraith’s The New Industrial State. All these big beautiful corporations that were transforming the world.

So, it wasn’t just the bad guys at the University of Chicago. It was also a lot of good liberals who saw big corporations as sort of the new, modern wave of the future. At Yale University in the mid-seventies, there was Robert Bork, who was also famous for the Saturday Night Massacre and not quite making it to the Supreme Court. But, in any case, he produced a very important or influential book called, I think, The Monopoly Paradox. I’ve forgotten what the exact title was [The Anti-trust Paradox, 1978], but it made the same argument: monopolies were efficient, they were beneficial, and by regulating them, you were denying benefits to consumers. That was influential not just on the right wing and the University of Chicago, but it was influential on the left wing, too.

Robert Posner published several books and articles arguing that lawyers and judges should pay attention to cost-benefit analysis. That is, rather than just saying what was fair or what was legal or what was according to precedent, they should weigh the costs and the benefits. And of course, when this came down to anti-trust, well, they had to look at the benefit to consumers of low prices and weigh that against what had previously been considered as fair.

Those were all the influences coming to bear when my husband and I were working for Ralph Nader. I worked on a project for the Department of Agriculture, and the story there was that the big businesses were harming consumers with pesticides and they were harming farmers. So, we went to California and we did a report on how the large landowners were getting all sorts of special favors from both state and federal government. This was all good work. A lot of Nader’s work was very good, but it had the effect of further undermining confidence in government regulation.

We start with the Reagan administration in 1980 and saw a gradual — or not just gradual — decline in anti-trust enforcement. They dropped some cases. They let some other folks off with small fines. And then you get Bill Clinton. The Clinton administration went right along with this: not enforcing anti-trust, small slap-on-the-wrist fines. It was Bill Clinton who allowed the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, which had previously required investment banks to keep their money separate from the money of depositors. So, all of a sudden you had investment banks could now dip into their deposits to make speculative ventures, which is what they started to do. Also, at some point in there, the rule was dropped prohibiting branch banking. Previously, US banks stayed somewhat small, or at least most of them, because they were restricted to operating within one state. I forget; I think that happened under Clinton. [The Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994.] In any case, with the repeal of the laws against branch banking, you got this mushrooming of banks. And as you mentioned in your introduction, the banks came to take over more and more of the economy. And the economy became more and more unequal.

Then, of course, you had the financial crisis of 2008. I saw that coming because I’m a land economist and I could see the price of land taking off. It was the price of housing but that’s the price of the land underneath. It was taking off the way I knew as a historian that it had in the 1920s. In the 1920s, there was a great bubble of bank lending and a tremendous amount of speculation, not only on stocks, but on land. This was partly a consequence of the invention of the automobile, which suddenly opened up a lot of suburban land to development. You had these scam subdivisions in which a developer buys a farm, builds a lake and a clubhouse, and he sells off lots to average people who are told, “Oh, my God, look how fast this land value increased. If you buy this little plot and pay for it on time, pretty soon you’re going to be rich.” They were doing speculative lots like this in Florida, you know, underwater lots. [NB: Literally submerged in actual water — as in, swampland — not “underwater” in the financial sense.] And banks were behind all of this lending to the speculative developers. The result was: bubbles come to an end. The people who had bought these speculative lots stopped paying on time; the developers stopped paying the bank loans; and the banks started running out of money. By the time the stock market crashed in 1929, a lot of the banks were underwater [in the financial sense] with these real estate loans. It was really more the real estate bubble that pulled under the banks as the Roosevelt administration began in ’32.

Come 2008, I saw this coming again because I saw the huge bubble in real estate values. And that was around the world, too — in the UK, Spain, everywhere. There was just this bank-financed bubble and it was going to go bust. The only thing that surprised me was that it didn’t go bust sooner. I mean, I was seeing this bubble taking off by 2004. It was a miracle that those banks held up until 2008.

Then, of course, you know, the incoming Obama administration bailed out the banks and let millions of homeowners who had paid these overpriced mortgages lose their homes and go bankrupt. It was just an incredibly bad move. You wonder where Trump gets his support? He gets his support from small homeowners in small towns, rural areas, who really got the worst of this real estate bubble. It was clear the Obama administration supported the big banks. In fact, part of the response to the burst of the bubble in 2008/2009 was to merge more banks. To make them bigger. You talked about the banks in your introduction. These are some of the worst offenders.

Paul Jay

Let’s go back to something you said earlier, which is the basic question here. The development of monopolies under capitalism seems inevitable and spontaneous. Big fish eat little fish, and if left alone, market forces on their own will almost always give rise to big monopolies. So far, the best anti-trust legislation and regulation has been able to do has been to create a few very big monopolies that somewhat compete. While the market is still monopolized, it’s by two or three companies per sector, but it still winds up being the same kind of power and concentrated wealth.

