The Making of Norman Finkelstein – Reality Asserts Itself (pt 4/8)

This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced on January 4, 2015. Dr. Finkelstein explains why he endures slings and arrows, being isolated and attacked for his critique of Israel.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to Reality Asserts Itself on The Real News. I’m Paul Jay. We’re continuing our interview with Norman Finkelstein. So please join us again.

Hi, Norman.

NORMAN FINKELSTEIN, POLITICAL SCIENTIST, ACTIVIST, AND AUTHOR: Hi. I want to just–in deference to my past, I have to–.

JAY: Let me set it up first, ’cause, first of all, you’ve got to watch the earlier segments, ’cause the story Norman’s going to tell is not going to make any sense if you don’t. But for a while, as Norman said, he was a Maoist, and before we move on, he’s going to–he’s got a story he’s just got to get out.

FINKELSTEIN: Well, first of all, I want to show that my memory hasn’t gotten that bad. It was Yao Wenyuan, Wang Hongwen, Zhang Chunqiao, and Jiang Qing. Those were the Gang of Four.

JAY: ‘Cause in the previous segment,–

FINKELSTEIN: I couldn’t remember one of them.

JAY: –Norman only got three out of four. So he figured out the fourth here.

FINKELSTEIN: Yeah. I would have lost final jeopardy. So I want to show I do remember that.

The story was when I was–I had a high school sweetheart. Her name was Maxine. She’s actually an Israeli now. She moved there 30 years ago. We’d fight like cats and dogs, but old friends. And once we were walking along the beach in Rockaway, and I’m trying to convert her. I said, Maxine, now, you agree one plus one equal two. She says, of course one plus one equals two. She was very good at math, by the way, much better than me. And then I said, so then why can’t you accept that when the forces of production come into contradiction with the relations of production, we have socialist revolution? I remember her looking not convinced by that brilliant argument. But that was my level of argumentation and my level of fanaticism.

JAY: Even one plus one equals two isn’t right.

FINKELSTEIN: No.

JAY: Even that.

FINKELSTEIN: I wasn’t that level of sophistication in math yet.

JAY: So let’s move on. We talked about your disillusionment with Maoism. Your whole identity has–kind of comes crashing. And so you start to move on. When does Israel-Palestine become such a central issue for you?

