The Promise and Limitations of Worker Co-ops – Gar Alperovitz on Reality Asserts Itself (pt 4/5)

This interview was originally released on January 27, 2014. Mr. Alperovitz tells Paul Jay that the experience of Spain’s Mondragon, the world’s largest workers’ co-op, shows that workers’ ownership can go to scale, but on their own co-ops will not transform society or the economy.

PAUL JAY, SENIOR EDITOR, TRNN: Welcome to back to The Real News Network. I’m Paul Jay in Baltimore.

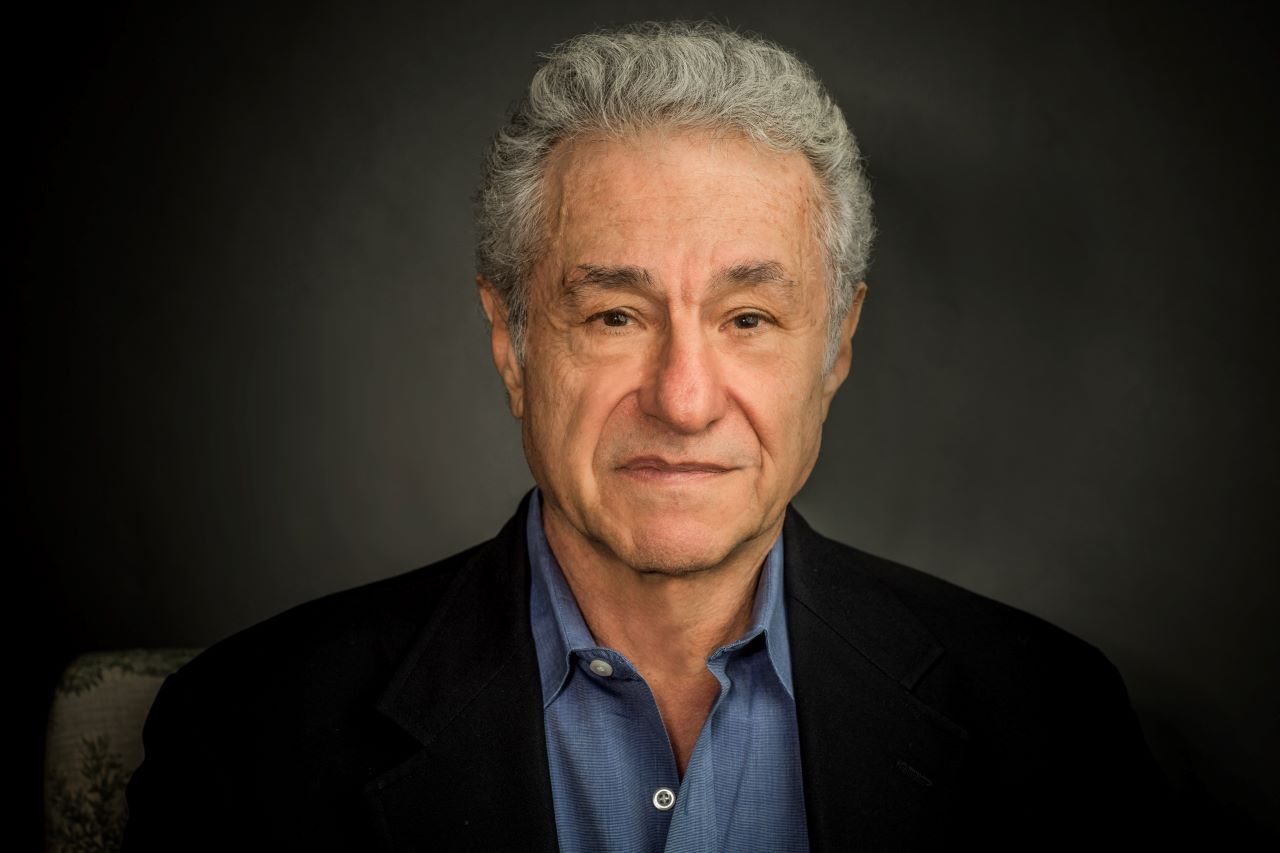

This is Reality Asserts Itself. We’re continuing our series of interviews with Gar Alperovitz. And Gar now joins us in the studio again.

Gar is the Lionel R. Bauman Professor of Political Economy at the University of Maryland, cofounder of the Democracy Collaborative. His most recent book is What Then Must We Do? Straight Talk about the Next American Revolution.