Now, one of the people that said that this was both inevitable and a good thing in a way was Karl Marx. He said that you can’t really do much about this. I don’t think he was against anti-trust legislation. Most of it came after he died, anyway. But I would argue that he would argue, fine, try to regulate them. But what the big monopolies are really doing is showing that they can be brilliantly organized internally. Amazon, to me, is, what’s the word? Magic? How brilliantly is that enormous company internally organized?

But Marx argued that the overall economy is complete anarchy so you keep seeing periodic crises. Now we’re seeing that it’s such anarchy that they can’t deal with the pandemic. They can’t deal with climate. Even though many of these companies, including the banks, are just unbelievable on how well they’ve digitized and how well they plan internally.

So, you’re left with few things to do here. First, in terms of banks and even the tech sector, some people are saying we should regulate these things as if they were public utilities. (I guess they still stay in private hands in that kind of scenario?) Second, at least in critical sections of the economy, you literally either buy monopolies out and make them public or create a public one. But I think it’s a lot easier to buy one than create one from scratch, and in times of crisis, a lot of these things could be bought pretty cheaply. Or, third, you have to try to have a more vigorous enforcement of anti-trust legislation.

But that’s always a problem because the politics is so controlled by these guys. There’s a cartoon I’m going to put up from the late 19th century. It’s a bunch of big monopolists standing with bloated, money-filled bellies behind senators sitting in Congress. And that’s very much the problem. The Department of Justice’s vigorous pursuit of the execution of anti-trust legislation depends on who’s in power. Increasingly, those in power are people more and more beholden to one sector of finance and monopolists or the other. I mean, of course, that’s a conundrum, whatever you try to do. But I guess what we’re saying is if you had a progressive government — and you’d need a people’s movement, too, to do any of this. I don’t know if the Biden administration is going to get serious about anything anti-trust. The Obama administration made a few moves in that direction, but certainly not in any serious way.

What’s your take on this? First, what’s politically possible with this Biden administration coming in? And if there were a really progressive Congress and president, then what should they do?

Polly Cleveland

Wow, you covered a lot of ground. You mentioned Marx. This was the big disagreement between Marx and the other great leader in the populist era, the American Henry George. Marx thought concentration was inevitable. Somehow you have to get the people on top of it to control it, eventually. George and his followers — and that includes the populists who got their economics from George — recommended breaking up the monopolies everywhere by taxing and regulating them. That’s a complicated story. You need to interview Richard R. John at the Columbia Journalism School, who’s an expert on all of that.

But the anti-trust of the Roosevelt administration was very successful. It is possible to have really successful anti-trust administration. You just have to look at how well the economy did in that postwar period when inequality was way reduced. In other words, it is not inevitable that the banks and the big monopolists will control everything. You know, if you think it is, then you’re sort of giving up beforehand. There have been anti-trust successes in the past. The labor movement used to be very powerful. The liberal backsliding from the 80s on allowed the big corporations to undermine the labor movement. Bill Clinton is as guilty as any in that regard.

But I wouldn’t give up. Yes, you need a populist movement. And you know what, I am excited these days that all of a sudden there’s a big focus on monopoly. Partly it’s because Big Tech has scared the Republicans now as well as the Democrats. I mean, it’s the Senate now that’s proposing to investigate Big Tech. Of course, they say, “Oh, well, you know, they’re liberal, they’re prejudiced against us Republicans.” Well, maybe they are, but maybe you need a whole bunch more of them, smaller ones rather than big ones. So, I’m at least a little bit hopeful that as people become aware of the damage that that monopoly does, both through monopolistic practices, but also causing this enormous degree of inequality in this country. I mean, almost every problem you look at traces back to extreme inequality.

Paul Jay

Well, yes, sort of. I mean, I agree this issue of nationalizing big monopolies or creating from scratch public alternatives to privately-owned monopolies is a bigger conversation. We’re not going to see that under the Biden administration. I don’t think we’re going to see it without a mass movement at a higher level. I do think we need to talk about it a whole lot more because I think one of the things holding back a bigger mass movement is a vision for what could be.

I don’t mean a completely utopian vision. On this issue of publicly owned big enterprises, publicly owned banks and so on, we already see parts of it in Europe and Canada, even in the United States. I mean, there are lots of publicly owned things in the United States. But in terms of mixed economy, the publicly-owned is so much weaker and the privately-owned so much stronger that the class that owns the big privately-owned monopolies really holds the political power.