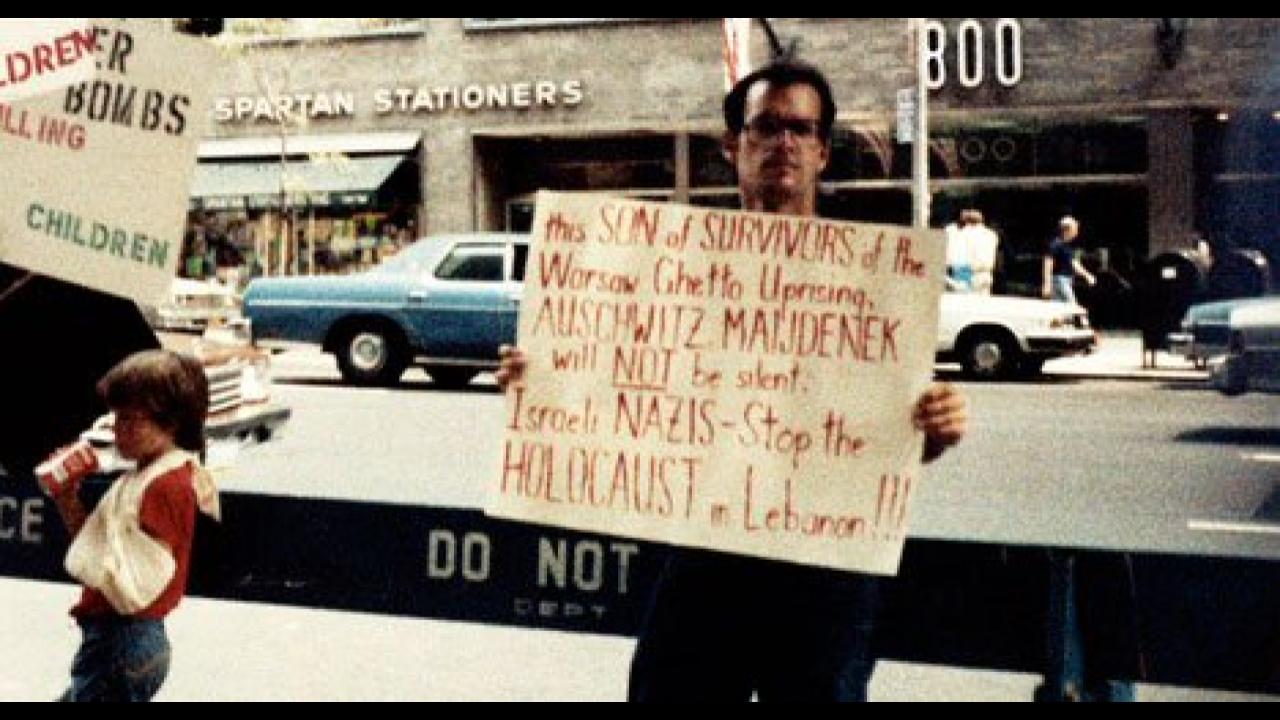

FINKELSTEIN: First of all, it was not on my radar at all. You know, people will say–oh, nowadays people say that I’m obsessed with Israel-Palestine. Actually, I had no interest in it at all. I was involved in the antiwar movement, struggles in Central America, civil rights, things like that. And so Palestine doesn’t come on my radar until the day Israel invades Lebanon in June 1982. I was involved with a small group of meshuga Jews called JAIMIL, Jews Against the Israeli Massacre In Lebanon. I’d like to say that after Sabra and Shatila, that was probably the second biggest disaster of the war, our little group. And we had to have what were called principles of unity. That’s how you form a–.

JAY: Explain that. What does that mean, the second-biggest disaster?

FINKELSTEIN: Oh, Sabra and Shatila was the big massacre.

JAY: No, I know what that was, but–.

FINKELSTEIN: Oh, our group, because we were all crazy (meshuga) Jews, because at that point–you have to remember this is 1982–no normal person was criticizing Israel. It’s true. You had to be little bit crazy. The only one who had sort of, like, intellectual–the two people who had intellectual distinction and were identified with criticism of Israel, the two people were Professor Chomsky and Edward Said. But the rank and file were slightly off–I mean a lot of loose screws upstairs in our little group. Now, of course they would say, including yourself, maybe. That’s for others to judge.

But one of the issues that came up was are you a Zionist or not. And everybody’s anti-Zionist. And I was not going there, because I had my share of–with ideologies. I wasn’t going to go along with it until I knew what I was talking about.

JAY: And the point here is: do you accept there should be a state of Israel or not?

FINKELSTEIN: Well, at that time, to be an anti-Zionist meant that you don’t support the state of Israel. That’s correct. And we had to achieve principles of unity for our group. And it was perfectly obvious that if you deny Israel’s existence, you are confined to a sect or a cult.

JAY: Well, you deliberately missed a word here: right to exist. A lot of people–I mean, Hamas doesn’t deny Israel exists, but some people in Hamas deny its right to exist.

FINKELSTEIN: We can get to that later. At the time, their question was: are you going to recognize Israel? Because if you don’t recognize Israel, then you’ve lost 99.9 percent of the Jewish community. Then what’s the whole point of forming Jews Against the Israeli Massacre In Lebanon? We come to ten, ten Jews. And as you correctly stated, that was interrelated with where you stood on Zionism [incompr.] that’s how it was understood.

And I wasn’t going to go along until I did significant research. I wanted to understand. Now it was no longer just looking for arguments to support my cause; I wanted to be careful what I’m wedding myself to before I did it. And I sat down and I start to read on Zionism, and after about a couple of years I decide, well, what the heck, maybe I’ll turn it into my doctoral dissertation, ’cause I was one of those ABDs.

JAY: How old are you at this time?

FINKELSTEIN: Okay, 1982, so I’m 29. I was one of those ABDs (all but dissertation), ’cause I was going to write my dissertation on the transition to socialism, and then the whole thing collapses. I’m finished with transitions. I’m finished with academia. I worked in the after school program with kids. But then I figure, alright, let’s turn this into my doctoral dissertation. And that’s when I got very much involved in it as an intellectual object.

