The Necessity for Higher Wages – Heiner Flassbeck on RAI Pt 4/5

Mr. Flassbeck, former head of UNCTAD, says we’re going into the Japanese scenario, a stagnation with a kind of deflation because we have no purchasing power in the hands of the mass of the consumers. This is an episode of Reality Asserts Itself, produced July 31, 2014, with Paul Jay.

STORY TRANSCRIPT

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome back to The Real News Network and Reality Asserts Itself. We ‘are continuing our series of interviews with Heiner Flassbeck about the state of the global economy and what we can do about the crisis. And Heiner joins us again in the studio.

Thank you.

DR. HEINER FLASSBECK, FMR. DIRECTOR, UNCTAD DIVISION ON GLOBALIZATION AND DEVELOPMENT STRATEGIES: Thank you.

JAY: So, one more time, Heiner worked at UNCTAD (, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). From 2003 to 2012. He was the director of the Division on Globalization and Development Strategies. He now is director of Flashback-Economics, a consultancy for global macroeconomic questions. And you can find him at Flashback-Economics.de.

Thanks for joining us again.

HEINER: Thanks for having me.

JAY: So, several times over the course of this series you’ve talked about the need for higher wages. We’re in the Real News Center in Baltimore, and the other day I had an interesting conversation with one of the plumbers. And we were talking about whether minimum wages should go up in the United States. And I was saying this thing about $10.10 an hour that President Obama’s calling for, it’s kind of disingenuous, because $10.10 an hour is better than $7 or $8 for sure, but it’s not really going to get people out of poverty, which is what he claims. , and the living wage demand for $15 is at the very least where things should be. And he says to me, well, what is the point? If you get this racemize in minimum wage, it may cause other wages to go up as well, and then they’re just going to raise the prices. So what’s the point? Because everybody will be right back where we were again, were before.

HEINER: That’s right, insofar if we would have unreasonable wage increases, say, of 10 percent, as we have had in the past sometimes, during the oil price explosion. So then it would go into crisis. That’s for sure.

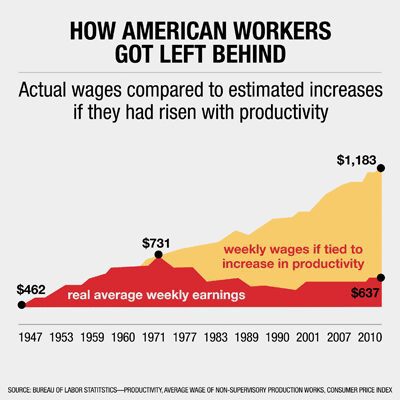

But what we have to reinstall, so to say, is the normal part of the wage increase, namely, wages following productivity. Real wages can follow productivity without any problem for the overall economy, without igniting inflation, nothing like that, but with very stable inflation rates. And this we have lost in the last years.

JAY: Well, back up for a sec. We talked about that earlier, but even if wages go up according to productivity, the plumber’s going to say, well, why can’t they raise prices anyway?

HEINER: No, they wouldn’t, because then we have to hope at least that there is certain competition in the market that avoids people from increasing prices beyond that. And this is true. This we can show. I mentioned already we have the very strong relationship between unit labor costs all over the world for the United States for very long periods of time, between unit labor costs and the prices and the inflation rate. So this is very stable. And sometimes you have movements where capital is winning more, which is the last 20 years, but labor lagging behind. But overall, if we have an increase of wages, there would be no inflationary bouts. That’s absolutely clear. And this is at least the one mechanism, the competition in the market that prevents the system then from doing artificial, –so to say, artificially increasing prices. That doesn’t come out.

JAY: There’s enough competition to stop it.

HEINER: Yeah, it’s still enough [crosstalk]

JAY: Even in the sectors that are highly monopolized?

HEINER: Well, that’s not quite clear, whether it’s everywhere. But for the overall economy, this is very stable. So we can still trust on that, that it will be the outcome. But what we have to reinstall, as I said, we have to reinstall the rule that wages should follow productivity plus the inflation target, which means that real wages should rise like productivity. This we have lost in the last 20 or 30 years.

JAY: At least the last 20 or 30 years, but if not even more, the low end of the wage scale is far below.

HEINER: Yeah. Then comes, in addition, the effect that is very strong in the United States, much stronger in the United States than in Europe, for example, that we have the inter-wage structural changes that –the major part of the wage increase is going to the upper end, where the bankers and all these people are [crosstalk]

JAY: It previously had been more balanced than that because of more unionization.

HEINER: Yeah, where we had a balanced increase because of unionization. This is for me very clearly a point where the government has to step in. What we need is to reinstall the rule that everybody should get the productivity increase, because the productivity increase is not produced by the bankers. The bankers are just taking it.

JAY: If your formula had been followed, what do you think would be the minimum wage now?

HEINER: Well, if the minimum wage would have been dynamized in that way and if we put it on the productivity, then it would be, I don’t know, beyond $15. It would be beyond–.

JAY: I think I’ve seen–yeah, I’ve seen numbers like $20 an hour.