Anyway, let’s put that aside for now, because it’s a bigger-picture conversation. What would you like to see this incoming Biden administration do? What’s the best-case scenario that one could expect? I don’t think Biden has any great record on this. The people he’s starting to appoint in many departments and transition teams aren’t very encouraging, although Gary Gensler is actually not a bad appointment. He was at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission in Chicago, and if I understand it correctly, they did try to regulate how much of any individual commodity any individual could control. They lost that fight, more or less, in the courts, but Gensler did seem to fight for it. So, at least on that question, that seems like something encouraging. What do you want to see them do?

Polly Cleveland

Well, let me first respond to something you said earlier, that these big banks are very efficient. The answer is no. They are terribly inefficient. They are terribly managed. I mean, I’ve talked about it with people who worked for them. But they make so much money from their monopoly position that, at least until they need to be bailed out again by the government, they are hanging on due to their monopoly position. But a little bit of an anti-trust nudge and some of them might just fall apart. And they’re crooked, for God’s sakes, you know?

Paul Jay

Well, they’re very efficient in their crookedness, anyway.

Polly Cleveland

Yeah, they are good at bribing people and influencing people. But, you know, why is Jamie Dimon still the head of Chase with all of these indictments and criminal behavior? I mean, um, what? [Laughter.] So, to some extent, I think the big banks — Citibank is a joke. You should talk to some of the people who have worked for Citibank.

Paul Jay

Amazon is pretty well organized.

Polly Cleveland

Amazon appears to be pretty well-organized as an absolutely ruthless monopolist in the way it sucks the juices out of its vendors. It’s very nice to high-income consumers like me. I suppose we’re supposed to be mollified by that. But what it does to its vendors…

But it’s a new company. You know, General Motors, once upon a time, was very efficient. When you’ve got a new company set up under some brilliant people, you know, for a while, they may be very well-managed and very efficient, but it doesn’t last. I mean, General Motors fell apart. Businesses that have been around for a while pass on to the next generation of managers and they get fat and happy and sloppy and incompetent. And it’s inevitable.

Paul Jay

But the argument against breaking up either the banks or even Amazon or the tech companies is also that it only works for a while. Even if you can accomplish it, which is very difficult because they have such powerful lobbying, the capital that’s actually owns those things is very concentrated. And they’ll figure out a way to bring it back to scale. Like, they broke up the telecoms but it’s more or less back to a few big monopolies in telecom. Just breaking them up doesn’t last very long in terms of weakening them politically or economically.

Polly Cleveland

That’s a recipe for giving up. I mean, the fight never ends. You know, the anti-trust fight from the Roosevelt era was so successful that people forgot about the importance of anti-trust. So, eternal vigilance is the price of freedom. You’ve got to keep fighting. But it’s much easier to fight if you don’t have such an unequal economy with all of the wealth. It’s going to take a revolution like what happened during the Roosevelt administration. You know, more Pecora hearings, more people marching in the streets. And if the economy really collapses as badly as I think it’s going to collapse as a result of this virus, I mean, bad times sometimes bring on activism. Let’s hope. I mean, I’m going to keep fighting. And my daughter is politically very active and she’s going to keep fighting this. There’s no escape from fighting it. You have to keep fighting.

Paul Jay

Yeah, I sure wouldn’t argue against that. I would say that added to the demand of breaking up the big monopolies should be the creation of public companies at scale. So, I’m certainly not arguing against fighting. But be very specific, if you can. What demands would you make of the Biden administration in this area of anti-trust?

Polly Cleveland

Postal banking. You can have the so-called Tobin tax, a small tax on the stocks and bonds as they are turned over, which would stop a lot of the corrupt behavior regarding the securities of the banks. Yes, investigate the banks and break them up, if you can. As I said, you do need public banking, starting with postal banking. It would be nice if you could go back to limiting the banks to certain states. You know, your bank, TD — Toronto-Dominion — is one of the big banks, but it’s very small compared to Chase. You don’t need anything as big as Chase and Citibank. So, yes —

Paul Jay

That sure ain’t my bank. I don’t own it. [Laughing.] You’re saying that because I’m partly Canadian.

Polly Cleveland

Well, yeah.

Paul Jay

I’m a dual citizen, although you accused me of saying “a-boot” [instead of pronouncing it, “a-bowt”], and I don’t think I ever say “a-boot.” But anyway. [Laughter.]

What would you do with the tech companies?

Polly Cleveland

There are a lot of interesting solutions. Certainly, you want to break them up. They are violating — just enforce the anti-trust rules. You don’t even have to have new anti-trust laws. They are doing tied sales, they are ripping off their suppliers, playing them off against each other. They are potentially ripping off consumers. They are violating anti-trust laws, up, down and crosswise. Just enforce the law. And I think there is a lot of movement for that.

But, you know, you need some new laws, too. Exactly how you make something like Amazon more of a public market? The best markets always have been heavily regulated. So, you need a framework for Amazon so that it becomes like a public market where the vendors can go out and display their wares and people can buy them without 30, 40 percent going to Amazon. Maybe Amazon should be nationalized. I don’t think that would be a bad idea. I don’t think that’s going to happen.