And so now you had–it was a political–I was politically involved after the June ’82 war. With my dissertation I was intellectually involved. And the fact that I was Jewish of course meant there was now a personal element also to it, obviously, being Jewish and where you stand on Israel. So everything sort of now came together, my political interests, my intellectual interest, and my family interests, because the Holocaust obviously back then was being used even more so than today as a weapon to justify Israel’s denial of Palestinian rights and its criminal policies. So everything now came together.

But still the fact of the matter was, if you ask why I’m still at it today, 32 years later, the answer’s not because I’m obsessed. The answer is because it’s not been resolved. Had it been resolved, I would have moved on. But I could never–in my own mind or heart I could never justify moving on because I’m bored.

JAY: But you didn’t–.

FINKELSTEIN: You know, my closest friend in the occupied territories, Moussa Abu Hashhash, he’s the field representative in the Hebron district for B’TSelem. If I ever told him, I’m bored already with Palestine, I’m moving on, I could never look at him again. What do you mean you’re moving on? I can’t move on (meaning him), so what do you mean you’re moving on?

And it was also, you know, what I got from my parents, that faithfulness: you don’t abandon the cause because you’re bored. That’s not a justification. So I stuck to it. Faithfulness.

JAY: But you didn’t just stick to it. You stuck your neck out. You lost positions in universities. You got–I mean, when you came in here, one of our colleagues here said, you know, you were one of the most hated people. Do you have a bodyguard? I mean, you suffered a lot of slings and arrows.

FINKELSTEIN: I would say I endured slings and arrows. I would never use the word suffering. I know suffering.

The other day I was in Geneva, and I was asked to give a little speech on behalf of a family, four of whom their children are in jail, the Issawi family. Samer Issawi, he was on a 266-day hunger strike. Shireen, who I gave the speech on behalf of, she won the [Alkarama] human rights award. She’s been in jail. When I came back, the son was in jail. And I met the parents. The parents came to pick up the award. Both of them had been in jail. And they put on a very strong face, a very strong face. But then I saw the mother hug one of the Swiss legislators who has been campaigning on behalf of her family, and you saw her just collapse.

Then at the airport I escorted them. We were both traveling through Istanbul. I teach in Turkey, and they were going via Istanbul to Ben Gurion Airport. I escorted them. And we were about to depart. The mother, who, as I said, puts on a very strong face, she just broke into tears. That’s suffering.

Oh, I didn’t mention one of sons was killed. So one son was killed. Currently four children are in jail. That’s suffering.

You know, I’m past 60. I’m in good health. I have a roof over my head. I have food on my table. You can’t call it suffering.

JAY: But were there not moments where you wondered, why do I keep doing this? I’m not sure if everyone knows your story. I mean, it’s pretty easy to go to Wikipedia and get all the detail. But you were ostracized–not just by the Jewish community; by academia, by–I mean, you were not out there on your own, but you were to a large extent out there on your own, and you didn’t flinch.

FINKELSTEIN: No, there was never any moment where I had any thought of flinching. I have my flaws. In fact, I have significant flaws in my character, of which I’m perfectly aware.

But one thing I could say and I don’t think anybody will dispute: I’m not for sale. You know, if–even in what I write, if somebody were to come along, like Sheldon Adelson, and say, oh, I’ll give you $1 million if you change one word in The Holocaust Industry, I could say with absolute certainty I wouldn’t do it. I mean, maybe people don’t believe me. And you can test me, anyone who’s listening. Offer me $1 million to change one word. There’s no way I would do it. Now, when my editor tells me to change a word because I have poor usage, of course I’ll change it. But I’m not for sale.

So there was never any–you know, there are feelings you have. I remember when I came back after I was denied tenure–.

JAY: This is after The Holocaust Industry?

FINKELSTEIN: No, this was after I was denied tenure at DePaul. When I came home, I remember I lie down on the bed, and I was at the time quite close to Professor Chomsky and his wife Carol, his late wife. And I called Chomsky and I said, do you think I did anything wrong? Which is different than do I regret what I did. It’s a question of did I make mistakes for which I should be held accountable. And I remember his answer was, look, Norman, everybody does things wrong, everyone makes mistakes. And that would bother me, self-inflicted wounds which compromise my honor, compromise my dignity. Yes, that would bother me.

