Workers’ Movements in Revolutionary Iran and Europe – Saeed Rahnema part 2/2

In part 2, political scientist Dr. Saeed Rahnema discusses his experience in the workers’ council movement leading up to and during the Iranian Revolution of 1979-1980 and addresses the Islamic Republic’s opposition to unions. He also contends that modern-day working classes in the West are ideologically and culturally segmented and that the left has failed to mobilize at numerous historical junctures.

The (In)conceivability of Real Workers’ Control – Saeed Rahnema part 1/2

Talia Baroncelli

You’re watching theAnalysis.news, and I’m your host, Talia Baroncelli. This is part two of my discussion with Dr. Saeed Rahnema. Feel free to watch part one first if you haven’t done so already, and also help us out if you can by going to our website, theAnalysis.news. You can hit the donate button at the top right corner of the screen and, most importantly, get onto our mailing list; that way, you never miss new content. See you in a bit with Dr. Saeed Rahnema.

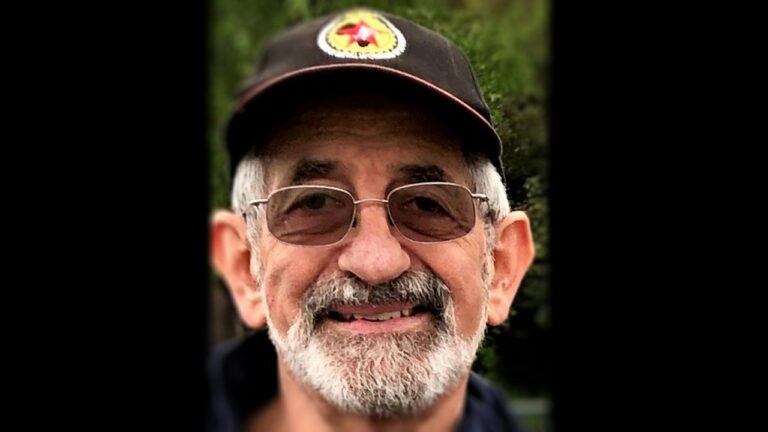

I’m very happy to be joined by Doctor Saeed Rahnema. He is a retired political science professor as well as a professor of Public Policy at York University in Toronto, Canada. He was the director of the York School of Public Policy and Administration and the director of the non-profit Middle East Economic Association. He was born and raised in Iran and was a member of the Industrial Management Institute there during the Iranian Revolution of 1979. He was a leading activist in the Left and Workers Council movement, as well as being a founder and member of the Executive of the Union of the Workers and Employee Councils of one of the largest industrial conglomerates in Iran, known as IDRO.

His recent publications include The Transition From Capitalism as well as Neoliberal Imperialism: The Latest Stage of Capitalism. We’ll be discussing some of these works in future interviews, but today we’ll be largely focusing on workers’ councils. It’s really great to have you here, Dr. Rahnema. Thank you.

Saeed Rahnema

Thanks for having me. Good to see you.

Talia Baroncelli

There’s one other thing that we should address before we get to the issue of democracy, and that was something that you also mentioned in the article. Gramsci said that the problem will lie within the proletariat itself. You already addressed this, that there is this required socialization, and sometimes the working class might not have, or you question whether they have the ability to actually raise certain demands or certain radical demands that are necessary to enable or initiate a transition away from capitalism and towards taking political power and towards having workers’ control. So you’re speaking about this hegemonic aspect of the mentality of the working class, the adoption of certain bourgeois values.

Would you say that’s still relevant in light of what you just spoke about, how the working class has changed over time? How do you evaluate what Gramsci, Antonio Gramsci, was talking about back then following the April strike, and how would you apply it now?

Saeed Rahnema

Well, definitely. If workers are the main protagonists and agents of such a major transformation, obviously, they should be prepared for it ideologically, socially, politically, culturally, and organizationally. Unfortunately, we don’t have this situation.

First of all, of course, we have not limited this discussion to any particular part of the world. We have many areas of the world that do not have unions. In my original country, Iran, after over 150 years of a struggle for democracy and several major revolutions, the workers do not have a union. They’ve got Islamic associations, which is a different situation. Even in those cases that we have unions, we have great unions in Europe, and in North America. At the same time, those unions are also very bureaucratized. They need to be reformed. They need to be radicalized. The reason why the working class is weak is partly because of the failure of the left. The left in the West, it’s a very different story. They have not been able to take advantage of all the problems that the working class and other people face in a capitalist society, particularly in the present post-Keynesian neoliberal aspect.

I think that’s why it’s very significant that there should be changes so that the working class would be prepared and ready, and why participation is important, because participation is also a learning process. When workers sit in management, they also learn how to be managers of their own companies’ legislation. There are so many other things. The working class, apart from its segmentation ideologically, is also very differentiated. We should not forget that.