Thanks for joining us again.

GAR ALPEROVITZ, COFOUNDER, DEMOCRACY COLLABORATIVE: Thanks.

JAY: So, Gar, you’ve talked a lot about the importance of workers co-ops. And probably the most outstanding, largest gone-to-scale version of workers co-op is Mondragon in Spain, which is a multibillion-dollar business with different divisions and all kinds of production. And for a lot of people, people were saying, well, this is kind of the future and this is the way to transform the society.

Well, in spite of all its success, Mondragon did not transform Spanish society, economy, or politics. And then, more recently, the Fagor division, which does electronics, washing machines, and dishwashers and such, essentially has gone bankrupt because they couldn’t compete with cheaper Chinese products in the collapsing Spanish economy and such. So talk about, you know, what we can learn from Mondragon as a positive, but also the limits of building workers co-ops in terms of bigger transformation.

ALPEROVITZ: Yup. It’s a very important point. I just did an article on this, this subject, ’cause it raises a very important strategic issue for thinking about how we want to organize our own economy.

Mondragon is, you know, 80,000 workers involved in maybe 85 co-ops–or it depends how you count it, count them. And it’s been very successful, very participatory. This is the plus side. Wages, top to bottom, the ratio in 80 percent of them were six-to-one. American corporations it’s 250- to 300-to-1, top to bottom. So very democratic participation. In a few of the larger ones it was slightly worse–nine-to-one, eight-to-one. So it’s a very democratic distribution of income compared with the corporate system, and more democratic participation. So there’s a lot to learn.

On the other hand, they are operating in the global market, they’re operating in the Spanish market, and they are totally dependent on the conditions of capitalism in those markets. And as we’ve just seen, one of the big, big units collapsed. And the other units, usually they try to support each other. The other units couldn’t.

JAY: Well, even in the collapse, Mondragon’s done something no big capitalist firm would do, which is they’re using their own insurance company to guarantee wages for the laid-off workers for two years, and they’re going to try to find other jobs for them.

ALPEROVITZ: Absolutely.

JAY: So even at that level it’s better than what the alternatives would have been.

ALPEROVITZ: Absolutely. And no one should be–it’s a very important, a very positive experiment. And it’s within limits, because it’s dependent upon the world market and also the vicissitudes of capitalism. And so it’s got difficulties.

So when you actually ask what ought to be done with co-ops or things like Mondragon, they could be part of the new economy. I think that’s certain.

But if you get to a significant scale–and Mondragon and Fagor, that division, were large-scale–you’re really up against–either the economy has a certain planning capacity or you’re up against the markets and you’re faced with what’s happened to them. So, for instance,

next time General Motors collapses–and I think there will be a next time–and Chrysler–we just took them over. The government bailed out that big company, made it–socialized it. It became a nationally owned government company. U.S. taxpayers owned it.

What we ought to be doing, thinking about this model, is building mass transit, high-speed rail, turning that into a transportation company with taxpayer money that’s going to pay for it anyway–that’s what we’re doing now–and then begin using our planning for transportation as a society, the government to begin saying, okay, this is how many roads, this is how many rails we really ought to have, moving away from all the highway system, moving away from flights as well. The rails is much more efficient than flights if you [incompr.] and supporting cities by having adequate transportation. We’re now–the airlines are cutting out of cities like Cincinnati. The whole city’s going to go down. We ought to have a transportation plan that will tell you how many rails and how many buses and how many trains you need. And then you produce to the plan and you have stability because you have a plan.

Now, I don’t think the entire economy ought to be planned, but major segments of it can be planned and solve the problem of companies facing unemployment like Fagor.

JAY: Well, major sectors of the economy are already planned.

ALPEROVITZ: Yes.

JAY: It’s just they’re owned privately. Like, probably maybe the most brilliant piece of planning and the largest private employer in the country is Walmart.

ALPEROVITZ: Yeah.

JAY: Walmart is an incredibly planned economy. It’s just owned privately. And there’s no–you know, it’s planned in a way that workers are paid terrible wages. But if you had, for example, a publicly owned Walmart that paid decent wages, it would have an enormous ripple effect throughout the whole economy.

ALPEROVITZ: That’s right. And that planning takes place in every major corporation.

JAY: I mean, they–you take a tube of toothpaste off a Walmart shelf, they know–and somewhere in Asia another tube of toothpaste has to be produced. You can’t get more planned than that.