But the loss of teaching, I don’t think the price was particularly–I–.

JAY: Why did you write The Holocaust Industry?

FINKELSTEIN: Oh, The Holocaust Industry, actually I have no recollection ever of having written the book. I don’t know why my mind–I don’t remember the process, but I know I wrote it very quickly, because I knew a lot of what was being said was not true. I grew up in my home. My mother used to say (’cause she liked to quote, with purposeful irony, Henry Ford), history is bunk. And you know Ford was an anti-Semite, and she was aware of it. But she liked to call it–there was an irony there, because everything–not everything, but so much of what was being said was just complete nonsense.

JAY: Just quickly, for people who don’t know the basic thesis of the book–.

FINKELSTEIN: The basic thesis of the book is very simple, that I don’t really talk about the Nazi Holocaust itself. There I rely on the best historians and what they’ve had to say on this subject. I talk about its exploitation by mostly American Jews for political and also, at that time, financial gain. There was this whole shakedown racket of Europe called Holocaust compensation, which was completely fraudulent, as I think I convincingly demonstrate in the book. And so it’s about the exploitation. And it wasn’t intended to be a grand, systematic, methodical analysis. The subtitle is Reflections on the Exploitation of Jewish Suffering–just some of my reflections.

JAY: And this had to do with Israel using the Holocaust narrative to justify its–.

FINKELSTEIN: Yeah, Israel exploiting the Nazi holocaust, but also American Jews exploiting the Nazi holocaust.

JAY: Now go back to that group you were in at the Lebanese war and not wanting to get into the debate about should Israel exist [crosstalk] alienating–.

FINKELSTEIN: Oh, no, I wanted to get in the debate, but I wanted to get in the debate with knowledge. I’m not going to do it because it’s an ideological fad. I sat down and I started to read on the subject.

JAY: Okay. But my point is is that that book, a lot of people thought, a lot of Jews who didn’t degree with you–I mean, a lot of Jews did agree with you and agreed with the book.

FINKELSTEIN: Well, not a lot agreed with the book, not that [incompr.]

JAY: But, well, that’s kind of my point, that it was considered inflammatory, that you didn’t have–even though–I think even people that agreed with you thought you didn’t have to kind of get, say that the Holocaust was being misused, ’cause it was just too sensitive a topic.

FINKELSTEIN: Well,–.

JAY: [incompr.] second thoughts of having written it?

FINKELSTEIN: Oh, no, not at all, because, as my publisher said, the reason that book, unlike all my other books, that book actually succeeded and reached a wide audience, he said I was just a little bit ahead of the curve. It was already people were sick and tired of the Nazi holocaust. You remember the famous line or infamous line by Jesse Jackson. It was, like, 1987 [or something he said, oh, I’m (?)] sick and tired of the Holocaust, and he got really attacked for it. But people were getting–it was obvious it was being used or put to crass purposes. So I was just a little bit ahead of the curve.

Nowadays the book is not even controversial anymore. So everybody refers to a Holocaust industry. Even Avraham Burg, the former speaker of the Israeli Knesset, he wrote a book on the Holocaust about four years ago, and about page six or page eight he refers to, quote, the “Shoah industry”, Shoah being the Hebrew word for Holocaust. The Shoah industry is just a commonplace nowadays. So there’s nothing particularly controversial anymore in the book. So I don’t have any regrets about it.

And for me it was a sort of–my parents at the end, they didn’t care how the Holocaust was being used and exploited. History is bunk. Who cares? I cared. It did bother me that my parents’ suffering was being used for really nefarious purposes to justify the criminal policies against the Palestinians. That did bother me.

JAY: Okay. We’re going to move kind of a big jump ahead now, because Norm has got a train to catch, and he’s going to come back again sometime and we can kind of pick it up.

“Norman Gary Finkelstein is an American political scientist, activist, former professor, and author. His primary fields of research are the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the politics of the Holocaust. He is a graduate of Binghamton University and received his Ph.D. in political science at Princeton University.”