HEINER: Yeah, it would be beyond, clearly beyond. If you look at the–I always take the example of the nonsupervisory workers in the United States and –in the statistics called the nonsupervisory workers nonsupervisory workers. If you look at their wage from 2000 to 2013, there is no increase in real terms. If you look at that, there is no increase for the whole bunch of these people, nonsupervisory workers. So normal workers have no real increase at all. And this is a scandal, because they have produced the productivity, they have, so to say, generated it. And they are excluded from that.

JAY: So if now government were to say the minimum wage should be now what it would’ve been if this had kept up in the formula you’re giving, say, around $20 an hour, would that now be inflationary, if it was raised to $20 an hour?

HEINER: No, not for the minimum wage as such, no, no. The minimum wage is not so important as–it is not overall wages. It’s just for–.

JAY: But that would have effect on wages generally.

HEINER: It would have an effect of wages generally. But what I’m asking for is not, so to say, to turn around the whole process by now having explosive wage increases. But when at I say: reinstall that rule,. This still leaves the people the wage share, so to say, at a rather low level for the moment, because it’s impossible to change it. By pushing for very high wages–, we really produce inflation. So the system is such that what you can do is you can reinstall the rule that people get equally share in the productivity increase, which is politically a thing that has to to be pushed through. But this would even imply that the wage share remains at the low level where it is now.

JAY: Well, what do you make of this $10.10 demand? ‘Cause it seems almost–I mean, it’s not symbolic if you’re making $8 to go to $10.10. But a family with one kid at $10.10 is still in poverty.

HEINER: Yeah, it’s ridiculous. Like, in Germany–

JAY: It seems more like an election ploy.

HEINER: –in Germany we’re talking about 8.50 euros, which is something very similar to $10.10, but it’s clearly not enough. And Switzerland, the country where I’m living very close to, Switzerland, so there they’re discussing now–they have an initiative that would go to the electorate for 22 Swiss francs, which is $18 or something like that, no? This is something–no, it’s more. The dollar is the other way around. It’s 18 euros, but it’s $25. They’re talking about $25 as the minimum wage in Switzerland. And Switzerland has more or less the same productivity as the other countries have.

JAY: Well, let’s look at what’s going to happen in the United States. In all likelihood, even $10.10’s not going to get passed. It won’t get through the house.

HEINER: No. Yeah.

JAY: And the Democrats could easily be losing the Senate in the next election, which kind of boggles the mind. And $10.10 ain’t enough anyway. So where are we headed, then? If your analysis is that the only possible recovery is a wage-led recovery and we’re still going the other direction, so then what?

HEINER: Yeah, we’re going into the Japanese scenario that I mentioned already, stagnation with kind of deflation, because we have permanent pressure on wages, we have no purchasing power in the hands of the mass of the consumers. And this is the perfect scenario. Monetary policy could, so to say, by producing this perceived wealth in the hands of a few, could paper over this process for a short time. But it will not go on forever. No, we have to come back, and it will happen in one way or the other, maybe after the next crisis, that we have to understand and we have to come back to a point where we have to say, everybody has to get the productivity increase. Otherwise the economy cannot work.

But people are shying away from that. Larry Summers, my former colleague Larry Summers, just had a piece in The Financial Times talking about growth policies and I don’t know what. But it wasn’t clear what he’s talking about. He doesn’t even say what he’s talking about, what the growth policies are. He says we are in a kind of secular stagnation, but he doesn’t say what is the policies, because he’s shying away from saying, well, you have to intervene in the labor market and go for higher wages.

JAY: But they don’t want to open that door.

HEINER: No, nobody wants to open that door.

JAY: When the G20 was in Toronto, we did a piece on The Real News where we looked at the final declaration of the G20 countries, and we looked through the whole document to see if we could find one use of the word wages, and he couldn’t find one. We found one sentence which talked about the need to increase demand, which implied higher wages. And where was that? This should happen in China, not here.

HEINER: Not here. No. But even people who are asking for more expansionary fiscal policies, like Larry Summers or Paul Krugman, they’re not talking about intervention in the labor market. But this is what is absolutely needed, because there is the imbalance. It has nothing to do with the market economy. If the one side is extremely strong and can dominate the other side,. If capital can dominate labor, you don’t have a market result. But the economists are living with the fiction that this is a market result. You have extremely strong companies for a thousand reasons–because they are rich, because there is high unemployment, and so on, but still there should be an outcome like in a market. It’s absolutely ridiculous.

JAY: Yeah, it’s okay for the state to intervene in labor law that it makes it very, very difficult to organize unions in the United States. And that kind of state intervention, that’s quite alright.

HEINER: You can do it wherever you want. You can do it on the price side directly. You can give a guideline for wages.

JAY: No, I’m saying, for their argument, they don’t mind if the government steps in, rewrites labor laws, makes it difficult to have unions. That’s okay. Or recently–where was it?–in the southern United States, I think in Georgia, where politicians intervened to prevent unionization.

HEINER: The little unionization that is still there, to get rid of it, abolish that, that is okay, yeah, because this is the dogma. The dogma is you don’t intervene into that market. You’re happy with the power of the capitalists, but you don’t [crosstalk]

JAY: Okay. Okay. So we’re still in search of our rational, reasonable capitalist. We’re going to see in the next segment of we can find our rational, reasonable capitalist. And so please join us on our Don Quixote quest in the final segment of our series of interviews with Heiner Flassbeck on The Real News Network.

END

Podcast: Play in new window | Download