ALPEROVITZ: Right. I hope we can move that back and have the United States begin to do that rather than Asia. Yeah, that’s a whole ‘nother set of questions.

But planning takes place. We know how to do that.

Now, there is a whole question about democratic planning, which means that the society has to produce a democratic capacity. Right now the corporations control a lot of the politics of this. So when you say planning is necessary–and it is necessary to deal with Mondragon, Fagor, these problems we’re talking about, to deal with transportation–then you’re also saying we need a democratic society, because otherwise the corporations will control the national planning. So you’re talking about really changing the whole nature of the substructure of the system.

JAY: Well, you’re talking about who has power.

ALPEROVITZ: Who has power, because the planning system’s going to be controlled by somebody, and it’s either the corporations or we have to–and to say that is to say, you want to play this game about changing the system? The chips are three decades of your life. We’re talking about big-time build from the bottom, begin to reshape from the neighborhood, from the worker-owned co-ops, from the cities, some of the really interesting things that you’re doing here in Baltimore, beginning to build up knowledge, ideas, experiments, a program that actually is practical and look at it as a 30-year strike, as a strategy at least to begin to deal with the power of this system. So that’s the name of the game.

JAY: And, I mean, it flows from the idea that concentration of ownership gives rise to concentration of political power.

ALPEROVITZ: Yes.

JAY: So you need to change the way things are owned.

ALPEROVITZ: That’s the central element. Systems–you know, in feudalism it was land; who owned the land had the power. Capitalism, who owns the capital has the power. State socialism, there was a form where the state controlled it, and it could have been democratized.

JAY: Well, it was another form of too much concentration of ownership, because the party winds up controlling the state, so the party now has the concentration of ownership, and you wind up with the same kind of–similar kind of problem. I can’t say the same kind, but it’s a similar kind of problem.

ALPEROVITZ: Yeah, exactly, which tells you that the model that we want to build has to have democratized ownership, but democratized in a way that builds from the bottom up, so that the concentrations of power are not overly concentrated, that the terms are whether–appropriate to the scale. So little co-ops in some places, city-owned in other places, neighborhood-owned in other places.

JAY: State-owned.

ALPEROVITZ: State-owned. Regional. The Tennessee Valley Authority was designed, in the initial stage, as a way to do ecology of the river and power. It got taken over.

JAY: But there will still be some things at a national scale–

ALPEROVITZ: And then there’s national.

JAY: –which are going to have to be nationally owned.

ALPEROVITZ: Absolutely. And then there’s national.

But, again, the principle–I call it a pluralist commonwealth, pluralist commonwealth. The principle is you always stay at the lowest level necessary and only go up if you have to, so that you keep it closer to democratic processes. So that’s the kind of vision that at least we’ve been trying to develop and begin to get–you know, and get very real about it in terms of what’s on the ground. There are places around the country where almost everything we’re talking about is already being done in one form or another. It’s practical. And if it isn’t practical–.

JAY: What are some of the best examples?

ALPEROVITZ: The best examples of–for instance, in Cleveland there is an extremely interesting–and many other places are doing something like this–there is an extremely interesting–neighborhood is 40,000 people, mostly black, unemployment 40 percent, average family income $18,000. Really beaten-up neighborhood. Well, there’s a complex–.

JAY: Average family income $18,000?

ALPEROVITZ: Eighteen thousand. That’s right. In that neighborhood, there’s a community-wide structure, nonprofit corporation, and worker-owned cooperatives which are subordinate to it but work together, so they kick in a little bit of profit in order to start new ones. And they–not just little ones. There is the largest urban–the largest urban greenhouse in the United States is one of these things. Three million heads of lettuce year–that’s the scale we’re talking about, not that–people think co-ops, they think little tiny things. There is a huge industrial-scale laundry. There’s another, a different co-op that–it’s very green. It uses about a third of the water and a third of the heat. And then there’s others being built each year. But the point is that some of the money goes to build the neighborhood, some of it goes to start new co-ops.

And then they use the purchasing power of universities and hospitals in that area. So Case Western Reserve University, the Cleveland Clinic, university hospitals, they’re right in this poor neighborhood. They buy three billion–with a B–dollars in goods and services, plus the salaries, plus their construction, just what they buy–none of it from this neighborhood beforehand. But now they’re beginning to shift some of it–a lot of public money there, too–Medicare, Medicaid, education money, taxpayer money–they’re beginning to shift to this purchasing to help rebuild the neighborhood. That’s a really interesting model, ’cause it has very decentralized ownership, but you’re using essentially quasipublic resources to help do it.