Paul Jay

I think I actually think in some perfect world where you really have a progressive government and a progressive mass movement, I would think one of the most important things that could transform the economy is to buy Amazon. It doesn’t matter what it costs. And then, first of all, raise the minimum wage of Amazon to 25 bucks an hour, which would just transform the wage scale in the whole country.

Polly Cleveland

Yes, that I am certainly down with raising minimum wages substantially. I mean, $15 is a start. You know, the old economic view was, oh, my God, that will kill jobs. Well, yeah, raising the minimum wage would destroy jobs in a perfectly competitive economy. But we aren’t in anything close. And when you have a monopolized and monopsonized — that is, a single buyer as well as a single seller — when you have a monopsonized economy, raising the minimum wage is a very good way to fight back.

Paul Jay

I should add one thing, because every time I talk about this, I get emails. I agree with the emails but I don’t want to get too much into this now because it is another topic. But when I talk about creating a publicly-owned Amazon I’m not talking about a monopoly. Amazon could continue but you could create a public competitor. But also, I think it’s very important that the ownership of large, publicly-owned enterprises is diversified. Too much economic concentration, ownership, and power in too few hands is always going to be a problem, even if it’s public. So, this issue of how to create a diversified form of public ownership when you have things that are on a big scale needs to be addressed.

But that being said, at least a democratizing process can go along with public ownership. In the current situation, there’s simply no democracy involved in how Amazon does business.

So, concretely, what would you like to see a Biden administration do?

Polly Cleveland

When Biden takes office there are certain things he can do immediately without worrying about Congress. He can forgive student debt, which is billions already. He can fully finance the IRS. He can shift funds from elsewhere if need be. After all, if Trump can finance his war by shifting funds, Biden can fully fund the IRS.

Paul Jay

What does that mean, “fund the IRS”?

Polly Cleveland

Well, the Internal Revenue Service collects only a fraction of income taxes due because it has been increasingly and desperately underfunded over the years. Deliberately. And this has been to some extent a bipartisan decision. The result is that the IRS focuses on collecting taxes from the little guys and forgets about the big guys because it takes a lot of expensive staff and lawyers to go after major corporations. So, with full funding, there are literally billions of dollars that the IRS could be collecting without any change in the tax laws. So, that might pay off in a year or so.

Fully fund the anti-trust division of the Justice Department and start enforcing. A lot of what Big Tech is doing and the monopolies are doing is blatant violation of anti-trust — on its face, a violation. Wouldn’t be too difficult to prove.

Beyond that, Richard Vague and Michael Hudson and others have called for a debt jubilee. There need to be programs for mortgage debt relief; student debt relief — and not just federal; health care debt relief; small business debt relief. Reducing the load of debt is very important if the economy is to recover. Send money to cities — again, transferring it if necessary — because that saves many more jobs than other spending. I mean, not highways: you need to spend money on fixing cities and providing city services. And if you get ambitious, you can he can cancel new contracts for weapons systems or close foreign military bases. Again, a lot of that he can do absolutely on his own without requiring Congress to agree. You’ve interviewed Bob Pollin. He says that military spending provides the least employment per dollar spent of virtually any kind of federal money. So, that would give Biden plenty to do without having to have the Senate.

Paul Jay

So, a final word from you, Polly, on this whole question.

Polly Cleveland

A final word. Well, my final word is that I am very optimistic that this new generation of trustbusters — and I’m talking about Barry C. Lynn and Zephyr Teachout and so many others — are going to have a real impact. We’re going to see aggressive enforcement of anti-trust laws — as well as of taxes. I mean, we need taxes on folks like Amazon. In some cases, heavy taxes and tax enforcement will also help to break them up. It’s not just anti-trust laws. It’s also taxing their ill-gotten gains. So, I’m very optimistic. I have to be, and I’m going to keep fighting.

Paul Jay

Great. Thanks very much, Polly.

Polly Cleveland

OK, you’re welcome. Thank you.

Paul Jay

And thank you for joining us on theAnalysis.news podcast. And please don’t forget, there’s a matching-grant campaign going on here. One of our supporters has donated ten thousand bucks. So, if you create a new donation today, he’ll match it. If there’s a new monthly subscription, he’ll multiply that by twelve, and he’ll match that. And if you’re a current donor doing a monthly subscription and you raise the amount of the monthly subscription, then he’ll multiply that by twelve and match that up to the ten thousand bucks. So, please donate.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

This was really super, very informative, with great background on how we got here. Reminds me of Matt Stoller’s article several years ago: https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/10/how-democrats-killed-their-populist-soul/504710/