This is so tragic to see in many of the advanced capitalist societies; a significant number of the working class votes for the right and far-right parties. In the United States, Trump gets a lot of support from the working class. All of this shows that there are serious problems and there should be lots of effort in order to be able to organize because it’s not enough to say that workers should go and control the production. How should they do it? We cannot do it without a change in the political system. This is, if I want to reduce all of my discussion, you cannot have workers control at the production level without having a progressive, radical state in power.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, what is required for this radical progressive state or what are the components of it? Again, you mentioned democracy before.

Saeed Rahnema

For me, this is a totally different topic. I have this book.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, we don’t have to discuss necessarily the exact transition, but I just mean, what is your conception of democracy? In this word itself, there are different meanings of democracy. Some scholars would say, “Oh, to have democracy, you actually need a market. You need market capitalism in order for it to work.” Others would say, “That’s not a reflection of reality.” Others would say, “There’s popular democracy, there’s liberal democracy.” Some would say, “These are just different terms to ignore the fact that there still are large inequalities within democratic systems, and they’re not really democratic.” My main question is, what really do you mean by the word democracy?

Saeed Rahnema

There are two answers. First of all, I would say that the movement onward should be democratic. This is one. I’ll explain what type of democracy I have in mind. Why should it be democratic? Present society is not the two-class society that was expected— a minority bourgeois and a majority the working class. In today’s societies, we have the new middle class, we have the traditional middle class or the traditional petite bourgeoisie, and we have the, I don’t know a term for this: underclass, or any term that you use for totally marginalized people. We have got, in a sense, five classes, not two classes.

At the same time, today, we have the so-called identitarian groups. We have feminists, we have environmentalists, we have peace activists, youth, and others fighting for right causes. The argument is that the working class is not the sole agent of change anymore. I think it was never, but now it’s very obvious. That’s why, in order to have it, we cannot have the idea of just workers and the dictatorship of the proletariat and others. We need to have a combination of all these classes and identarian groups to gradually weaken capital and the capitalist class and then move step-by-step forward. This is the democratic nature as opposed to a dictatorial revolutionary type that I was a believer in during the revolution, but now I reject it.

As for what type of democracy, well, of course, democracy has different meanings, and liberal democracy has its own problems. We know the problems with, for example, the democratic system in the U.S., in Canada, in Germany, and everywhere. The idea is that we should move toward the type of parliamentary democracy in which you have representation of a vast number of people in order to establish a progressive government and that progressive government comes up with progressive policies. Part of it is free education for all, a reduction of class differences, and others. It’s not the end. This democracy is a means to be able to reach the final goal of transition from capitalism, which has a completely different system, but still, it is democratic. Even in the post-capitalist society within the state, I also have different views from the critics of the [inaudible 00:11:46] program. I think the so-called first phase of socialism, we need to have a state and we need to have representation.

Talia Baroncelli

Lastly, how would you say your experience in Iran, being involved in councils there and also living there throughout the revolution of 1979, going into 1980, how has that experience informed your view? We started off with this question at the very beginning, but perhaps you can add a bit more of your own personal experience to this discussion.

Saeed Rahnema

Before answering that, I forgot to discuss a bit about my notion of radical industrial democracy if we have time.

Talia Baroncelli

Of course. Go ahead.

Saeed Rahnema

Talking about democracy, democracy has two levels: the political level, which is the political democracy, and the production and also social institutions where we have industrial democracy. Industrial democracy, I discuss it in a way that there is a tri dimensional matrix. We have degrees of participation. The lowest would be information sharing, then consultation, then co-management, and then finally self-management, which is workers’ control. We have the organizational levels from the shop floor to the level of the factory, the level of the company, depending on how large, and then in different areas from human resources to production and sales and management.

My argument is that the stronger the working class and trade unions, the higher would be the degree of participation. If workers are weak, we cannot have information sharing, as in many cases in many different parts of the world. If we are stronger and gradually move toward higher levels, such as co-management, co-management is the radical participation of workers in this process. I think this is very significant that we deal with this.

How is this operational? I argue that, first of all, we need to have a democratized union. I do believe in unions. We need to have unions. I don’t agree with councils that say we don’t need unions. These unions should be democratized, and each of them should have a participative arm, which could be a participative council. This council is different from the managerial council. Since most of the large factories now operate downstream, they have huge upstream and downstream companies, then we have different stakeholders. We have representatives of each of the councils from the whole cluster create the stakeholder councils and they participate in the work. The stronger they are, the more important role they can play. This is very brief; of course, this is my notion of industrial democracy.

Talia Baroncelli

You’re speaking about the importance of unions, which didn’t exist when you were in Iran. How would you say that affected the situation there, not having unions?

Saeed Rahnema

Very much. If we have time, just very briefly, I mentioned that the case of Iran is hugely significant. Unfortunately, in almost none of the workers by non-Iranian theorists on councils, there has been no mention of it. Ironically, to my knowledge, this was the widest and the most expansive range of council movements than any other revolution.