And many other cities are waking up to the fact they’ve get the same situation and they can do it. So Atlanta’s now beginning to do it, two or three are going to be in the Washington, D.C., area, several around the country, beginning to see–you can begin putting down these principles, these practices practically.

Interesting other thing about this which is very important, particularly for liberals and the left to think about: if you’re doing this kind of work and it’s practical and it really is serious, not rhetoric and slogans, you find people who think of themselves as moderates and conservatives, small business people, who say, that’s a good thing to do at the local level. These are not the national ideologues. And you find–that’s an intelligent–people working hard, they’re trying to better the neighborhood, trying to better themselves, they’re doing productive work. That’s a good idea. And we’re surprised at how you break through ideologies if it’s practical.

JAY: Now, the critique of Cleveland model and co-ops is somewhat a little bit what we talked about, the limits of Mondragon, which is it’s good for the people that are working there, but it’s not transformative to the city, to the state, and it doesn’t change who has power. Like, you still have, you know, a tiny handful of people and/or corporations that control the commanding heights of the economy and thus have–control the commanding heights of the politics, and the basic structures don’t change. So even if these are kind of, you know, nice shape of things to come, to be transformative, something at the political level has to happen [incompr.] change who has power.

ALPEROVITZ: I totally agree with you. These are–at this stage, I think–I’m a historian and a political economist. You don’t talk about any of this without throwing some decades on the table. At this stage, we’re developing the new models. And we are. That’s because of the context. The reason this is happening is because of the economic pain coming out of stalemate and stagnation. And you can’t get the old liberal programs passed. There’s no money. So people either–.

JAY: Well, there is the money. They just won’t tax it.

ALPEROVITZ: Well, they won’t tax it, yes, in theory, but you can’t get it. The labor unions are not powerful enough to support liberal–. The whole thing is: what used to be possible is no longer possible. So the pain levels are growing, and it’s either go in this new direction or it gets worse.

You’re absolutely right, though. The next stage is whether or not a political component begins to pick up on that and begin talking seriously about city government.

JAY: And there are some signs of that, too. I mean, there are some places where you have these kind of–you know, I don’t know too much about it, but I’ve heard in Richmond, California, you have a green mayor, and they’re using eminent domain to stop foreclosures. There’s–a sort of progressive agenda’s been elected in Jackson, Mississippi.

ALPEROVITZ: Yes.

JAY: I don’t know how it’s going, but the program they got elected on looked pretty good.

ALPEROVITZ: No, but it’s very interesting, and, again, you know, as a historian. You’re beginning to see this pop up. Oh, the light bulb’s going on. Here’s all this experimentation in economics. And that is happening, even though the press doesn’t cover it. It’s really out there.

Website, by the way: Community-Wealth.org. Really check it out, ’cause it just covers this stuff.

But at some places you’re seeing, oh, the next step–we’re going to have to start talking about city government. And that is beginning to be experimented. We’ll have some failures, we’ll have some successes, and we’ll learn the next step in other places.

I think it’s really–I think this is–you know, I’d be cautious about this, but I think this may be the most important time in American history, bar none–and I would include the Revolution–because I think we’re running to the end of the possibilities available in the current structure and people are being forced to innovate and think through vision and get serious about this stuff rather than rhetorical.

JAY: Well, if necessity is the mother of invention, we should be living in interesting times.

ALPEROVITZ: Exactly.

JAY: Okay. In the next segment of our interview, we’re going to ask Gar a question which we plan to take up over the next few years: what would Gar do if he ran Baltimore, if he ran Maryland and had a progressive or agreeable city council, even an agreeable state legislature?

What would you do? I’m going to ask you that.

ALPEROVITZ: Okay.

JAY: So please join us for the next segment of our interview on Reality Asserts Itself with Gar Alperovitz on The Real News.

“Gar Alperovitz is an American historian and political economist. Alperovitz served as a fellow of King’s College, Cambridge; a founding fellow of the Harvard Institute of Politics; a founding Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies; a guest scholar at the Brookings Institution; and the Lionel R. Bauman Professor of Political Economy at the University of Maryland Department of Government and Politics from 1999 to 2015. He also served as a legislative director in the US House of Representatives and the US Senate and as a special assistant in the US Department of State.”