Imagine all the industries of Iran, all ministries of Iran, all government agencies, private sector, they had their council, some of them before the revolution. These were strike committees that turned into councils. Many of them after the revolution, even in terms of socialization, the government also had to socialize to nationalize almost all the major industries; 990 industries were nationalized. They were among the nationalized. We had all of these things. In no other revolution, you have this. Unfortunately, because of internal problems, because of theoretical confusions most of us were equating this with the Soviets, which was a wrong notion. We should have compared them to the workers’ committees and the factory committees in Russia. There were internal divisions, and then there were no unions and no experience of unions to support it because neither did we have real unions under the Shah nor later. This was severely weakened.

Then, of course, the most significant aspect that led to its demise was the state. Although the first national government, the Islamist nationalist liberals, when they came into power, they tolerated councils because they were not powerful enough themselves. They did not like the councils. They did not support the councils. Most of the factories needed heavy subsidies. They were based on heavy subsidies that they could not operate without the help of the government. The government was not ready to do so. After the hostage crisis at the American Embassy, the hardcore Islamists came into power, and they expelled us all. Some were jailed, and some were executed. That was the end of the councils. It was very tragic.

Talia Baroncelli

Well, perhaps this nationalization that you talk about, which was such a large part of the Iranian revolution and wasn’t really a large part of previous revolutions in the West, was due to what a lot of the revolution stood for. That was to regain control of the country’s resources. Mohammad Mosaddegh was democratically elected and was then overthrown by a coup that was led by British Intelligence as well as U.S. Intelligence, the CIA, etc. Mosaddegh was largely arguing for reclaiming the country’s resources from the Anglo oil company.

I think maybe the nationalization that took place during the Iranian revolution of 1979 was probably a response to the modernization of the Shah and the Shah’s outlook towards the West and wanting to be friendly with the West. You could say that maybe it was reactionary, but I’m sure some of that was the stance against the West to ensure that they were reclaiming and protecting their own resources, hence nationalizing them.

Saeed Rahnema

Yeah, no doubt. There is this background that you have during the Mosaddegh era, which unfortunately was toppled by the CIA and MI6. In addition, one of the reasons that most of these industries had to be nationalized is that, during the revolution, some of the private sector owners either fled or were deposed by their councils. In the government-owned industries, many of the managers were expelled by the councils. There was no other choice for the government to nationalize. Of course, disastrously after that, when the Iran/Iraq war started and ended, the Islamists, the same regime in power, they so-called privatized those, giving them either free or below market to their own cronies. That’s why now we have very few nationalized industries. It’s all so-called privatized but owned by either the Islamic Guards or by the Mullahs and their sons and daughters.

Talia Baroncelli

If I could just ask you one last question on this because I think it’s really important. We saw protests in Iran— Women, Life, Freedom! There were lots of protests in Iran in September 2022 and then after that. A lot of people argue that the protests didn’t build enough momentum to make a change or overthrow the government because there was no large worker strike or there was no general strike that could actually pose a threat to the government. That’s assuming that they actually want to change the government. I don’t want to get into that conversation; that’s perhaps for another time.

On the topic of unions, do you think the government continues to not support unions because it perhaps knows that it would pose such a huge threat to its continued power and to the power of the Revolutionary Guard and the Islamic Republic in general? If there was this unionization that was to take hold and have some sort of momentum, it would perhaps pose a large threat to the consolidation of power of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Saeed Rahnema

Absolutely. Absolutely. The Islamic regime is not only not allowed to have any unions; even the Islamic councils that were formed after we were expelled, most of these councils became Islamic councils. Even these yellow state-controlled councils were not allowed in large industries. They said that later, we’ll do it. It’s 44 years now. They haven’t done it. We have so many labor activists who are imprisoned now. It’s good that we are discussing this on May 1 today. Many of our activists are in jail now. There have been lots of efforts to create these unions. In terms of what you mentioned, why Woman, Life, Freedom! declined, although it’s still alive, I argued that street demonstrations alone cannot topple this regime. In order to do that, we need a quadripartite.

I’ve written an article on this. A quadripartite alliance of the street, educational systems, workplaces, and also businesses. If we have linkages between all of these things, then we would be able to topple this regime, which is so difficult to do. Of course, one of the main reasons that it cannot be done is because of the brutal suppression of any movement that continues. In order to do that, we need to have these quadripartite alliances.

Talia Baroncelli

Dr. Saeed Rahnema, it’s been really great speaking to you.

Saeed Rahnema

Thank you, Talia. Thanks so much for having me. I appreciate that.

Talia Baroncelli

Thank you for watching theAnalysis.news. You can find us online at theAnalysis.news. See you next time.

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Dr. Saeed Rahnema is an award-winning Professor of Political Science and Public Policy at York University. He was the founding director of York’s School of Public Policy and Administration. In his homeland, Iran, he taught and worked as a member of the executive of the Industrial Management Institute in Tehran. He has also served as an officer of the UNDP, as a director of the Middle East Economic Association (MEEA), and as a member of the editorial boards of several journals. He is a frequent commentator on Canadian and international media on the issues of the Middle East and Islam. He is the author of several books and numerous articles in English and Persian on topics such as religious fundamentalism, secularism, left and labor movement, diaspora, and multiculturalism.

Honest Government Ad | Visit Tasmania! 🇦🇺